MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

Home > Interviews > interview with Jim O’Rourke - "I don’t make music ‘cause I enjoy it"

interview with Jim O’Rourke

"I don’t make music ‘cause I enjoy it"

──an interview with Jim O'Rourke

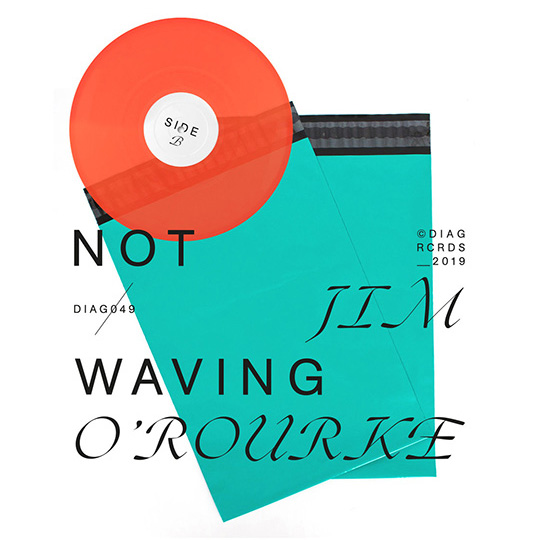

Jim O'Rourke sleep like it’s winter NEWHERE MUSIC |

Writing about a musician like Jim O’Rourke is always a challenge. His work is rarely what it seems to be on the surface, its mechanisms carefully concealed so that how it works on you as a listener is the result of an almost invisible creative process. A huge amount of complexity and musical intelligence underscores music that feels completely natural and even obvious, as if it’s always existed. If his creative approach includes a strong element of academic discipline, his finished music nonetheless has a lot of heart.

On O’Rourke’s previous relatively high-profile release, his unexpected 2015 return to something like rock songwriting with Simple Songs, instantly familiar-sounding rock hooks would merge imperceptably into completely unexpected musical territory without you ever noticing how you’d travelled. His latest album, Sleep Like It’s Winter, released from the new, ambient-focused NEWHERE label, sees him in a radically a different sonic landscape again, with an icy, uneasy, breathtakingly beautiful 45-minute instrumental track.

Between Simple Songs and Sleep Like It’s Winter lie twenty-two separate releases in O’Rourke’s Steamroom series, which he puts out at a rate of about one every couple of months from his Bandcamp page. While some of these releases are old tracks deemed worthy of exhuming from his archives, this rapid flow of releases may also include something for those of us hoping to find clues as to his working. Certainly some of the Steamroom releases that most immediately preceded Sleep Like It’s Winter share similarities.

None of them are quite as richly layered and textured though, and while ambient music is almost by definition music that defies analysis, working primarily on the fringes of consciousness, Sleep Like It’s Winter at the same time feels like a very conscious album, full of ideas and revealing something new on every listen.

I mean, most people would say Eno. Actually it would go back to Michael Nyman’s book Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. It’s a great, important book that I read when I was in high school.

I:

I always find it a bit difficult to talk about music that often gets described as ambient or drone…

J:

Right, well, the fact that they even asked me to make an ambient record for them, that’s why I decided to take the challenge. I didn’t set out to make an ambient record but it’s sort of about making an ambient record more than it’s an ambient record (laughing) you know? Pretty much everything I do is about what it is as opposed to being it.

I:

You’ve said before something along the lines of that you approach making music in a way kind of like a critic.

J:

Yeah, I don’t make music ‘cause I enjoy it. (Laughs) Yeah, I have said something like that. I’m not comparing myself to him but when I was young I read this quote from Godard where he said, “The best way to critique a film is to make another film,” and that stuck with me since I luckily read that as a young boy. That’s fundamental to how I work.

I:

How long did this new album take?

J:

That took about two years.

I:

Were you still living in Tokyo when you started work on it?

J:

I was still in Tokyo, yes, when they first asked me. But there was also a lot of extraneous work around that time also because I was moving. So the first six months of working on it was probably more thinking than actually putting anything down. Just thinking about what the hell that term “ambient” meant, and it means different things to different generations. At the beginning, when they asked me, it was like “We’re starting an ambient label,” and I was like, “Okay…” (laughs) Just making any record in terms of “make a record in this genre” is anathema to me, but I decided to do it because it was such a revolting idea! (Laughs) Not that I dislike ambient music – I don’t mean that. That’s just not the way I think when I make things, so it was such a bizarre proposal that I decided to do it.

I:

For ambient music what is your first natural frame of reference?

J:

I mean, most people would say Eno. Actually it would go back to Michael Nyman’s book Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. It’s a great, important book that I read when I was in high school. There’s a bit about Eno in there talking about, and (Eno) didn’t use the word “ambient” yet, he refers (Erik) Satie’s idea of “furniture music”. And it might be on the back of his Discreet Music record, which was a big deal for me when I was a kid, because on the back of the record it’s all just him talking about these ideas and there’s also diagrams of technically how he made the music. When I think of ambient music I don’t necessarily think of Eno because Eno’s actual ambient music, when he moved on, you know those “Ambient” records, I actually don’t like those very much – no disrespect to him, but it’s just not my cup of tea. In a way I like Satie’s definition of it more: that it’s “furniture music”, that it’s like BGM: it’s not something that’s meant to be listened to with the active mind, which implies that you’re not following the formal structure of what’s going on. So it’s a sort of shift of standpoint that means “ambient” to me. For me, in making this record, the most important thing was, “Where is a line where you decide to give up on formal structures completely?” and, “Where is a line where formal structures can still be perceived but they’re not being shouted at you?”

I:

Speaking of formal structures, going back to Eno, he often seems interested in the idea of taking the musician completely out of the music

J:

For me, in that way of thinking of music, which I’ve been moving towards my entire life slowly but surely (laughs), Roland Kayn was the biggest guy for me. Someone could call his music ambient but it’s way too aggressive for that. The idea of his music is you create the system and then you just let it go. The challenge is how can you create a system that still represents the ideas even though you’ve let it go. If you look at some of the last decade or so of Cage’s scores, like the number pieces, they create these systems. These later Number Pieces of his are really interesting because, if you do them correctly, they’re really constraining even though they don’t seem to be. Whereas someone like Kayn and what Brian Eno were doing, especially in the 70’s, they still want a result but they want to be hands off about it.

I:

For those of us listening to you, it’s almost like we get to hear you, well not in real time but now it almost feels like every couple of months there’s a new thing on Bandcamp

J:

Yeah, Bandcamp is one of the few things the internet has created that I really like. I do like that it’s just there for the fifty people who want it and nothing else gets attached to it. Everything that comes with releasing records, if I have nothing to do with it that’s the happiest I could possibly be. For me, you’ve got to understand, once it’s done it’s done: I’m already gone.

I:

Did your work on those releases inform your work on this new album?

J:

I think one or two might have been failed versions. (Laughs) I mean the Bandcamp stuff, honestly it’s for the 50 or 80 people out there who want to hear that stuff. It’s just being able to be, “Here, you guys want this: go ahead.” Not that I don’t put as much work into those things. For every Bandcamp work I put up, there’s like 80 failed Bandcamp things.

I:

In Sleep Like it’s Winter, there are a lot of sounds that are happening just on the edge of hearing, where it drops to near silence for a while before the sounds build back up again.

J:

Yeah, that’s true. A lot of my really early stuff in the late ’80’s, early ’90’s was a lot of that but I think, because I was young, I was still in the mode of imitating people. I was imitating silence (laughs) because there’s a lot of that, especially in (Giaconto) Scelsi’s music, which I was really really into when I was in college. And I really appreciated the amount of silence in a lot of Luc Ferrari’s work, which I was also really really into.

Also, at that time, things like the Hafler Trio, P-16 D4a, blah blah blah, but I don’t think I really understood how to use that until later in life. Because silence is just as much a part of the dynamic as something loud. In the act of actually listening to something, time means a lot and silence is also time because you perceive time differently in silence than time with sound. Hopefully, the use of silence stretches your perception of time – it’s the same thing as having a good drum fill or something.

by Ian F. Martin(2018年6月25日)

| 12 |

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

INTERVIEWS

- interview with xiexie - オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- interview with salute - ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる ──サルート、インタヴュー

- interview with bar italia - 謎めいたインディ・バンド、ついにヴェールを脱ぐ ──バー・イタリア、来日特別インタヴュー

- interview with Hiatus Kaiyote (Simon Marvin & Perrin Moss) - ネオ・ソウル・バンド、ハイエイタス・カイヨーテの新たな一面

- interview with John Cale - 新作、図書館、ヴェルヴェッツ、そしてポップとアヴァンギャルドの現在 ──ジョン・ケイル、インタヴュー

- interview with Tourist (William Phillips) - 音楽はぼくにとって現実逃避の手段 ──ツーリストが奏でる夢のようなポップ・エレクトロニカ

- interview with tofubeats - 自分のことはハウスDJだと思っている ──トーフビーツ、インタヴュー

- interview with I.JORDAN - ポスト・パンデミック時代の恍惚 ──7歳でトランスを聴いていたアイ・ジョーダンが完成させたファースト・アルバム

- interview with Anatole Muster - アコーディオンが切り拓くフュージョンの未来 ──アナトール・マスターがルイス・コールも参加したデビュー作について語る

- interview with Yui Togashi (downt) - 心地よい孤独感に満ちたdowntのオルタナティヴ・ロック・サウンド ──ギター/ヴォーカルの富樫ユイを突き動かすものとは

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第3回 『天乃川』とエレクトロニク・ミュージック

- interview with Sofia Kourtesis - ボノボが贈る、濃厚なるエレクトロニック・ダンスの一夜〈Outlier〉 ──目玉のひとりのハウス・プロデューサー、ソフィア・コルテシス来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Lias Saoudi(Fat White Family) - ロックンロールにもはや文化的な生命力はない。中流階級のガキが繰り広げる仮装大会だ。 ——リアス・サウディ(ファット・ホワイト・ファミリー)、インタヴュー

- interview with Shabaka - シャバカ・ハッチングス、フルートと尺八に活路を開く

- interview with Larry Heard - 社会にはつねに問題がある、だから私は音楽に美を吹き込む ——ラリー・ハード、来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回 「ロリー・ギャラガーとレッド・ツェッペリン」そして「錦糸町の実況録音」について

- interview with Mount Kimbie - ロック・バンドになったマウント・キンビーが踏み出す新たな一歩

- interview with Chip Wickham - いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 ──サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with Yo Irie - シンガーソングライター入江陽がいま「恋愛」に注目する理由

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第1回 「エレクトリック・ピュア・ランドと水谷孝」そして「ダムハウス」について

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE