MOST READ

- The Jesus And Mary Chain - Glasgow Eyes | ジーザス・アンド・メリー・チェイン

- Free Soul ──コンピ・シリーズ30周年を記念し30種類のTシャツが発売

- interview with Keiji Haino 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回

- Beyoncé - Cowboy Carter | ビヨンセ

- CAN ——お次はバンドの後期、1977年のライヴをパッケージ!

- Columns ♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く

- interview with Keiji Haino 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第1回 | 「エレクトリック・ピュアランドと水谷孝」そして「ダムハウス」について

- interview with Toru Hashimoto 選曲家人生30年、山あり谷ありの来し方を振り返る | ──橋本徹、インタヴュー

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- 壊れかけのテープレコーダーズ - 楽園から遠く離れて | HALF-BROKEN TAPERECORDS

- Jlin - Akoma | ジェイリン

- 『成功したオタク』 -

- まだ名前のない、日本のポスト・クラウド・ラップの現在地 -

- interview with Mount Kimbie ロック・バンドになったマウント・キンビーが踏み出す新たな一歩

- exclusive JEFF MILLS ✖︎ JUN TOGAWA 「スパイラルというものに僕は関心があるんです。地球が回っているように、太陽系も回っているし、銀河系も回っているし……」 | 対談:ジェフ・ミルズ × 戸川純「THE TRIP -Enter The Black Hole- 」

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Bingo Fury - Bats Feet For A Widow | ビンゴ・フューリー

- みんなのきもち ――アンビエントに特化したデイタイム・レイヴ〈Sommer Edition Vol.3〉が年始に開催

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- Beyoncé - Renaissance

Home > Columns > 階級、政治、スリーフォード・モッズとアイドルズ

昨年、このサイトの記事で、音楽における政治の重要性について書いた。アーティストがオーディエンスの生活と繋がりを持ち、自分たちの音楽と世界への視点を豊かにする方法と、メインストリームな組織以外の場所で、繋がりを築く方法について述べた。しかしその記事では取り上げなかったひとつの大きなイシュー(問題点)がある。政治に内在する対立が芸術に入り込んだ時に何が起こるのか、ということだ。

これこそが、多くの人が日常的な交流のなかで、政治の話を避けようとする主な理由だ。新しい同僚に対して慎重になって政治についての話題を避けたり、高校時代の旧友が、政敵について好意的に語ると胃が締めつけられる気がしたり、何杯かの酒の後に抑制が効かずに家族と衝突してしまったりする。学校の教師をしている両親の息子である自分は、普段、ミュージシャン、ライター、アーティストやその他のクリエイティヴな人びとの輪のなかでほとんどの時間を過ごしているが、自分の政治観(社会的リベラル、経済的には左寄り)が決して皆のデフォルトではないことを想像するのが難しい時がある。だが、自分の住む国やより広い世界に少しでも目を向けると、それが真実ではないことがわかる。

音楽の世界にも充分すぎるほどの対立があり、ミュージシャンが自分の意見をオープンにすればするほど、その境界線が明確になる。セックス・ピストルズとPiLのジョン・ライドンは、昨年の米国大統領選挙でトランプ支持を表明した。ザ・ストーン・ローゼズのイアン・ブラウンは、COVID-19の偏執的な陰謀論の声高な擁護者となり、アリエル・ピンクとジョン・マウスは米連邦議会を襲撃したトランプ支持者たちとともに行進し、モリッシーは口を開くたびに、人種差別的なばかげた言葉の塊を吐き出し続けている。彼らは何をしているのだろう? 彼らは我々の仲間ではなかったのか? どうやら“我々”にはあらゆる大衆が含まれているらしい。

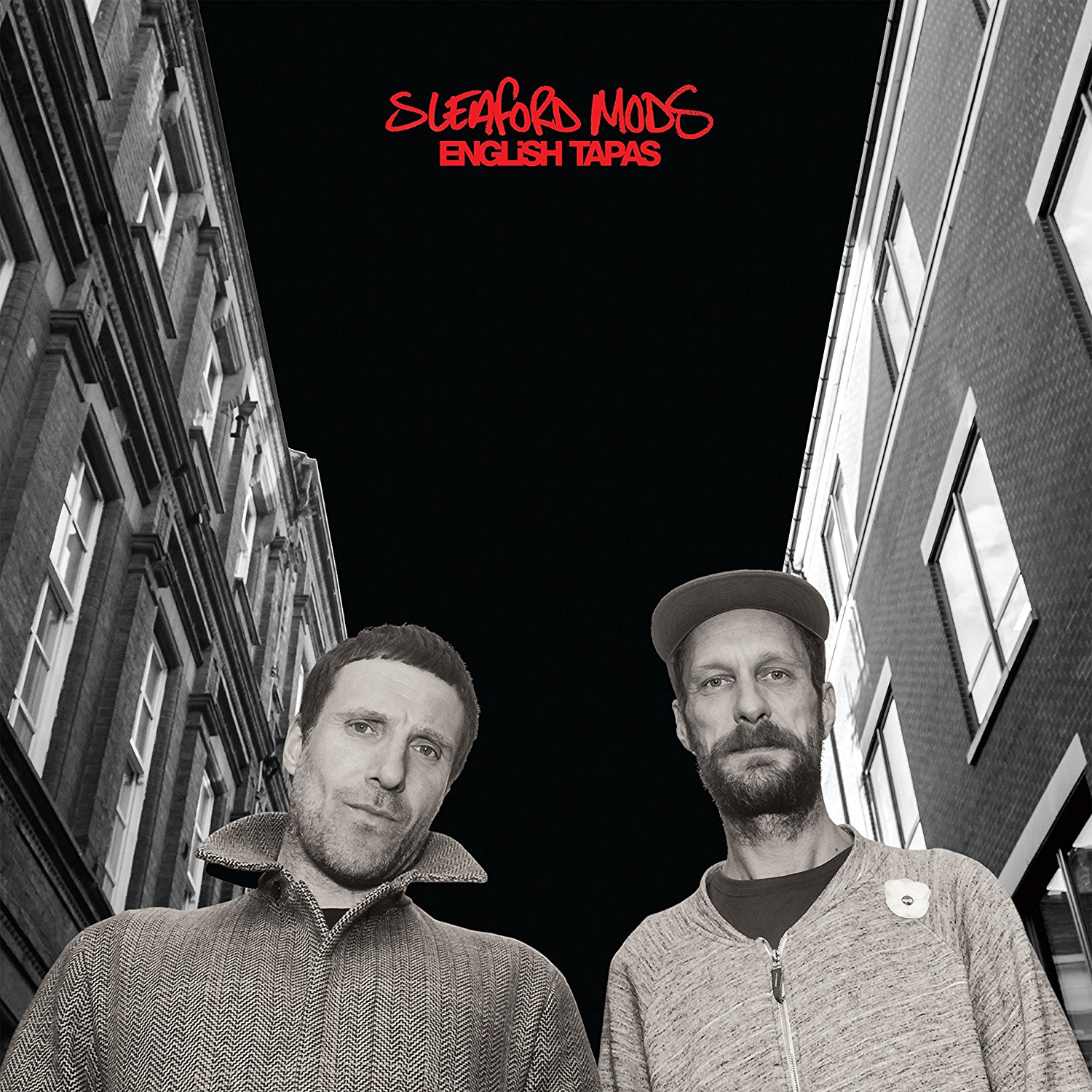

一見、似たような政治観を持つ人びとの間でも、より微妙な対立が生じることがある。英国のグループ、スリーフォード・モッズとアイドルズは表面上、非常によく似ている。どちらも政治意識が高く、イギリスの保守党体制を鋭いリリックで批判し、音楽的にはまったく異なる方法で、ポスト・パンクのねじ曲がって歪んだ構造を想起させる。しかし、彼らの間には、階級政治に根差した意見の相違があったのだ。

2019年、スリーフォード・モッズのジェイソン・ウィリアムソンが、アイドルズは、はるかに安定したミドル・クラス(中流階級)出身であるにもかかわらず、「ワーキング・クラス(労働者階級)の声を盗用している」と批判した。このコメントで引かれた、スリーフォード・モッズとアイドルズの間の境界線は、新しいものではない。1981年にドイツのSPEX誌がザ・フォールのマーク・E.スミスに、ギャング・オブ・フォーについて訊ねた際のスミスの批判は、似たような所から来ていたのだ。

「彼らは左翼的な思想を説く。彼らは大学で学び、特権階級に属している。ワーキングクラスが何を求めているのか、知ったふりをしているのが問題だ。でも何もわかっていない。シャム69は、自分たちが言っていることをよく理解していてよかった。自分を含むイギリスのワーキングクラスにとって、ギャング・オブ・フォーの音楽は、侮辱的で、無礼で傷つけられると言う意味で有害だ」

ここには、階級政治に関わるイシューがあり(2017年のジョーダン・ピールの映画『ゲット・アウト』でも人種問題における力学の似たような試みが行われている)、ブルジョワのリベラル派が自分自身のブランド価値を高めるためにワーキングクラスを装って、もがいてみせることがある。その方法で迎える典型的な結末は、ワーキング・クラスの人たちが元の場所に置き去りされ、彼らの声さえもが他人に利用され、薄められてしまうのが常だ。スリーフォード・モッズの最近のアルバム『Spare Ribs』からの曲、「Nudge It」で、ウィリアムソンは、こう言う。

もう少し根本的なところでは、いつの時代も説教臭い人間は忌々しいし、リベラルや左派の人間が他人の意見に対して小うるさく、偉そうにする傾向があることが、ジョン・ライドンを、トランプの、ガサガサした革のような腕の中に押し込めた原因のひとつかもしれない。そもそもパンクは、進歩的な政治のムーヴメントとはいえないものだった。パンクは常に何かに反応していたが、反応と反動の境界線は、我々の多くが信じたかったものよりも、薄っぺらなものだったのだ。1970年代後半、パンクはしばしば保守の体制に反応したが、根本的には、世間体のよい立派な人間になるように命令する、あらゆる声に反発していたのだ。

そういう意味でトランプは、良いパンクな大統領だった。彼の魅力の多くは、結果など気にもとめずに、人を混乱させ、無視し、奪ったり侮辱したりしながら人生を歩む能力にある。トランプの不名誉な行いを見ると、パンクが与えたのと同じような、責任感からの解放がある。彼は立派であろうとせず、繊細さや礼儀正しさが求められるところで失敗しても、無頓着でいられる才能があるのだ。話す内容の細部は意味をなさないが、彼が発するメッセージはキャッチ―でシンプル、そしてパンク・ロックのコーラスのように、反復的だ。

トランプと極右の人びとのシンプリシティを志向する本能こそが、ブルース・スプリングスティーン(“ボーン・イン・ザ・USA”)やニール・ヤング(“ロッキン・イン・ザ・フリー・ワールド”)、レイジ・アゲインスト・ザ・マシーン(“キリング・イン・ザ・ネーム”)などの反国家主義的な曲を、国家主義的な主義信条のサウンドトラックとしてうまく利用できた理由だ。彼らはバカではない。これらの曲が彼らに反対するものであることを知りながら、その繊細なメッセージを一切見ようとはせずにそれを消し去り、完璧な重度の繰り返しにより、自分たちのための曲だと主張することができた。曲のキャッチ―さを利用し、皮肉を逆手にとり、洗練された部分にはドリルで穴をあけて、曲が元来持つシンプルな魅力を掘り起こしたのだ。トランプの「クソッタレ、お前のいうことなんて聞かない」という態度こそが、彼の支持者たちへのアピールの核心だ。

スリーフォード・モッズは、そのような伝統のなかにおいては、それほど派手な不作法さはない。ウィリアムソンは音楽が生まれた場所について正直であることを重視し、演壇やお立ち台などがなくても人びとにコミュニケートする能力がある。“Elocution”という楽曲は、皮肉たっぷりの歌詞で始まる。

この歌詞は、アイドルズや他のミドル・クラスのロッカーたちへの批判のようにも読めるが、バンドが成功するにつれ、より大きな会場に招かれ、ウィリアムソン自身が隣人たちのことを書いて有名になった地元の街から、家族を連れて郊外に引っ越すにつれ、自分のなかで芽生えた不安が反映されているのかもしれない。歌詞の皮肉はさておき、スリーフォード・モッズはパンデミックで大打撃を受けた、インディペンデント系の会場の強力な支援者であり、2020年12月には、“インディペンデント・ヴェニュー・ウィーク・キャンペーン”を支持してコンピレーション・アルバムに曲を提供している。

アイドルズもまた、インディペンデント系の会場の積極的な支援者であり、2021年に発表した楽曲“Carcinogenic”のミュージック・ヴィデオは、彼らの故郷ブリストルの地元の会場を支援するために制作された。バンドとPR会社は、確かにそれを大々的に宣伝しているが、ブリストルにある会場のうち、文句を言っている所などあるだろうか?

ある意味、アイドルズのヴォーカルのジョー・タルボットは、ウィリアムソンとは異なる領域に、自分の真正性の杭を打ち込んでいるともいえる。彼のリリックや公式見解の多くは、ソーシャルメディアなどの不安定な場でよくみられる、告白めいた、少し防御的な姿勢で書かれてはいるが、ある種のポジティヴな自己表現を土台としている。彼には(ワーキング・クラスとしての)“真正な”生い立ちの物語はないかもしれないが、自分に対して正直だ。2020年のアイドルズのアルバム『ウルトラ・モノ』に収録されている“The Lover”では、まさにこのような声で、批評する人たちに訴える。

社会の変化に伴い、ワーキング・クラスとミドル・クラスの伝統的な区分が複雑になっているのも問題のひとつだろう。アイドルズ自身はワーキングクラスではないかもしれないが、彼らの音楽の怒りと祝福の声は、増え続ける不安定雇用に陥っている、大学教育を受けた社会的意識が高い若者層と呼応している。最近出現したプレカリアート(雇用不安定層)の新メンバーたちは、その苦悩や先の見えない将来の不安を味わっているにもかかわらず、気取ったノスタルジックな1950年代の田舎やワーキング・クラスの生活の幻想を懐かしむ政治やメディアから、特権的な学生と嘲笑されているのだ。彼らは、田舎は自分たちの世界よりも現実的だといわれたり、ビスケットの缶の絵からそのまま取ってきたような田舎の愛国心のイメージなどに、また、自分たちの理想主義が揶揄され、軽蔑されることに疲れている。多くの人にとってアイドルズのヴォーカリスト、ジョー・タルボットは、“本当のイングランド”という安直な概念を切り崩し、フラストレーションや怒りを受け止めてくれる存在なのだ。

「不平等ということに怒っているのなら、“お前は間違っている、クソッタレ”というのではなく、代替案としての平等を説くべきだ」と、タルボットはウィリアムソンの批判に応えて述べた。「1970年代にパンクスがやっていたことをいまも議論し続けているのは、“クソッタレ”的なことでは成功しなかったという事実があるからだ」

「もうウンザリだ、俺の怒りは正当化される!」というアチチュード(姿勢)もあり、トランプ支持者のそれと似ているようにも聞こえるが、極端な比較をするのには慎重になる必要がある。似たような怒りのアクティヴィズム(行動主義)であっても、残酷ではない社会を求めて戦うことと、白人至上主義を支持して議会を襲撃することは同義ではない。だが、その原動力には似通ったものがある。どちらも怒りを原動力とするマシーンであり(“怒りはエネルギーだ”と言ったのは誰だっけ?)、いずれも無力感やある程度の個人的な承認欲求から生まれたものだ。彼らは信じられないぐらい複雑化する社会に方向性を与えると同時に、人びとの声を多数に分けて、それぞれに自分の主張を最も声高に叫ばせている。

アイドルズは、多くの政治的な議論やレトリックには軋轢が存在することを認識しているようだが、団結を求める彼らの声(少なくとも彼ら側では)は、自分自身の真実を語るというタルボットの、本質的には個人主義的な必要性に、常に磨きをかけている。“Grounds”という曲のなかで、彼は批判者たちが建設的ではないと非難する。

タルボットにしてみれば、自分の人種や階級を理由に、自分が関心のあるイシューに貢献することを妨げられたくはないのだ。しかし他人は、タルボットのその思いには、白人のミドル・クラスの男性として、自分が選択したどの領域の誰の問題にも関わって指揮を執ることができるという、生まれながらの特権があると思っていると感じてしまう。さらにその結果として得られるキャリア上の利益の権利があると思っている、そのことこそが問題の核心なのだ。

このような論争を、大きな視点から眺めてみれば、それほど重要なことではない── 「音楽は政治問題を解決できない」と言ったジェイソン・ウィリアムソンはおそらく正しいし、その延長線上にあるミュージシャン同士の政治的な不和はさほど重要ではない。しかし、音楽における政治の役割が、アーティストがいかに自分たちのオーディエンスにつながるかということに行きつくのだとすれば、スリーフォード・モッズとアイドルズは微妙に異なりながらも、かなりの程度、重なり合うオーディエンスに対して、非常に効果を発揮している── 一方は政治を辛辣でシュールな、時に自嘲的な日常の見解と織り交ぜ、他方は、あらゆる自制心を焼き尽くす、自分自身と信念に対する祝福のような主張をしているのである。

Class, Politics, Sleaford Mods and Idles

by Ian F. Martin

In an article for this site last year, I talked about the importance of politics in music — as a way for artists to connect with their audience’s lives, of enriching both their music and perspective on the world, and to build links with others organising outside the mainstream. One big issue that piece didn’t try to address, though, was what happens when the conflict inherent in politics enters art.

This, of course, is the reason many people try to avoid politics in their daily interactions — why we tiptoe around it with new coworkers, why we feel our stomachs tighten when an old high school friend drops a talking point favoured by our political enemies into the conversation, why we clash with family members after a few drinks have loosened our inhibitions. For me, the son of schoolteachers, who spends most of his time in a bubble of musicians, writers, artists and other creative people, it’s sometimes hard to imagine that my politics (socially liberal, economically left-leaning) aren’t the default for everyone, but a simple glance around the country I live in or the wider world proves that’s not true.

Within the music world, there’s plenty of division too, the lines of which become clearer the more open musicians are about their views. John Lydon of The Sex Pistols and PiL came out in support of Donald Trump during last year’s US elections; Ian Brown of The Stone Roses has been a vocal proponent of paranoid COVID-19 conspiracy theories; Ariel Pink and John Maus marched with the Trump supporters who invaded the US Senate in January; nuggets of racist idiocy continue to drop out of Morrissey’s mouth every time he opens it. What are they doing? Weren’t they one of us? Apparently “us” includes multitudes.

Even among people with apparently similar political outlooks, more subtle antagonisms can arise. The British groups Sleaford Mods and Idles are on the face of it quite similar — both delivering politically conscious, sharply worded lyrics critical of the British Conservative establishment, with music that evokes, albeit in very different ways, the twisted and distorted structures of post-punk. Nevertheless, they’ve had their disagreements, with the roots lying in class politics.

In 2019, Jason Williamson of Sleaford Mods criticised Idles for “appropriated a working class voice” despite coming from a far comfortable, middle-class background. The line these comments draw between Sleaford Mods and Idles isn’t a new one. Back in 1981, when German magazine SPEX asked Mark E. Smith from The Fall about Gang of Four, Smith’s criticisms came from a similar place:

“They preach the leftist ideas. They went to university and belong to the privileged class. The problem is that they pretend to know what the working class wants. But they haven't got a clue. Sham 69 knew what they were talking about and they were good. The English working class (including myself) find the music of the Gang of Four offensive, insulting, hurtful.”

There’s an issue relating to class politics here (and Jordan Peele’s 2017 movie “Get Out” takes aim at a similar dynamic in race issues) in how bourgeois liberals often dress themselves up in the struggles of the working classes to boost their own personal brands, in a way that typically ends up leaving the working classes right where they were, with even their own voice appropriated (and often watered down) by others. On “Nudge It” from Sleaford Mods’ recent album “Spare Ribs”, Williams says:

“I been out playin to this mindless abandon / This ropey idea about love and connection / Just stuck on silly ideas / ‘Cause it's all you can cook / You fucking class tourist / You mix your social groups up”

On a more fundamental level, of course, people who come across as preachy are always annoying, and the tendency of liberals and the left to be fussy and pompous about other people’s opinions seems to be part of what pushed John Lydon into the leathery arms of Trump. But then punk was arguably never a politically progressive movement to begin with: it was always reacting against something, and the line between reactive and reactionary is perhaps thinner than a lot of us want to believe. In the late-1970s, it was often reacting against a conservative establishment, but more fundamentally, it was reacting against any voices ordering them to be respectable.

Trump was a good punk president. A lot of his appeal lies in his ability to shuffle, shrug, mug and insult his way through life with no care for the consequences. There’s a liberation from responsibility in watching Trump’s disgracefulness that is similar to what punk gives — he doesn’t care about being respectable and he has a talent for blundering carelessly through any demands for subtlety or decorum. When he speaks, the details are always nonsensical, but the message is as catchy, simple and repetitive as a punk rock chorus.

It’s an instinct for simplicity that has enabled him and other far right figures to successfully co-opt anti-nationalistic songs by Bruce Springsteen (“Born in the USA”), Neil Young (“Rockin' in the Free World”) and Rage Against The Machine (“Killing in the Name”) to soundtrack a nationalist cause. They’re not stupid: they know these songs are aimed against them, but by simply refusing to see the subtlety in the message, they can erase it and claim the song for themselves through sheer weight of repetition, using the catchiness of the hooks to turn irony back against itself, drilling past its layers of sophistication and reclaiming the simple appeal that the song hangs from. The attitude of “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me” is at the heart of Trump’s appeal to his supporters.

Sleaford Mods are in a less brash sort of tradition. Williamson puts a great deal of importance on honesty about the place music comes from, and his talent is in his ability to communicate to people without a soapbox or pedestal. The song “Elocution” begins with the sarcastic opening line,

“Hello there, I'm here today to talk about the importance of independent venues. I’m also secretly hoping that by agreeing to talk about the importance of independent venues, I will then be in a position to move away from playing independent venues.”

You can read this as a criticism of Idles and other middle class rockers, but it’s perhaps just as much as a reflection of his anxieties about himself as he grows more successful, as his band gets invited to play larger venues, as he moves his family out from the neighbourhoods that he became famous writing about and into the suburbs. The line’s sarcasm aside, Sleaford Mods are strong supporters of independent venues, which have been hit badly by the pandemic, and in December 2020 contributed a song to a compilation album in support of the Independent Venue Week campaign.

Idles have also been vocal supporters of independent venues, and the 2021 music video for their song “Carcinogenic” was made to support local venues in their hometown of Bristol. The band and their PR machine certainly make a big show out of their cause, but how many venues in Bristol are complaining?

In a way, Idles vocalist Joe Talbot is just staking out his own sort of authenticity in a different territory from Williamson, many of his lyrics and pronouncements coming in the sort of confessional, slightly defensive voice usually encountered on the unsteady ground of social media, but grounded in a sort of positive-minded self-expression — he may not have an “authentic” backstory, but he’s true to himself. On “The Lover” from Idles 2020 album “Ultra Mono”, he addresses his critics in just this voice:

“You say you don't like my clichés / Our sloganeering and our catchphrase / I say, ‘love is like a freeway’ and / ‘Fuck you, I'm a lover’"

Part of the problem may also be that traditional divisions between working- and middle-class have been complicated by changes in society. Idles may not be working class themselves, but the angry yet celebratory voice of their music chimes with the growing class of university-educated, socially-conscious young people trapped in unsteady employment. Despite their struggles and increasingly dim futures, these new members of the recently emerged precariat have been derided as privileged students by a political and media establishment that prefers to see authenticity in twee, nostalgic 1950s fantasies of rural and working class life. They’re tired of being told that (for example) the countryside is more real than their world, when images of rural patriotism come straight off biscuit tins — tired of having their idealism sneered at and derided. To many people, Idles vocalist Joe Talbot cuts through these facile notions of “the real England” and offers a voice that acknowledges their frustration and anger.

“If you’re angry about inequality, you have to preach equality as an alternative rather than go, ‘Fuck you, you’re wrong,’” said Talbot in response to Williamson’s criticisms. “The fact that we’re still talking about the same stuff punks were dealing with in the 1970s means that ‘Fuck you’ thing didn’t work.”

There’s an attitude of “I’m tired of it, and my anger is justified!” that might sound similar to that of the Trump supporters. We should be wary of taking the comparison too far — similarly angry activisms, one fighting for a less cruel society and one storming the Senate in support of a white supremacist, are not the same thing — but there’s something similar in the dynamics. They’re both machines powered by anger (who was it that said “anger is an energy”?), both born from feelings of powerlessness, and also on some level driven from a personal desire for validation — to feel heard. They give people direction in a world that feels like it’s becoming impossibly complicated, but they also divide them into a multitude of voices, all trying to shout out their claims loudest.

Idles seem aware of the divisiveness of much political debate and rhetoric, but their calls for unity (on their own side at least) constantly rub up against Talbot’s essentially individualistic need to speak his own truth. In the song “Grounds”, he accuses his critics of being unconstructive:

“There’s nothing brave and nothing useful / You scrawling your aggro shit on the walls of the cubicle / Saying my race and class ain’t suitable / So I raise my pink fist and say black is beautiful”

To Talbot, he doesn’t want to be held back from making a contribution to issues he cares about simply because of his race and class. To others, though, Talbot’s annoyance at being told what it’s appropriate for him to say or otherwise may seem like a reflection of the core problem: that as a white, middle class man, he feels he has an intrinsic right to take command of any issue he chooses, on anyone’s territory, as well as the right to whatever career benefits that might accrue to him as a result.

When you look at disputes like this from a wide view, they’re obviously not that important — Jason Williamson is probably right when he says that “music can’t solve political problems”, and by extension of that, the political disagreements between musicians themselves are of little consequence. However, if the role of politics in music really comes down to how artists connect to their audiences, this is something both Sleaford Mods and Idles are doing very effectively to slightly different (but also to a large degree overlapping) crowds — one interweaving politics with caustic, surreal and often self-mocking observations of daily life, the other a celebratory insistence on itself and its beliefs that burns through all demands for restraint.

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

COLUMNS

- Columns

♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く - Columns

3月のジャズ- Jazz in March 2024 - Columns

ジョンへの追悼から自らの出発へと連なる、1971年アリス・コルトレーンの奇跡のライヴ- Alice Coltrane - Columns

♯4:いまになって『情報の歴史21』を読みながら - Columns

攻めの姿勢を見せるスクエアプッシャー- ──4年ぶりの新作『Dostrotime』を聴いて - Columns

2月のジャズ- Jazz in February 2024 - Columns

♯3:ピッチフォーク買収騒ぎについて - Columns

早世のピアニスト、オースティン・ペラルタ生前最後のアルバムが蘇る- ──ここから〈ブレインフィーダー〉のジャズ路線ははじまった - Columns

♯2:誰がために音楽は鳴る - Columns

『男が男を解放するために』刊行記念対談 - Columns

1月のジャズ- Jazz in January 2024 - 音楽学のホットな異論

第2回目:テイラー・スウィフト考 - ――自分の頭で考えることをうながす優しいリマインダー - Columns

♯1:レイヴ・カルチャーの思い出 - Columns

12月のジャズ- Jazz in December 2023 - Columns

11月のジャズ- Jazz in November 2023 - 音楽学のホットな異論

第1回目:#Metoo以後のUSポップ・ミュージック - Columns

10月のジャズ- Jazz in October 2023 - Columns

ゲーム音楽研究の第一人者が語る〈Warp〉とワンオートリックス・ポイント・ネヴァー - Columns

〈AMBIENT KYOTO 2023〉現地レポート - Columns

ワンオートリックス・ポイント・ネヴァー・ディスクガイド- Oneohtrix Point Never disc guide

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE