MOST READ

- Bandcamp ──バンドキャンプがAI音楽を禁止、人間のアーティストを優先

- interview with Sleaford Mods 「ムカついているのは君だけじゃないんだよ、ダーリン」 | スリーフォード・モッズ、インタヴュー

- Columns Introduction to P-VINE CLASSICS 50

- 別冊ele-king 坂本慎太郎の世界

- DADDY G(MASSIVE ATTACK) & DON LETTS ——パンキー・レゲエ・パーティのレジェンド、ドン・レッツとマッシヴ・アタックのダディ・Gが揃って来日ツアー

- Daniel Lopatin ──映画『マーティ・シュプリーム 世界をつかめ』のサウンドトラック、日本盤がリリース

- Ken Ishii ──74分きっかりのライヴDJ公演シリーズが始動、第一回出演はケン・イシイ

- DJ Python and Physical Therapy ──〈C.E〉からDJパイソンとフィジカル・セラピーによるB2B音源が登場

- Autechre ──オウテカの来日公演が決定、2026年2月に東京と大阪にて

- Masaaki Hara × Koji Murai ──原雅明×村井康司による老舗ジャズ喫茶「いーぐる」での『アンビエント/ジャズ』刊行記念イヴェント、第2回が開催

- interview with bar italia バー・イタリア、最新作の背景と来日公演への意気込みを語る

- aus - Eau | アウス

- 見汐麻衣 - Turn Around | Mai Mishio

- ポピュラー文化がラディカルな思想と出会うとき──マーク・フィッシャーとイギリス現代思想入門

- 橋元優歩

- Geese - Getting Killed | ギース

- Ikonika - SAD | アイコニカ

- interview with Ami Taf Ra 非西洋へと広がるスピリチュアル・ジャズ | アミ・タフ・ラ、インタヴュー

- interview with Kneecap (Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap) パーティも政治も生きるのに必要不可欠 | ニーキャップ、インタヴュー

- Dual Experience in Ambient / Jazz ──『アンビエント/ジャズ』から広がるリスニング・シリーズが野口晴哉記念音楽室にてスタート

Home > Interviews > interview with Still House Plants - 驚異的なサウンドで魅了する

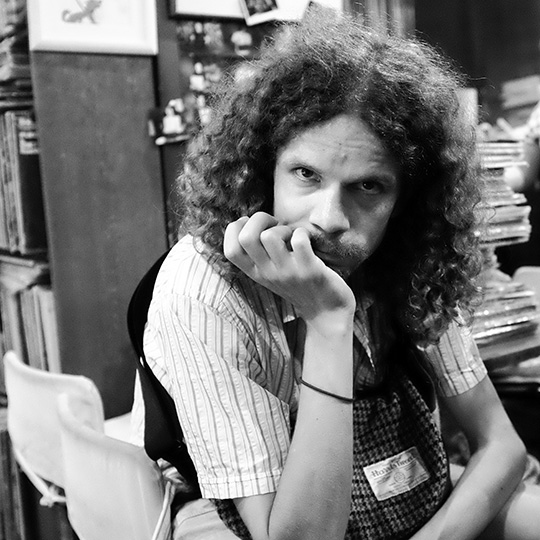

interview with Still House Plants

驚異的なサウンドで魅了する

——スティル・ハウス・プランツ、来日直前インタヴュー

by James Hadfield

Towards the end of a conversation with Still House Plants, vocalist Jess Hickie-Kallenbach speaks of being “turned inside-out” in the course of playing together with her bandmates, guitarist Finlay Clark and drummer David Kennedy. She’s talking about how she developed her inimitable style – deep-voiced, raw, disarmingly emotive – but she could equally be describing the band’s radical deconstruction of the art of song.

Working with a minimal set-up of guitar, drums and voice, the London-based trio make music that is in a constant state of becoming. On their 2020 album, “Fast Edit,” they incorporated lo-fi phone memos and rehearsal tapes alongside studio recordings, giving the sense of hearing the songs at various stages in their creation. Follow-up “If I don’t make it, I love u,” released earlier this year, is more languid, foregrounding the slowcore influences that were evident on the group’s 2016 self-titled debut EP. Yet it’s still thrillingly unpredictable, full of songs that come unspooled and snap taut with a logic entirely unto themselves.

Clark, Hickie-Kallenbach and Kennedy first met as students at Glasgow School of Art in 2013, and their early recordings were released on Glasgow cassette label GLARC. A 2016 gig at London’s Cafe Oto caught the ears of the venue’s archivist, Abby Thomas, who started the bison label in order to release their music. The venue would become a crucial supporter, inviting the band to curate a three-day residency in 2019 and letting them use its temporary Project Space studio to rehearse and work on new material. (When she isn’t touring, Hickie-Kallenbach can be found working behind the bar at Cafe Oto.)

For their debut Japan show, Still House Plants will be sharing a bill with goat, which makes sense: both groups use nominally rock instrumentation but are deeply informed by the methods and logic of electronic music. In a 2020 interview with Tone Glow, Hickie-Kallenbach said her earliest memories of making music were producing “really bad drum ‘n’ bass” tracks on computer with her dad at the age of six or seven, and Still House Plants create and re-arrange songs with a cut-and-paste approach that will be familiar to anyone who’s messed around with DAW software.

Speaking via Zoom, the three members show the same rapport that’s on display during their live performances. Nobody dominates the conversation: they listen carefully to each other, often picking up on what someone else has said. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I was hoping to ask about Cafe Oto, since people reading this might not be familiar with the venue, but it's played quite a significant part in the band's history. How would you describe it to somebody who's not been there before?

Jess Hickie-Kallenbach: It's a small-sized venue that has very varied programming. I guess historically, maybe, it was more free jazz. Now, it's broadened out to any kind of experimental music, from band stuff to noise, more performative things. Our introduction to the place was in 2019, I guess, when they were working with Jerwood [Foundation] – a sort of funding body to help out young artists – and they nominated us. That was where we first encountered it, properly, as a venue.

David Kennedy: I suppose we'd played there before.

JHK: Yeah, we'd played there once, I think, at that point. Maybe twice. But I think it felt a bit more disconnected – it just felt like a venue. And then after that, it was like: Oh, right, they actually want to support young... well, not necessarily young, but new acts.

DK: I feel there was a bit of a push, at one point, to try and kind of shake off the cobwebs (laughs), of being this sort of free jazz space or experimental music space – but who defines what that is?

JHK: That's exactly it. I think the definition of what that is – of what experimental music, or whatever odd music, is – had to change. And [it's] not one person [who] decides what that means.

Finlay Clark: I was just going to say, I have very warm feelings towards [Cafe Oto], because they were just so supportive when we were starting out. We've played at quite a few venues now, and it just amazes me how they put it together, year after year. And delicious food, and tea! Sake and stuff…

In my experience of going to Oto, I've felt like the audience there is very engaged. Do you find playing somewhere like that, compared to at a festival or something, changes things for you in the course of the performance?

JHK: We recently played at a festival in the UK [End of the Road], which was like a camping festival. We've played at festivals before, in cities, but this was like a proper British, wellies-and-babies sort of festival. It still felt like people were paying attention. I don't know if we're just lucky, that we find places where people actually really want to listen, or engage.

DK: We were doing this support tour with Tirzah, and we were playing at this venue in London called Brixton Electric. I think it was like 2,000 people-ish, in this big, quite raised stage, and I remember thinking, "Oh, I don't know how it's going to translate in that sort of setting…” But I remember afterwards, I really got the feeling that it worked, and we didn't have to change anything – which sort of tells me that we could literally play anywhere (laughs).

JHK: Yeah, we don't need much. We kind of need to stand close together, and we need to keep everything feeling kind of simple. But that can literally happen anywhere, you know? It's quite a fortifying feeling.

Sorry, Fin, were you going to add something there?

FC: Yeah, I was going to say, the difference between a festival and Oto – in a way, not much. I don't really look out at the audience much. I'm kind of just listening to Jess and David, and just locked in, and what's happening to the right of me – which is normally where the audience is – it doesn't change [things].

DK (grimacing): Uh. Oh my God…

Are you okay there?

DK: Yeah, I need to replace my pillows, because my neck is in pain.

FC: Oh, you should get – what are they? I've got one of these... It's not memory foam, but it's got a panda [logo] on it.

DK: Oh, I've seen those.

FC: Yeah, they're really, really good.

JHK: Pillow talk, yeah? I go for super-thin. Super, super thin. Basically nothing.

FC: I used to do that, and now I'm all into neck support.

JHK: But it feels like it does worse to have your neck up high. I dunno, whatever. I was gonna say, obviously it's really nice to do a proper sound check. That's the thing that really changes everything. But I think we're pretty good at doing it all. It's obviously not fun if things are going wrong, like if the sound isn't quite right. But also, there's something about the way that we're set up, which means that we're kind of constantly supporting each other. I guess that's the good thing about being set up as a triangle.

Your music feels very open-ended, but then I guess there are start points and end points, and there are constraints, right? It's not just completely malleable.

DK: A lot of the songs, I feel, have become quite structured. Not all of them, but with a lot of them, I know exactly what I'm going to play all the time.

Do you ever feel any sort of desire to push back against that?

DK: I think I do. I suppose we do try to account for that as well, of wanting to change things up. Usually, that often happens before [the performance]. We discuss, like, “This set, we're cutting it in half, and moving the second half to the top, or maybe we'll change what songs we go into.” So it'll be, like, working on transitions and stuff.

JHK: There's something interesting that happens, when we actually record songs, after playing and working on them for a long time. I think that's when they get really cemented. I think that right now, playing quite a lot of songs from the record [“If I don’t make it, I love u”] means that we really do know the edges of things, and the boundaries of the songs. The way that they change, for us, is more like mood and stuff like that, but also what they sit next to: transitioning from one song to another, finding ways to do that. That feels interesting to us. We like a set to have a sort of flow, almost like a DJ set or something – songs blurring into each other. So that's how songs change, I guess, as we tour them. But I think, as the voice, I have a very different time to DK [David]. I can kind of do what I want much more easily. There's a consistency to what I do, but also there's room for different kinds of expressing.

FC: Yeah, I totally hear what you're saying. Having a drum part that's pretty solid gives you a ground to kind of free-form, sometimes, over the top. Also, I think there's freedom in structure. I remember I saw Ian McKellen do a monologue, and he was talking about how when you know your lines so well, you can deliver them in a really natural way. When you know your parts really well – at least for me – I find that you can kind of give the impression that you're making it up. I think there's a freedom to knowing exactly what you're doing, because it gives the impression of spontaneity.

JHK: It's funny that thing, because I feel like the presumption about our music is that everyone assumes that it's at this particular level of improvised. Obviously, there's fluctuations – there's things that change – but people are like, "Woah, that's basically 100% improvised" as they hear it. And I wonder what that is about it. Maybe it's convenient for it to be imagined as entirely improvised, because it's jerky and has strange changes. But to me, it feels so tight, having these – essentially – drops (laughs) and stuff like that. In a way, it's like: How could that be improvised? But yeah, I think it's all kind of true at the same time. We know what we're gonna do. We know that there's going to be some kind of fluctuations. We practise the starts and ends of songs, and the transitions, and we work those all out, and we make this sort of monolith of a song that is a set (laughs).

DK: I thought that was a good point you made, Jess. When stuff is being recorded, things start to feel fully formed. I do feel like there is an element of sort of firming up the songs through playing them live, especially the newer ones. We've even had points where we played a song a certain way, and then we'd be like, "Oh, I didn't really like how that went." And all of a sudden, the next set we do it, it would have a different drum part and be connected to the end of another song, or something like that. So there is an element of – especially with newer stuff – that it forms and forms and forms through playing live.

JHK: Yeah, I think so. It might not be that the whole structure of a song changes, but we chop things up and we just stick them next to something else, and that becomes the new song. We're writing now, and we're playing some new things. They're changing, they're still solidifying, so they're probably going to change across the tour.

FC: It's definitely a good way to test out material, on stage. I've always felt that you kind of know when something works or not, quite instinctively.

Do you think that those instincts have improved over the years of doing the band?

FC: I think... it's an annoying answer, but sort of yes and no. I've learnt to listen to and trust my judgment, artistically. It takes a long time, to really be able to listen to yourself and trust your instincts. I do question things a lot more, as well. I found when I was in my early 20s, I had more confidence and sort of naivety at the same time, and that's kind of transformed into being more cautious, but also being able to listen to myself and know my instincts better. So it's kind of a bit of both, for me.

JHK: I feel the opposite. I've become less confident and more annoying. Joking.

DK: It's funny thinking about instinct, isn't it? At least in terms of songwriting stuff. I wonder how much of that comes from just growing. I'm trying to think if there's a link, as well, to just actually getting more comfortable with an instrument.

JHK: Yeah, like, it's taken you a long time. When we started making music, David hadn't played drums in a while. I guess it was probably the same for all of us. In a way, we were learning how to play with each other, which actually meant we played very differently. Obviously, Fin, you'd played guitar and you knew the instrument, but you were working out a new way of playing, and that was in response to both of us. That stuff takes a really, really long time.

DK: Yeah, it's probably only in the last year and a half, I've realised that I actually really enjoy playing drums.

FC: I've also been thinking, because you practise drums a lot – I don't practise the guitar. I sit at home and practise the piano a lot, and that's kind of where my practice goes, but guitar... I think that I don't like how guitar sounds, when it's too good (laughs). Is it Robert Fripp, is that his name? Very perfectly technical. That's not for me. I like it being a bit loose. In a way, I'm intentionally not practising it.

JHK: You play a lot, though, Fin. That's the opposite of what you said about the Ian McKellen lines! And you do play a lot, because we play a lot.

FC: What I mean is, like, I don't practise scales.

JHK: You don't need to.

FC: It's more like learning the part – the set – in reference to learning lines, the Ian McKellen lines, and practising the instrument is separate. And yeah, just thinking about Keith Richards, basically, playing copiously. I think they're separate things.

DK: I used to have a similar thing with drums. I was like: Oh, I hate drums, I hate drum culture. There's a real minefield, as well, in just how you can play drums. I can't be arsed with people doing fills, and all this sort of stuff. There's a point where I was like: If I start practising all the time, am I just going to become one of those drummers? But then there's a certain point where you're like: I have enough personality, I'm a real person who's taken a break from an instrument and come back to it as a more fully formed human. I trust in my own instincts, that I'll be able to actually engage with this instrument and practise it, and be able to actually make it good (laughs).

Jess, how has your relationship with your instrument – your voice – changed? Obviously you're singing a lot lower than you did when the band first started...

JHK: I was really lucky, I guess, because I didn't sing before we started making music. I'd always wanted to, but I wasn't very confident – I guess my voice felt really small. It happened pretty fast, but everything sort of aligned at the right moment for me, where we started making stuff, and I also started really finding my own voice as a person… It feels like the more we were playing, the more I would just be – without sounding crazy – kind of turned inside-out. I was just more able to wear what I was feeling, and that meant that my voice changed. I think it was confidence, basically.

DK: Yeah, that's a big thing.

JHK: And to be vulnerable. Big time.

取材・序文:ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド(2024年9月11日)

| 12 |

Profile

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド/James Hadfield

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド/James Hadfieldイギリス生まれ。2002年から日本在住。おもに日本の音楽と映画について書いている。『The Japan Times』、『The Wire』のレギュラー執筆者。

James Hadfield is originally from the U.K., but has been living in Japan since 2002. He writes mainly about Japanese music and cinema, and is a regular contributor to The Japan Times and The Wire (UK).

INTERVIEWS

- interview with Sleaford Mods - 「ムカついているのは君だけじゃないんだよ、ダーリン」 ——痛快な新作を出したスリーフォード・モッズ、ロング・インタヴュー

- interview with bar italia - バー・イタリア、最新作の背景と来日公演への意気込みを語る

- interview with Kneecap (Mo Chara and Móglaí Bap) - パーティも政治も生きるのに必要不可欠 ──ニーキャップ、来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Chip Wickham - スピリチュアル・ジャズはこうして更新されていく ――チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with NIIA - 今宵は、“ジャンル横断”ジャズ・シンガーをどうぞ ──ナイア、インタヴュー

- interview with LIG (Osamu Sato + Tomohiko Gondo) - 至福のトリップ体験 ──LIG(佐藤理+ゴンドウトモヒコ)、インタヴュー

- interview with Kensho Omori - 大森健生監督、『Ryuichi Sakamoto: Diaries』を語る

- interview with Lucrecia Dalt - 極上のラテン幻想奇歌集 ——ルクレシア・ダルト、インタヴュー

- interview with Ami Taf Ra - 非西洋へと広がるスピリチュアル・ジャズ ──アミ・タフ・ラ、インタヴュー

- interview with Jacques Greene & Nosaj Thing (Verses GT) - ヴァーシーズGT──ジャック・グリーンとノサッジ・シングが組んだ話題のプロジェクト

- interview with Kassa Overall - ヒップホップをジャズでカヴァーする ──カッサ・オーヴァーオール、インタヴュー

- interview with Mat Schulz & Gosia Płysa - 実験音楽とエレクトロニック・ミュージックの祭典、創始者たちがその歴史と〈Unsound Osaka〉への思いを語る

- interview with Colin Newman/Malka Spigel - 夏休み特別企画 コリン・ニューマンとマルカ・シュピーゲル、過去と現在を語る

- interview with Meitei - 温泉をテーマにアンビエントをつくる ──冥丁、最新作を語る

- interview with The Cosmic Tones Research Trio - アンビエントな、瞑想的ジャズはいかがでしょう ——ザ・コズミック・トーンズ・リサーチ・トリオ

- interview with Louis and Ozzy Osbourne - 追悼:特別掲載「オジー・オズボーン、テクノを語る」

- interview with LEO - 箏とエレクトロニック・ミュージックを融合する ――LEO、インタヴュー

- interview for 『Eno』 (by Gary Hustwit) - ブライアン・イーノのドキュメンタリー映画『Eno』を制作した監督へのインタヴュー

- interview with GoGo Penguin - ジャズの枠組みに収まらない3人組、これまでのイメージを覆す最新作 ――ゴーゴー・ペンギン、インタヴュー

- interview with Rafael Toral - いま、美しさを取り戻すとき ——ラファエル・トラル、来日直前インタヴュー

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE