MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

Home > Interviews > interview with Michael Gira(Swans) - 音響の大伽藍、その最新型

interview with Michael Gira(Swans)

音響の大伽藍、その最新型

──マイケル・ジラ、インタヴュー

ニューヨークのノー・ウェイヴ勢がその崩壊型のアート虐殺行為を終えつつあったシーン末期、1982年にスワンズは出現した。1983年のデビュー作『Filth』のインダストリアルなリズムと非情に切りつけるギターから2016年の『The Glowing Man』でのすべてを超越する音響の大伽藍まで、彼らは進化を重ね、長きにわたるキャリアを切り開いてきたが、次々に変化するバンド・メンバーやコラボレーターたちの顔ぶれの中心に据わり、スワンズの発展段階のひとつひとつを組織してきたのがフロントマンのマイケル・ジラだ。

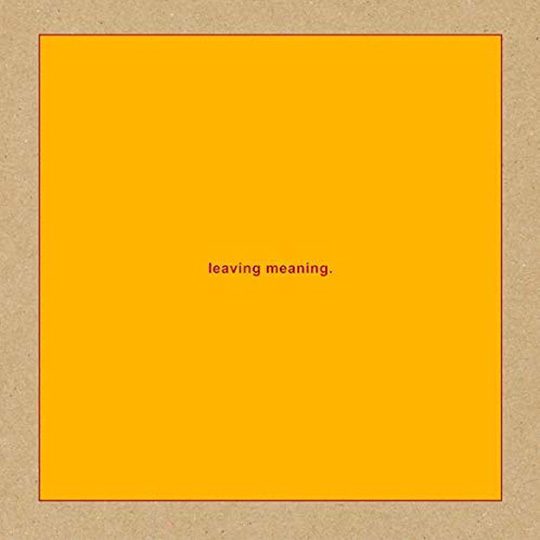

実験的な作品『Soundtracks for the Blind』に続き、スワンズは1997年にいったん解散している。そこからジラはエンジェルズ・オブ・ライトでサイケデリックなフォーク調の音楽性を追求した後、新たなラインナップでスワンズを再編成しこの顔ぶれで2010年から2016年にかけて4作のアルバムを発表。じょじょに変化を続けるジラのサイケデリックからの影響を残しつつ、それらを音の極点のフレッシュな探求に融合させた作品群だった。このラインナップは2017年に解消されたものの、それはバンドそのものの終結、というか長期の活動休止を意味するものですらなかった。そうではなく、ジラは自らのアイディアの再配置を図るべく短い休みをとった上で、『Leaving Meaning』に取り組み始めた。クリス・エイブラムス、トニー・バック、ロイド・スワントンから成るオーストラリアの実験トリオ:ザ・ネックスから作曲家ベン・フロスト、トランスジェンダーの前衛的なキャバレー・パフォーマー:ベイビー・ディーに至る、幅広い音楽性を誇るコラボレーターたちが世界各国から結集した作品だ。

マントラ調になることも多い執拗なリズムとグルーヴ、トーン群とサウンドスケープの豊かな重なり、ゴスペル的な合唱によるクレッシェンドとが、今にも崩れそうなメロディの感覚で強調された、霊的な音の交感の数々へと統合されている。このアルバムおよびその創作過程の理解をもう少し深めるべく、筆者はアメリカにいるジラとの電話取材をおこなった。取材時の彼はこれまでも何度かコラボレートしてきたノーマン・ウェストバーグを帯同しての短期ソロ・ツアーに乗り出す準備を進めているところだったが、それに続いて彼は2020年から始まる『Leaving Meaning』ツアー向けの新たなスワンズのライヴ・ショウ作りに着手するそうだ。(坂本麻里子訳)

わたしはドアーズを聴いて育ったんだ。大げさな音楽だったかもしれないけど、その当時はすごくいいと思ってた。いまでもその頃聴いてたレコードのことを思い出すよ。

■アルバムを聴いたのですが、かなり手の込んだプロセスだったのではないでしょうか。参加したアーティストも30人以上います。

ジラ:6ヶ月やそこらかかったんじゃないかな、いや、8ヶ月だったかも。ようやく作り終えたのがたしか3ヶ月前。かなりの作業だった。

■大部分をドイツで録られましたね。なぜドイツだったのでしょう?

ジラ:メインで参加してくれてるアーティストがベルリン在住だった。ラリー・ミュリンズ、クリストフ・ハン、ヨーヨー・ロームとまず元になるトラックを録って、その後サポート(と言えども、重要な役割の)ミュージシャンを呼んだわけだけど、彼らもベルリン在住だったからね。ベルリンには他にも何人か呼び寄せて、素晴らしきベン・フロストと作業するためにアイスランドに飛んだよ。ニューメキシコ州のアルバカーキにも行って、A Hawk and a Hacksawのヘザーとジェレミー、昔からの友人のソー・ハリスとも作業した。で、ブルックリンでダナ・シェクター、ノーマン・ウェストバーグ、クリス・プラフディカのパートを録って、またベルリンに戻ってオーヴァーダブとミックス作業をしたんだ。

■以前とはかなり異なるプロセスだったのですか?

ジラ:うーん、2010年から2017年、18年くらいまでは固定のバンド・メンバーがいた、メンバー間の仲も良かったし、みんないいミュージシャンだった。スタジオに入って、ライヴ演奏してきたものや、わたしがアコースティック・ギターで書いた曲に肉付けしたものを録ったりした。いつも一緒にやっている人は決まっていて、外部から人を連れてきたりもしたけど、ベースになる部分はずっと同じだった。スタジオに入って、全てをレコーディングしたりもした。わたしが不在のこともよくあったけど、いまみたいに大世帯ではなかったんだ。その当時のバンドを解散してからは、曲に見合って、作り上げてくれる仲間を選ぶようにした。

■アルバム、『My Father Will Guide Me up a Rope to the Sky』(2010)から『The Glowing Man』の流れでいくと、先に広がりを持つ曲作りをされたということでしょうか?

ジラ:まずわたしがアコースティック・ギターのみで録って、そのあとみんなでスタジオで作りこんでいった曲もあるよ。他の曲はライヴでやったものを使ったりもした。アコースティック・ギターから生まれたグルーヴをスタジオでみんなとプレイして、エレクトリック・ギターを乗せて、バンドとして曲を作りこんでいく感じ。そこから、ライヴ演奏して、わたしひとりじゃなくて、曲が展開するに従って、バンドとしてインプロしていく。こういった断片的なものを生でプレイして、積み重なって、どんどん構築される──30分の曲もあれば、50分の曲もある。ある曲を演奏しているうちに、新たな流れができて何かが生まれて、元にあった部分を切り捨てたりとかね。わたしたちの曲は常に進化系だから、その先の流れも見えてくる。なかなか面白いやり方だったと思う。

■かなり前に作られた曲の断片を再度使い、新しいものに生まれ変わらせる、といったプロセスなようにも取れますね。例えば、『The Glowing Man』内の“The World Looks Red/The World Looks Black”は80年代にサーストン・ムーアのために書かれた歌詞が引用されています。

ジラ:音楽が完成することは決してないと思っている。今回のアルバムの曲にしても、新しいバンドと演奏すれば、また新たに進化していくものだろうし。むしろそうであってほしい。アルバムと全く同じように聴こえるのではつまらない、新しいかたちでで演奏できる術を見出したい。常に崖っぷちにぶら下がってる感覚が大切なんだ。まがりないものを作り出すにはいい刺激なんじゃないか。

■そういった意味では、今回のアルバムを作る過程は以前とは逆のやり方だった、と?

ジラ:そうかもしれない。ただ、今回のアルバムの構成・作曲に関していうと、作りはじめはむき出しの状態。いままでに演奏したことがあるものじゃないから、構成、作曲、ミックス、プロダクションという流れだった。以前に存在していたものではなかったから、だから自分のよく知るやり方でベストなアルバムを作ったのみ。で、想像つくと思うけど、このでき上がったものを思い切りぶち壊すのが次のステップ(笑)。

■ご自身のアコースティックのデモを事前にリリースし、今回のアルバム制作資金を調達しました。以前にもこのやり方をされたことがありますね。

ジラ:何度もね。曲が反復する部分があるんだけど、そこからその曲のごく初期のヴァージョンや、アウトラインが見えてくると思う。ただ、こういう曲をアルバムと比べると、相当変化を遂げている。あるものが常に進化段階だという事実は重要だ。

■レコーティングされたものとライヴ音楽の関係性について。ライヴ体験は独特の身体的若しくは直感的な何かがあるように思えます。

ジラ:そうだね、特に前作から感じ取れたと思うけど(笑)。音量重視だったからね。それには訳があって、ただ単に音量をあげたかったのではなくて、そこまでの音量にしないとしっくりこなかったっていうのがあった。これからのライヴではもうそのやり方はしないけど。それなりの音量にはなるが、以前のように音量に圧倒される体験ではなくなるね。

■それを聞いて、以前ブライアン・イーノが言ったことを思い出しました。何かが限界ギリギリになったときにこそ、クリエイティヴィティが生まれる、と。例えば、スピーカーを最大音量まであげたときに、ディストーションという新しい音の形が生まれるように。

ジラ:ああ、想定外のものが生まれるのをみるのは楽しい。わたしも最初に作ったものを捨てて、予想外の産物を使うことがよくある。そっちの方が熱がこもってる気がするから。

■かなり冒険的なアプローチですよね。それはご自身が元々ミュージシャンとしての訓練を受けていないことに起因していると思いますか?

ジラ:そうだな、わたしがギター・プレイヤーと曲作りをしているとする。わたしが自分のギターでコードを弾いて、「もうちょっとオープンコードっぽく弾いてみて」と頼んで、弾いてもらう。で、「あー、ちょっと違うな。もっと高いコードでやってみようか。それかハモってみるか」って具合に。その曲にしっくりくるものを探すのみ。だいたいわたしが曲を書くときはアコースティック・ギターを使うんだけど、ギターに腹が触れてるもんだから腹で音を感じるんだよ。わたしが弾くコードにはオーヴァートーンや共鳴があって、曲を組み立てていく段階になると、むしろコード主体というよりもコードを取り囲むサウンドがメインになること多い。そうすると、「そうか、そこに女性ヴォーカルかホーンを入れたらこの共鳴部分を引き出すことができるのかもしれない」ってなるから、そうやって曲が作り上げられていく。

だから自分のよく知るやり方でベストなアルバムを作ったのみ。で、想像つくと思うけど、このでき上がったものを思い切りぶち壊すのが次のステップ(笑)。

■ギターの共鳴を身体で感じるとおっしゃっていましたが、音楽の身体性について思い出しました。

ジラ:ああ、まあ、わたしはある意味、サウンドにのめり込んで消えてしまいたいっていう、こう、青臭い衝動に駆られるから、スケールはでかければでかいほどいいんだけど。ただ当然、長いこと生きていれば、でかいサウンドにしたいんだったらそれなりにサイズ感を合わせていかなきゃいけないことを学ぶわけで。青臭いっていったのは、若かりし頃に音楽に没頭して、そのなかに埋もれるとどこか新しい場所に辿り着けたことを思い出したから。だから、ステレオの音量をグッと上げるんだよ、しばしのあいだこの世から消えてしまいたいと思うから(笑)。

■わたしの青春時代はいつもシューゲイザー・ミュージックでしたね。音の渦に飲み込まれますから、音楽的にはひどいものだったかもしれませんけど。

ジラ:申し訳ないけど、中身のない音楽だな(笑)!

■その当時は自分自身の中身も空っぽだったんだと思います!

ジラ:わたしはドアーズを聴いて育ったんだ。大げさな音楽だったかもしれないけど、その当時はすごくいいと思ってた。いまでもその頃聴いてたレコードのことを思い出すよ。

■そう考えると、最近のスワンズのサウンドはドアーズ特有のエコーを彷彿させるものがありますね。サウンドそのものというよりも、雰囲気ですけど。

ジラ:まあそうだな、ドアーズはわたしの一部になってるから。ジム・モリソンみたいに歌えたら、もう死んでもいいや、だってそれ以上の幸せなんてないだろ(笑)。

■ノイズやノイズ・ロックのような音楽の極限を追求する音楽は多々ありますが、80年代、90年代のアーティストがもともとこの音楽的な限界を作り始めたように思います。どのようにしてご自分の限界に挑み続けられているのでしょうか。

ジラ:その当時、スワンズは“ノイズ”音楽だと言われてたみたいだが、そう思ったことは一度もない。“サウンド”──純粋なサウンド、と捉える方が個人的にはしっくりきた。“ノイズ”と言われてたことを気にすることもなかったが、常に自分のやり方で、自分にとって唯一無二の、本物の音を追求してきたつもりだ。

■そういった意味でこのように音楽に限界を設けるのは、音楽的な違反を犯すということなのかもしれません。

ジラ:他人が何をしようと関係ないさ。ルールを破りたいのあれば、どうぞご勝手に(笑)! そうしたところで、結局またそのルールとやらに縛られることになるんじゃないかと思うけど。やりたいことは自ら見つけるべきだし、それが人を不快にさせるなら仕方ないこと。ただそうと決めても、またその事実に結局は囚われることになる。誰かが決めたルールのなかで音楽は作りたくはない。

■今回のアルバムに話を戻します。『The Glowing Man』に比べると、歌詞重視なように思えます。

ジラ:かなり意図したものだ。特に過去の『The Seer』、『To Be Kind』、『The Glowing Man』の3作に関しても歌詞はそれなりに重要だったんだけど、若干陰に隠れていたのかもしれない。歌詞がゴテゴテしすぎたり、奇抜すぎたりすると、サウンド体験の妨げになりうると思ったから。今回はこのサウンドに見合うものを生み出すことに挑戦した。ある意味、ゴスペルみたいな感じだよね。何度も繰り返されるフレーズがあって、それが昂揚していくような。だから、物語調のものより、サウンドに意味をもたせてくれるようなアンセムとかスローガンみたいなフレーズを見つけようと思ったんだ。今回の新しいプロジェクトでは、もっと歌詞を書くと決めて、アコースティック・ギターを持って自分をなかば強制的に歌詞に集中させるところからはじまった。湧き出てくる言葉もあれば、どうしてもうまい具合に出てこないこともあったけど。

■インプロを多用し、生で演奏し作り上げていくというスタイルから、より構造的なものにしていこうというプロセスの変化の一端だということですか?

ジラ:ああ、そうだね。歌詞は明らかに完成してるけど、そこからまた曲が進化していくっていうときもあったね。歌詞ができていないときでも、イメージしているものがあがってくるまで、適当なフレーズで歌ってたときもあった。で、そのイメージと他のイメージの相乗効果で曲ができたり。その場合、全ての曲はすでに完成していて、あとはその曲を演奏してる人たちと詰めていくだけだった。

■このアルバムの制作過程で歌詞から何かテーマが生まれてきましたか?

ジラ:どうだろう。いつも自分自身の存在に惑わされ、驚かされてるからさ。自分の精神、一般的にいう精神というものがどういうものなのか、意識とはどういう仕組みなのか理解しようとしているんだけど、もしテーマがあるとしたらそれかな。君が若い頃にこういう経験があったかどうかわからないけど、わたしには間違いなくあった、とくにLSDをやったときにね。鏡のなかの自分の姿をある一定の時間眺めていると、自分が肉体から離れていくのが見えて、鏡のなかの人物は自己というものを失う、この現象。こういった心理状態は興味深いものだ。

■歌詞やサウンドについて。“Amnesia”を例にとります、もしかしたらわたし自身の不安を投影しているだけかもしれませんが、世のなかが制御不能に陥っていくような印象を受けました。

ジラ:さあ、いまの世のなかについてどうこう言えるほどの立場にないからなんとも言えないけど、自分の頭のなかがどうなってるかはよくわかってるつもりだ(笑)。

まあ、わたしはある意味、サウンドにのめり込んで消えてしまいたいっていう、こう、青臭い衝動に駆られるから、スケールはでかければでかいほどいいんだけど。

■先ほど、ゴスペル音楽についてお話されていましたが、今回のアルバムにもその要素が入っているように思えました。このような音楽は、宗教的な救済を彷彿させるのではないでしょうか。

ジラ:うーん、救済、ではないかな。救済っていうんだったら、まずは呪われていることが前提じゃないか。恍惚的な何かに解けこんでいくっていう考え方は、もちろん音楽の本質だけどね。それは常に追い求めている。曲ってシンプルなものだったり、短編的なものだったりするんだけど、サウンドのなかで我を見いだしたり、見失ったりってことを同時にやっているってことでもあるんじゃないか。

■“Leaving Meaning”では最近話題のドイツの「Dark」というテレビ・ドラマのサントラを担当してるベン・フロストが参加していますね。映画ファンなんですか?

ジラ:映画オタクってわけでもないし、すごく詳しいわけじゃないけど、映画はよく観るよ。近代では一番わかりやすい芸術の形なんじゃないか。個々の持つ力をうまく引き出して、自分のヴィジョンを維持しつつ、そこから芸術作品を作り出すって、とてつもないことだと思うんだ。まとめていかなきゃいけない人たちからあれこれ言われたり、経済的な困難だとか、それを全て乗り越え、ものすごく手の込んだ何かを生み出すのはとてつもない労力だ。

■いまお話にあった、手が込んで、包括的な芸術作品である映画のように、あなたが音楽的に成し遂げたいなにかはありますか? アルバムを聴いていると、単に個々の曲を寄せ集めただけではないような気がします。

ジラ:80年代後半か、もしかしたら80年代なかばくらいから、アルバムをサウンドトラックとしてとらえるようになった──エナジー、わたしたち独自のサウンドそして昂揚感が詰まったものとして。音を通じて、完全なる体験を作り出したかったんだ。自分が映画を撮ったり、脚本を書いたりなんて腕は全くないが、こういった体験に音を落とし込んでいくことだけはできる。

■それは曲や音楽の欠片が他のものに移り変わっていく過程なのではないかとわたしも思います。

ジラ:以前のアルバムだと、音の継続性や遷移性は少し掘り下げてみるだけだったこともあったが、『Soundtracks for the Blind』(1996)あたりから、それを実際に採用してみたら面白いんじゃないかと思うようになった。だからその流れに乗って、曲を作ってみようってなったんだ。「お、面白いやり方が見つかった、遷移的で形のない瞬間を紡いでいこう」って思ったのを覚えてる。

■最後になりますが、次のステップとして今回のアルバムをライヴで実現したいとおっしゃっていましたね。どのようにして実現されるか、若しくはどのようなセットアップにされるか決めているのですか?

ジラ:まだあまり公にするつもりはないんだけど、6人編成で、座っての演奏になる予定。延々と伸びた音の洪水がポイントになって、そこから曲が展開していくっていう変わった編成の予定だけど、どうなるかね! リハの期間は3週間あるから、なかなか面白いことになりそうだ。このツアーで新しいバンドと一緒に作り込もうと思っている曲はあるんだ。これからはじまるソロ・ツアーが終わったら、彼らとのツアーだけでプレイ予定の新曲が完成しているはず。いいサウンド体験にできればいいんだけど。

■現在のセットアップにインプロを取り入れる予定は?

ジラ:ああ、そうだね、それもいいなとよく思ってる。それにはまずコード構成をちゃんとおさえて、それからどうやってそれをぶち壊すかを考えないとだな(笑)!

Emerging in 1982 into the disintegrating art-carnage of the New York no wave scene’s dying days, Swans have carved out an enduring career that has evolved from the industrial rhythms and harsh guitar slashes of their 1983 debut Filth through to the transcendent sonic cathedrals of 2016’s The Glowing Man, with frontman Michael Gira orchestrating each evolutionary step from the centre of an ever-shifting lineup of bandmates and collaborators.

Swans disbanded in 1997, following the experimental Soundtracks for the Blind, with Gira pursuing a psychedelic folk-tinged direction with Angels of Light before reforming Swans under a new lineup for a run of four albums between 2010 and 2016 that retained Gira’s evolving psychedelic influences and fused them to fresh explorations of sonic extremes. The dissolution of that lineup in 2017 didn’t herald the end of the band though, or even an extended hiatus. Instead, Gira took a short break to reconfigure his ideas and began work on Leaving Meaning, bringing together a worldwide cast of musically divcerse collaborators ranging from Chris, Tony Buck and Lloyd Swanton of Australian experimental trio The Necks through composer Ben Frost to transgender avant-cabaret performer Baby Dee.

The album synthesises insistent, often mantric rhythms and grooves, richly layered tones and soundscapes, and gospel-like choral crescendos into moments ecstatic sonic communion underscored with a frequently fragile melodic sensibility. To try to understand a bit more about the album and the process behind it, I spoke with Gira by phone from the United States, where he was preparing to embark on a short solo tour with occasional collaborator Norman Westberg before working on creating a new live Swans show to tour Leaving Meaning in 2020.

IM:

Listening to this album, it feels like it was quite an involved process, and looking at all the people you collaborated with, there’s more than thirty people on the album.

MG:

It took six months or something – maybe eight months – and I finished three months ago, maybe. It was quite involved.

IM:

You recorded a lot of it in Germany. Why did you take that decision?

MG:

Some of the main players lived in Berlin. Larry Mullins, Kristof Hahn and Yoyo Röhm were the people with whom I first recorded the basic tracks, and then other ancillary musicians, although ultimately of equal importance, also lived in Berlin. I flew some people into the studio in Berlin as well, and then I travelled to Iceland as well, to work with the wonderful Ben Frost. I also travelled to Alberqurque, New Mexico, and worked with Heather and Jeremy from A Hawk and a Hacksaw and my old friend Thor (Harris). And then I travelled to Brooklyn and recorded Dana Schechter, Norman Westberg and Chris Pravdica and a few other things, and then I went back to Berlin and did some more overdubs and mixed.

IM:

Is that a very different process from the way you’ve worked previously?

MG:

Well, from 2010 to 2017-18 I had a fixed band for a while – great friends, great musicians – and we had a thing, so we’d go into the studio and record the material we had worked on live perhaps, or things that I had written on acoustic guitar we fleshed out. I had a set group of people with whom I worked, and then I would bring in other people to add orchestrations, but I had a basic group. We would go into the studio and record everything – I’d travel around a bit, but there weren’t as many people involved. Since I decided to disband that group, I just chose the people, whomever they might be, that served the song and helped orchestrate the song.

IM:

So on that run of albums from My Father Will Guide Me up a Rope to the Sky through The Glowing Man, the songs were built up live to a greater extent?

MG:

There are songs on there that I wrote exclusively on acoustic guitar and then we orchestrated them in the studio. Other ones came through playing live. I would have maybe a groove on the acoustic guitar and then I would go and rehearse with those gentlemen and I’d play electric guitar and then as a group we’d build it up and develop the song. And then we’d play it live and we had a tendency to improvise as a group – not solo, but improvise as the music unfolded. These long pieces developed just through performing, some of them thirty minutes long, sometimes fifty minutes long – it would just grow and grow. And sometimes what would happen is we’d have a song we were playing and a new thing would happen, which would become a new song and we’d leave the old bit behind, so it was always evolving and we’d find a new path forward. It was an interesting way to work.

IM:

There also seemed to be this process where fragments of old songs from a long time ago would re-emerge and gain a new lease of life. For example, on The Glowing Man using lyrics you’re written back in the ’80s for Thurston Moore in the song The World Looks Red/The World Looks Black.

MG:

I don’t look at the music as ever being finished. Even the songs from this album, I’m going to perform some of them with a new group and I expect that they’ll change considerably. I want them to – I don’t want them to sound like the record: I want to find a new way to perform them. It’s always important to me to be dangling over the cliff and having failure nipping at your toes. It’s a good impetus to make something authentic happen.

IM:

So in that sense, was the process behind Leaving Meaning almost in some ways the reverse of the ways you’d been working previously?

MG:

Maybe so. However, the way that this was composed and orchestrated was naked at the beginning. There wasn’t a history of playing it, so it was composing, orchestrating, mixing and producing this thing in and of itself. It didn’t have a life previous to that, so I just made the best record I knew how to do. And now, of course, the next thing to do is to fuck things up as much as possible (laughs).

IM:

You helpeed fund this album with a collection of your acoustic demos as well, right? You’ve done similar things in the past too.

MG:

Many times, yes. There’s one iteration of the songs and you can see the skeletal, nascent version of the songs, but as you compare those to the album, they’re obviously transformed quite a bit. Things are always in process, I think that’s important.

IM:

In terms of the relationship between recorded and live music, there’s also something physical or visceral that is unique to the live experience.

MG:

Yeah, particularly with the last version of Swans you felt it (laughs). It was very volume-intensive. And for a reason: it wasn’t just to be loud, it was that it didn’t sound right unless it was loud. But I’m leaving that behind in the next performances. It’ll have some volume, but it won’t be the overwhelming experience that it was in the past.

IM:

That reminds me of something that I think Brian Eno once said, about how creativity often emerges when something is pushing against its limits, for example in the way that volume pushing against the maximum carrying capacity of the speakers creating new sounds in the form of distortion.

MG:

Yeah, I enjoy that. I enjoy when unexpected results occur, and oftentimes I will discard the original thing and go with these unexpected results because they seem to have more fire in them.

IM:

That seems like quite an exploratory approach, and do you think it has something to do with you not being a formally trained musician?

MG:

Well, say I’m working with a guitarist and I’ll have a chord on my guitar and I’ll say, “Why don’t you try this, more of an open chord?” and then they’ll try something and I’ll say, “Ahh, not quite. Maybe move up the neck or let’s do a harmony.” It’s just searching for what works with the song. Usually, if I’m playing a song with an acoustic guitar, which I do when I’m writing, I can feel it in my belly because the guitar’s resting against my belly and there’s these overtones and resonances that are in the chords I play, and often the orchestration is inspired by what I hear around the chord rather than the chord itself. So I might think, “Oh, maybe I can bring out that resonance if I added some horns or some female vocals,” so things start to grow in that way.

IM:

What you said about the resonances of the guitar against your body brings me back to the idea about the physicality of music.

MG:

Yeah, well, I have a kind of adolescent urge to disappear in the sound, so I usually want things bigger and bigger. Of course, I’ve learned over the years you actually have to make things small also in order for something to sound big. I say adolescent because I associate it with my younger days listening to music, and just to disappear in the music and it kind of takes me somewhere. That’s why you turn up your stereo really loud: because you just want to be erased for a while, you know? (Laughs)

IM:

That reminds me of when I was a kid and my teenage crybaby music was always shoegaze. Even when the music was horrible, I could just disappear into the sound.

MG:

Unfortunately, the music had no content! (Laughs)

IM:

Probably back then I had no content myself either!

MG:

I grew up listening to The Doors. Maybe melodrametic, but it was pretty fantastic. I still think about those records sometimes.

IM:

I can definitely feel some echo of The Doors in recent Swans, at least in the feeling if not exactly the sound.

MG:

Yeah, I mean it’s there in me, for sure. If I could sing like Jim Morrison, I’d immediately kill myself because I’d be so happy. (Laughs)

IM:

With a lot of music that explores sonic extremes, like noise or noise-rock, it sometimes feels as if those limits were already charted by artists in the 1980s and ’90s. How do you keep on being able to challeenge yourself?

MG:

Well, I realise the word was bandied about in regards to Swans back in the olden days, but I never agreed with the term “noise” as applied to us. “Sound” – pure sound would have been a better term for me. But I’ve always followed my own path, and what I think sounds real and not redundant or phony is what I pursue.

IM:

In that sense, maybe thinking of sonic limits in these terms is similar to the idea of transgression, which I know is an idea you don’t necessarily agree with.

MG:

Oh, I don’t care what people want to do. If they want to transgress, all power to them! (Laughs) It just seems like that puts you in the position of a captive in a way, nipping at the heels of your master. To me, one should just choose their own destiny and if that bothers people, fine, but if you make that the point, then you’re necessarily beholden to the people that you’re trying to bother.

IM:

To return to Leaving Meaning, it felt like a more lyrically dense album than, say, The Glowing Man.

MG:

That’s very intentional. The thing is, with the last three records in particulat – that would be The Seer, To Be Kind and The Glowing Man, the lyrics were important, but they took kind of a back seat because if the words were too baroque or ornate, it tends to distract from the experience of the sound. So my challenge was to create signifiers that worked with the sound. Sort of like gospel in a way – you know, you’ll have a phrase that keeps repeating and that ties in with the crescendo. So the challenge was to find words that were more like anthems or slogans rather than someone telling a story, and that would just add meaning to the sound. In this new project, I decided I wanted to write more, so I sat down with an acoustic guitar and forced myself to keep working on the words and they develpped. Sometimes the words flowed and others it was just hacking away with an icepick at a mkountain.

IM:

Is that then partly a function of the change in process from building up the songs live with a lot of improvisation to something more compositional?

MG:

Yeah. I mean, there are some instances in that period where I had clearly finished words and then the songs grew from that, but in other things I wouldn’t have words, and even live I’d be singing nonsensical phrases until an image appeared, and then gradually that image would inspire other images and then I’d have a song. But in this instance, the songs were all there, written, and it was a case of finding life in them with the people that interpreted them.

IM:

Did you notice any themes emerge from the lyrics through thr process of writing this record?

MG:

I don’t know. I’m perpetually befuddled, flummoxed and astonished just by the fact of my own existence, you know? Trying to figure out how my mind works or how a mind works, how consciousness works, and if there’s any theme, it’s that. I don’t know if you had this experience when you were young – I certainly did, particularly when I took LSD – but staring at your face in the mirror long enough, you become disembodied and this person in the mirror loses all sense of being you: it’s just this phenomenon. That kind of frame of mind interests me.

IM:

In the lyrics and music of some songs, for example Amnesia, and I may be projecting my nown anxieties here, but I got the impression of a world spiralling out of control.

MG:

I don’t have an authoritative enough perspective enough to make comments about the world in general, but as far as questioning the reality of my own mind, I’m pretty good at that. (Laughs)

IM:

You also brought up gospel music earlier, and that’s also a soun d and feeling that ceme through on this album. That’s a kind of music that traditionally has been concerned with the idea of salvation.

MG:

Well, I don’t know about salvation. Salvation would presuppose that you’re damned to begin with, but the idea of dissolving into something ecstatic of course is inherent in music, so I’m always looking for that. Sometimes the songs are simple and it’s just a little vignette, but sometimes it’s about simultaneously finding and losing yourself in the sound.

IM:

On Leaving Meaning you worked with Ben Frost, whose work on the soundtrack to the German TV drama Dark was very well received recently. Are you a big fan of cinema?

MG:

I’m not a cinephile – I’m not an expert or anything – but I definitely enjoy movies. I think of the last century, it’s the most comprehensive artform. I have tremendous admiration for an auteur director who can harness all these different forces, keep a vision and manage to forge a work of art out of it. You can imagine all the things tugging at you from every direction from all the people you have to pull together, all the financial travails you have to endure, and making this completely immersive out of it I think is just tremendous.

IM:

In creating these immersive, all-encompassing works of art, is there a parallel with what you try to achieve musically? Increasingly your albums seem to be aiming for something more than just a collection of discrete songs.

MG:

Since the late ‘80s or even mid-‘80s I started to look at albums in a way as soundtracks, replete with all the dynamics and signature sounds that might appear, the crescandos, and just trying to create a total experience through sound. I certainly don’t have it in me to direct a film – or write a film, for God’sb sake! – but I can forge sound into these experiences.

IM:

That’s about the way one song or piece of music transitions into another I guess, too.

MG:

There was a period in Swans, on the album Soundtracks for the Blind, where in previous albums I’d been exploring just that – these segues or transitions – and then I decided around Soundtracks for the Blind that the more interesting thing was the segues or transitions, so I sort of followed those to make the music rather than trying to have songs – or too many songs, anyway. So I thought, “Oh, there’s an interesting avenue to pursue: these transitional, amorphous moments.”

IM:

So lastly, as you mentioned, the next stage is to take this album live. Do you have a plan for how you’re going to do that or what sort of setup you’ll employ?

MG:

I guess I’m not supposed to talk about it yet, but it’ll be six people, and we’ll all be sitting down. The instrumentation is kind of odd, and I think the emphasis is going to be on extended waves of sound punctuated by moments where a song arises, so we’ll see what happens! We have three weeks of rehearsals to make a band, so it should be interesting. I have songs that we’ll work on and hopefully after I finish this solo tour I’m about to embark upon, I’m going to have a couple of new songs written just for the tour with these people in mind that will be playing live and hopefully we’ll make a great experience.

IM:

And will you still be trying to incorporate space for improvisation into the setup you’re buiolding?

MG:

Oh, yeah, that always interests me. First people have to learn the chord structires, and then we have to learn how to destroy them! (Laughs)

取材・文:イアン・F・マーティン(2019年10月25日)

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

INTERVIEWS

- interview with xiexie - オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- interview with salute - ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる ──サルート、インタヴュー

- interview with bar italia - 謎めいたインディ・バンド、ついにヴェールを脱ぐ ──バー・イタリア、来日特別インタヴュー

- interview with Hiatus Kaiyote (Simon Marvin & Perrin Moss) - ネオ・ソウル・バンド、ハイエイタス・カイヨーテの新たな一面

- interview with John Cale - 新作、図書館、ヴェルヴェッツ、そしてポップとアヴァンギャルドの現在 ──ジョン・ケイル、インタヴュー

- interview with Tourist (William Phillips) - 音楽はぼくにとって現実逃避の手段 ──ツーリストが奏でる夢のようなポップ・エレクトロニカ

- interview with tofubeats - 自分のことはハウスDJだと思っている ──トーフビーツ、インタヴュー

- interview with I.JORDAN - ポスト・パンデミック時代の恍惚 ──7歳でトランスを聴いていたアイ・ジョーダンが完成させたファースト・アルバム

- interview with Anatole Muster - アコーディオンが切り拓くフュージョンの未来 ──アナトール・マスターがルイス・コールも参加したデビュー作について語る

- interview with Yui Togashi (downt) - 心地よい孤独感に満ちたdowntのオルタナティヴ・ロック・サウンド ──ギター/ヴォーカルの富樫ユイを突き動かすものとは

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第3回 『天乃川』とエレクトロニク・ミュージック

- interview with Sofia Kourtesis - ボノボが贈る、濃厚なるエレクトロニック・ダンスの一夜〈Outlier〉 ──目玉のひとりのハウス・プロデューサー、ソフィア・コルテシス来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Lias Saoudi(Fat White Family) - ロックンロールにもはや文化的な生命力はない。中流階級のガキが繰り広げる仮装大会だ。 ——リアス・サウディ(ファット・ホワイト・ファミリー)、インタヴュー

- interview with Shabaka - シャバカ・ハッチングス、フルートと尺八に活路を開く

- interview with Larry Heard - 社会にはつねに問題がある、だから私は音楽に美を吹き込む ——ラリー・ハード、来日直前インタヴュー

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第2回 「ロリー・ギャラガーとレッド・ツェッペリン」そして「錦糸町の実況録音」について

- interview with Mount Kimbie - ロック・バンドになったマウント・キンビーが踏み出す新たな一歩

- interview with Chip Wickham - いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 ──サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with Yo Irie - シンガーソングライター入江陽がいま「恋愛」に注目する理由

- interview with Keiji Haino - 灰野敬二 インタヴュー抜粋シリーズ 第1回 「エレクトリック・ピュア・ランドと水谷孝」そして「ダムハウス」について

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE