MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

Home > Columns > Stereolab- ステレオラブはなぜ偉大だったのか

Stereolab

ステレオラブはなぜ偉大だったのか

文:イアン・F・マーティン text : Ian F. Martin 翻訳:尾形正弘(Lively Up) Oct 18,2019 UP

1993年から2004年にかけてのステレオラブは、1970年代のデヴィッド・ボウイにも似た活躍を見せ、毎年、新しくて非凡な作品をリリースしていた。個々の作品は単体で見ても優れているのだが、全体として捉えてみると、それがバンドの成長と進化の記録そのものとなって我々を魅了する。

今回のキャンペーンで再発されるのは、グループ(彼らはたびたび自分たちのことを“group”ではなく“groop”と称する。発音は同じだがgroopには「排水溝」という意味がある)がこの期間にリリースした7枚のスタジオ・アルバムだが、この数字だけでは、当時のステレオラブがどれほど旺盛に制作を行っていたかを説明するにはいささか物足りない。7枚のアルバム以外にも、2枚のミニアルバム、2作品からなるコンピレーション・シリーズ『Switched On』、さらには前衛音楽の伝説的バンド、ナース・ウィズ・ウーンドとコラボレーションした数枚のEPが、同じ時期に生み出されているのだから。彼らに関して興味深いのは、結成して活動を始めたときからバンドとしての完全な形態を成立させており、下積みの期間を飛び越えて、そのままデビューアルバム『Peng!』と複数のシングルとEPを完成させ、それを『Switched On』の1作目に繋げたことだ。

ステレオラブの下地となっているのは、1980年代のイギリスおよびアイルランドのギター・ポップ・シーンである。このころティム・ゲインが中心メンバーだった騒々しく反抗的な左翼バンド、マッカーシーに、レティシア・サディエールが加入し、バンドにとって最後の(そして最高傑作である)アルバム『Banking, Violence and the Inner Life Today』が制作された。マッカーシーの歌詞は、1980年代のイギリス左派による政治闘争を主要なテーマとしており、しばしば皮肉を込めて、敵対する政治スタンスをあえて標榜し、そうすることで相手の明らかな不合理や偽善を風刺しようとした。マッカーシーの最後のアルバムを聴けば、そこからステレオラブのサウンドが芽生え始めていたことがわかる。ギターの騒がしい音はわずかに鳴りを潜め、それまで以上に瑞々しく多層的なキーボード主体のサウンドが“I Worked Myself Up from Nothing”などの楽曲に現れている。このアルバムでとりわけ興味深い楽曲が“The Well Fed Point of View”で、マッカーシーの定番とも言える、敵の立ち位置を歌に乗せて風刺する手法を採用している──この曲では、自身の幸福と感情の安寧は本質的に個人の問題だと捉えるべきだと聴き手をけしかける。反面、この世界にある残酷さと不公正さもまた、個人に帰する問題だとしている。マッカーシーが言外に主張しているのは、これらは本来、個人の問題ではなく社会の問題だということだ。こうして培われた思想の中核が、やがてはステレオラブの世界観の根幹を成すことになる。すなわち、個人の問題と、社会的もしくは政治的問題の間には、切り離せない相互関係があるということだ。

ステレオラブが活動を始めたころ、バンドは主にロンドンのミュージシャンたちと交流を持っていた。こうした集まりは「自画自賛の界隈」などと軽蔑されながらも、後のブリットポップに繋がる、何でもありのインディー・ロックシーンを形成していた。当時ステレオラブの周辺には、スロウダイヴ、チャプターハウス、ラッシュなどのシューゲイザーのバンド、またはマッドチェスターの残り火から熱を受け取って早々に名を上げたブラーのようなバンド、そしてシー・シー・ライダー、ガロン・ドランク、ザ・ハイ・ラマズなどの一風変わったパフォーマンスをするバンドなどが存在していた。初期のステレオラブのサウンドには、周囲から受けたさまざまな影響が渾然となっていて、マッカーシーが築いたものをある程度引き継ぎながら、ギターポップとシンセサイザーを組み合わせるだけでなく、シューゲイザーや実験的ポップスの要素も取り入れられている。

他に初期の彼らに多大な影響を与えたのがクラウトロック、とりわけノイ!というバンドの存在だった。1992年に壮大な叙事詩的傑作『Jehovahkill』をリリースしたジュリアン・コープとともに、ステレオラブは90年代初めにクラウトロックへの注目が再燃した際に中心的役割を果たした。その影響が何よりも華々しく描かれているのが、新たに〈Warp Records〉から再発される作品の中でもっとも古い『Transient Random-Noise Bursts with Announcements』である。再発されるアルバムの中でも──そしておそらくステレオラブの全アルバムのなかでも──これがバンドにとってもっとも荒削りで、獰猛なサウンドの作品だ。冒頭の曲“Tone Burst”は素っ気なく始まるが、次第にサウンドは分裂し不協和音の層に溶け込んでいく。それでいて、このサウンドを際立たせるのがサディエールによる幻想的で夢のような歌詞だ。このように粗さと優美さを並列させるスタイルは、次の“Our Trinitone Blast”でも続き、ヴォーカルは前面に出る声と後ろを支える声に分かれ、片方が粗野に歪めば一方が甘く歌うというように、まるでラッシュのようなハーモニーを奏でている。“Golden Ball”では、間断なくかき鳴らされるギターコードとともに、特定の箇所で明らかにテープが途切れたかのような効果が再現され、ノイ!のセカンド・アルバム後半で積極的に採用されているような、故意に曲のスピードを変化させる一筋縄では行かない演出を真似ている。対して“I'm Going Out of My Way”では、ほとんど若者向けのバブルガム・ロックと言っていいようなガレージ・ロックのグルーヴを取り入れ、ひたすら反復を続けることでトランス・ミュージックに似た作用を引き出している。

“Pack Yr Romantic Mind”では、ステレオラブの原動力を示す別の重要な一面が見られる。それは、情念もしくは冷笑主義のどちらかに裏打ちされたサディエールの抑揚のない平板な歌い方と、その後ろに聞こえるメアリー・ハンセンによる「ba ba ba」という歌声との間に生まれる相互作用だ。また、『Transient Random-Noise Bursts』が、ザ・ハイ・ラマズのメンバーだった(その前はアイルランドのインディー・バンド、マイクロディズニーのメンバーだった)ショーン・オヘイガンを正式に迎え入れ、初めてその存在を前面に出して制作されたステレオラブのフルアルバムだという点も見逃せない。この時点で、オヘイガンはギター・ポップからより実験的な方向へという自身の転向を踏まえてバンドを導いていた。そこにはブライアン・ウィルソン、ヴァン・ダイク・パークス、バート・バカラック、フィル・スペクターの他、多くのアーティストの影響があった。アルバムの持つ粗さにもかかわらず、“Pack Yr Romantic Mind”のような曲を聴くと、このころから前衛的なイージーリスニングの影響を受けるようになったことが明白だ。これは後にステレオラブの作品においてますます重要な特色となるものであり、ザ・ハイ・ラマズの1994年のアルバム『Gideon Gaye』にも、オヘイガンによる特色として現れている。それでもやはり、この歌とアルバムの他の曲との共通点をひとつ挙げるなら、それはマントラのような繰り返しに専念していることで、歌詞はひとつのフレーズを途切れることなく何度も復唱するものになっている。

しかしながら、ノイ!が用いたような4ビートのモータリック・サウンドこそが、『Transient Random-Noise Bursts』の特徴としてもっとも強力なもので、楽曲“Jenny Ondioline”の要となっている。歓喜に満ちた18分の歌を構成するのは、のらりくらりと奏でられるキーボード、幾層にも重なるシューゲイザーのギター、反抗的でありながら純真さのあるサディエールの独特な歌声であり、そうした寄せ集めの中で、無限に広がる至福の音が神々しいまでの領域に達している。

『Transient Random-Noise Bursts』がステレオラブのもっとも荒削りなアルバムであるとすれば、1994年の『Mars Audiac Quintet』は、もっとも激しい怒りが歌われているアルバムかもしれない。明るい曲調の“Ping Pong”の軽快なメロディーは、それまでにない都会的なポップ・サウンドで、同時期に日本で渋谷系と呼ばれ始めていたものと類似する。だが、表面的には前向きなこの曲も、歌詞を見ればその様相が一変する。マッカーシーの戦略を引き継いで、語り手は作詞者の真意とは対極にある考え方を持ち、安心させるような口調で、世の中のことで悩むのはやめるようにと聴き手を促す。

「心配いらない 歴史のパターンはもうわかっているから/経済のサイクルがどんなふうに回っていくか/何十年という周期の中で 3つの局面が繰り返し現れる/不況と戦争があっても そこから挽回して元に戻り さらに上を目指していく」

この架空の語り手は、厳しい時代でも悩むことはないと聴き手を煽る。なぜなら「ものごとは自然に良くなっていく」からであり、「凄惨な戦争があって死ぬのは数百万人 だから心配いらない/せいぜい彼らの命とその次の世代の命が失われただけのこと」と強調する。最終的には、社会の現状に対してメンバーたちが抱く怒りや不安が、「悩まなくていい 何も言わず そのままでいい 受け入れて幸せになりなさい」という言葉で封殺されていることを明らかにする。

“Three Longers Later”は、平和を実現するという名目で戦争を行うことの不合理について語る。これは、徴兵制度によって家族から父親を奪われた子供の目を通して描かれる──作詞をしたサディエールの祖国フランスでこの徴兵制度が終了したのは、アルバムリリースの2年後だった(そして本稿執筆時の2019年夏、現大統領エマニュエル・マクロンが何らかの形でこの制度を復活させようと試みている)。このテーマを表現するため、楽曲は童謡と言っていいほど穏やかなメロディーから始まり、やがて爆発してスペースロックと呼ぶにふさわしいクライマックスを迎える。

“Transporte sans Bouger”では、ますます断片化していくように見える世界を嘆く。人びとは空しい「仮想の夢」の中で生き、「隣人のことを知る必要がない」夢の世界で「一定の距離を置いて愛し合う」。1994年には、まだインターネットが人びとの生活に深く浸透していなかったことを考えれば、これは見事な先見性ではないだろうか。徐々に失われていく友好的な地域社会を懐かしむというのは、いくぶん保守的な考え方だ。だが、ステレオラブは左派としてのスタンスにもかかわらず、現在の問題の解決策を探るために過去を振り返ることを決して厭わなかった。

“International Colouring Contest”は、エキセントリックな音楽家で塗り絵帳の制作者であるルチア・パメラの持つ、創造性と宇宙時代的な楽観主義に対する賛辞のようなものだ。曲の冒頭は、ルチア・パメラによる「私の頭の中はアイデアでいっぱい 最高のアイデアを教えてあげる!」という高らかな声のサンプリングから始まっている。ステレオラブは、創造性とは根本的な変革をもたらすものであり、自由の概念と密接につながっているという意識に繰り返し立ち返っている。

反対に、想像力を発揮するための道筋を塞いでしまうものがあれば重苦しく感じられるだろう。“L'Enfer Des Formes”は、冷笑的な態度が、変化をもたらすための行動をどのように阻害するかということを述べ、クラウトロックの影響を受けた“Nihilist Assault Group”は検閲制度と道徳的な危機を題材に、それがいかに批評的な感性を潰えさせ、問題を効率的に対処するためのあらゆる現実的な手段が犠牲になるかということを描く。“Wow and Flutter”とアルバムを締めくくる“New Orthophony”は、現在の状況を避けられないものとして受け入れるのではなく、異議を唱えることの必要性に触れる。

『Mars Audiac Quintet』では、前作同様クラウトロックのリズムセクションの技法に頼っているが、それとともに、紛れもなくアヴァンポップの分野に進んでいる。“Ping Pong”に加えて“L’Enfer Des Formes”もまた、表面的には明るいポップなメロディーを奏で、一方“The Stars Our Destination”と“Des Etoiles Electroniques”では、リズムマシンによる陽気なループ音と、夢幻的なシンセと、絡み合うヴォーカルのメロディーラインが組み合わさって流麗で重層的なサウンドを生み、バンドが進む新たな方向性を示している。

歴史を辿る旅の次なる停車駅は、1996年の『Emperor Tomato Ketchup』だ。本作でこのバンドのサウンドは完全に刷新されているが、それにもかかわらずステレオラブとすぐに認識できる特徴が残っている。前作までと同様、バンドは前進する過程において過去の芸術を参考にしていて、例えばタイトルは日本の劇作家で映画監督の寺山修司による1971年の同名の映画(『トマトケチャップ皇帝』)から取られたものであり、ジャケットのアートワークは1960年代にリリースされたベラ・バルトーク作曲の『Concerto for Orchestra』のジャケットを下敷きにしている。やはりステレオラブにとってお馴染みの要素がアルバムの中核を成しており──繰り返しのリズム、多層的な音作り、あえて外した曲調のポップス、作用しあうサディエールとハンセンのヴォーカル、そしてマルクス主義を遠回しに表現する歌詞──たとえ今作でいっそう洗練された姿へと進化していても、その点は変わっていない。

最初の“Metronomic Underground”では、クラウトロックの中でもファンク寄りの部分、つまりノイ!ではなくカンのようなサウンドを引き出しているが、フレーズの繰り返しとドラムのループが変わらず全体を包みながら、それぞれの歌がモータリックのリズムを刻み続ける。例えばアルバムと同タイトルの楽曲“Emperor Tomato Ketchup”や“Les Yper Sound”では、そこにヴォーカルが融合し、数々のアルバムのなかでもとくに甘美でポップなメロディーが用いられている。華麗な“Cybele's Reverie”はプルースト風の内省によって記憶を巡り、ステレオラブのポップ・ミュージックへの傾倒を踏まえて、より豪華でオーケストラ的な演出を志向している。一方他の場面では、バンドは繰り返しとループ再生を探求する中で、さらに新しくて興味深い手法を発見しており、それはミニマル・ミュージックの“OLV 26”や左右のギターが鏡合わせのように鳴らされる“Tomorrow is Already Here”といった曲で窺える。

歌詞においては、それまでのアルバムと比べてさらに抽象的な世界を探求しているが、このアルバムが個人と社会の関係性というテーマをもっとも明示的に扱っていると言えるかもしれない(少なくとも、ステレオラブの全作品の中で、確実にこのアルバムが一番多く「社会」という言葉を使用している)。“Spark Plug”は、個々の人間やあるいは人間の集団が見せる内なる生命の輝きを、抽象的に捉えるのではなく、実際にあるものとして認識することの重要性を描く。“Tomorrow is Already Here”では、本来は社会に資するために用意された、いくつもの制度が、今では対象を抑圧する元凶となっていることに着目する。対して“Motoroller Scalatron”は、子供向けの歌のように質問と答えを歌詞にするという構成になっていて、社会というものが脆弱な基盤の上に成り立っているのだと語り、現在の社会を維持するには、脆弱な基盤が確かに存在し、そしてそれがしきりに変動しているという考えを共有するしかないと述べる──そして皮肉なことに「言葉の上に築かれた」社会では、我々が言った言葉、あるいは言わないことを選択した言葉が、最後には計り知れない結果を招くことがあるのだとも述べる。

そしておそらく、さらに意義ある変革が、次のアルバム『Dots and Loops』で成された。『Emperor Tomato Ketchup』がリリースされたのと同時期に、シカゴ出身のバンド、トータスが画期的なアルバム『Millions Now Living will Never Die』をリリースし、その少し前にはドイツ生まれのデュオ、マウス・オン・マーズがセカンド・アルバム『Iaora Tahiti』をリリースしていた。3つのグループはいずれも、急速に拡大したにもかかわらず定義が曖昧なままだったポスト・ロックというジャンルのなかで大きな役割を担った。1990年代当時のポスト・ロックを理解するには、ジャーナリストのサイモン・レイノルズの記述がもっとも適しているだろう。「ロックの楽器編成をロックではない用途に使い、ギターはリフやパワーコードを奏でるのではなく、音色や響きを補助するものとして使用される」

コラボレーション相手としてマウス・オン・マーズを選び、トータスのジョン・マッケンタイアをプロデューサーに迎えたことで、『Dots and Loops』はポスト・ロック黎明期の才能がぶつかり合う場となった。ディストーションのかかった電子音で始まり、そのまますぐに軽快なブレイクビーツに続く“Brakhage”では、サディエールが夢のような声で、消費主義の影響を受けて感覚が麻痺してしまうことを嘆く。一方、先行シングルの「Miss Modular」は、ラウンジ・ミュージックの美しい作品で、歌詞は、戯れや神秘、そして目の錯覚といった比喩に言及している──抽象的な比喩表現のために主題がわかりにくいかもしれないが、フランスの状況主義(人の行動は状況によって決定されるところが大きいとする考え方)の先導者ギー・ドゥボールが消費主義を批判したその著作『スペクタクルの社会』にバンドが親近感を抱いていることからも明らかなように、こうした比喩表現が暗示しているのは、人為的なもの──すなわちスペクタクル──が現実と想像、あるいは歴史と終わらない現在の違いを見極める人間の能力を圧倒してしまうときに、社会的な関係性がより広い意味を持つということであるのは確かだろう。このアルバムに特定のテーマがあるとすれば、それは孤立かもしれない。社会や近しい人たちからの孤立だけでなく(そして個人と社会は不可分だとするステレオラブの世界観を考えれば必然的に)自我や自身の感覚からの孤立もまたテーマである。

マッケンタイアとの関係は続く2枚のアルバム、1999年の『Cobra and Phases Group Play Voltage in the Milky Night』と2001年の『Sound Dust』でも続き、その2作には、共同プロデューサーとしてジム・オルークが加わった。『Dots and Loops』に比べればエレクトロニック・サウンドはあからさまではなく、この2枚のアルバムでは、バンドはジャズの影響を取り入れて純然たるアヴァン・ポップの方向に進んでいった。

『Dots and Loops』が孤立の感覚を携えているとすれば、『Cobra and Phases』はバンド史上もっとも希望に満ちた音が鳴るアルバムである。少なくともその要因の一端は、ゲインとサディエールの間に子供が誕生したことにある。それは“People Do it All the Time”ではっきりと言及されていて、歌詞では、創造的営みの混沌たる作用である生命の誕生を大いに喜んでいる。「混沌のなかから創造が生まれる/ひとつの形に結びついて/酒飲みが正気になるように」そして子供は希望で満たされるべき器であると位置づけ「あなたにはのびのびと育ってほしい/私たちが守っている古い考えを蘇らせて」と宣言する。

自由に育っていくことは「古い考えを蘇らせる」ことと両立しなければならないという考え方は、ステレオラブが繰り返してきた、前に進むには振り返ることも必要になるだろうというテーマに対する新しい切り口だ。アルバム全体を通して、(単なる誕生や発見ではなく)生まれ変わりや再発見というイメージが繰り返し登場する。“The Free Design”でサディエールは「願いが届きいつでも復活させられる/私たちにできるのはプロジェクトを再生させるだけ」と歌い、過去のプロジェクトで未完成のまま残されたものがあることをほのめかしている。一方“Puncture in the Radax Permutation”に登場する「孤独に歩む人の形をしたもの」は、それが「五感を取り戻」そうとする姿を通して「自分の歩調を再発見する」ことの象徴として描かれる──新しさとは過去を振り返ることに結びついている、そして、生命のサイクルと生まれ変わりが意味するのは、新しいものは必ず何か古いものと同一であるということだ。そのような考えが、ここで再度強調されているのかもしれない。

『Cobra and Phases』は官能的なアルバムで、最初と最後には愛についての歌が並び、大地と自然のイメージに何度も立ち返っている。本作は、サディエールが女性として生きることをはっきりと単刀直入に歌っている希有な事例であり、フェミニズムのテーマが「Caleidoscopic Gaze」や、クラウトロックにわずかながら回帰した「Strobo Accelleration」で前面に出ている。

『Cobra and Phases』では楽観的な姿勢が念頭にあったが、『Sound Dust』はさまざまな意味でステレオラブのもっとも陰鬱なアルバムで、資本主義に内在する人間性の剥奪と社会の抑圧を扱うテーマに戻っており、“Gus the Mynah Bird”では「自己決定とは事実として存在しなければならない/本来は権利などではない」と断言して、資本主義は偽りの自由を提供し、嬉々として社会の抑圧と結託するのだと示唆する。“Space Moth”で参考にしているのは2人の映画監督、ジャン・ルーシュとエドガール・モランで、彼らによる1960年の映画『ある夏の記録』は、フランスの多様な人々、なかでもとりわけ労働者階級の人々にとっての幸福をテーマに、幸福とは政治と自由に密接な関連があるという考えのもと、戦争、検閲制度、人種の問題に触れ、ホロコーストを痛切に描いている。この歌の「人間はその職に応じて変わる」というフレーズは、再度、資本主義を自由と相反するものとして位置づける。

“Nothing to Do with Me”の歌詞は、イギリスの風刺作家クリス・モリスによる陰気でシュールなコメディーから直接引用されている。そのテレビ番組『ジャム』は、不気味なアンビエントミュージックを短編コメディーに組み合わせ、タブーを破り、ドクターと呼ばれる人種は利他的な人々ではないという描写を用いたことで、イギリスで議論の的となった。モリスが描くドクターは、しばしば混沌の仲介者となる。それは自分たちに頼る人々の信頼を不明確な理由で悪用する権威の象徴である。「私の娘に1ポンドのヘロインを処方したの?」と歌の途中でサディエールは尋ねる。他の箇所では、顧客と依頼人という微妙に異なる立場の関連性に混乱が生じ、ひとりの女が配管工に頼みごとをする。「先日は本当に助かりました/おかげでボイラーが直りました/今度はうちの赤ちゃんを直してくれませんか/あの子はもう3週間も動かないの」どちらの例においても、社会的な関係性が悪用されているのだが、社会的に定められた当事者同士の関係性は、それでもなお形式的には妥当な手続きに守られており、穏やかで理性のある様子を見せることは、他者を威圧する非常識な人間に付け入られることに繋がる。

だが、それ以上に『Sound Dust』は二重性についてのアルバムだと思われる。ステレオラブの曲の多くが、対立する概念を考察して真理に至ろうとする弁証法的アプローチを採用し、2つの対立する勢力や立場に折り合いをつけることを論じていて──命題とそのアンチテーゼがあってこそ、総合的な判断ができるということだ──その構造が変わらず存在する。「Baby Lulu」の歌詞は「両極端なものは一致していた/即興を奏でる/合理的にそして詩的に/すぐに矛盾を見極めながら」と述べている。そしてこれは、バンドにとって、これまででもっとも率直に邪悪という概念に向き合ったアルバムだということでもある。「Naught More Terrific than Man」の歌詞に「ふたつの対極点が人の歩みを導く」とあり、対極点のうちのひとつが邪悪そのものとして描かれる。そして「Suggestion Diabolique」では、邪悪の概念が明らかに聖書を意識した内容で表される。メロディーの華麗さや温かさや美しさは、歌詞の暗さや厳粛さと相まって、アルバムのテーマと同様の二重性を有している。

このような特徴は、アルバムの音楽的な構成にも反映されており、多くの曲がふたつのパートで構成されている。曲の前半と後半では、メロディーもアレンジも、まったく別のものが展開される。もっとも際だった事例が、楽しげな“Captain Easychord”で、生と死のサイクルというテーマに戻り、それを突き詰めた結果、もっとも基本的な息を吸って吐くという行為のサイクルによってそのテーマを表現している。

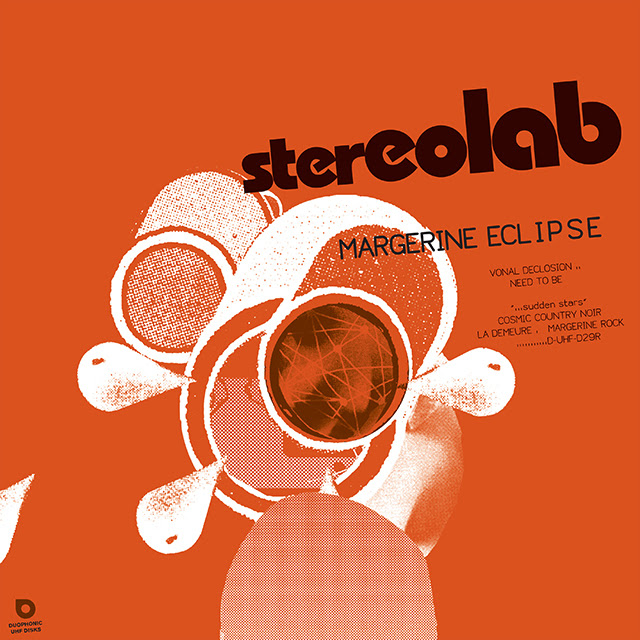

『Sound Dust』はメアリー・ハンセンが参加した最後のアルバムとなった。ハンセンが翌年、交通事故で他界したからだ。今回の再発キャンペーン最後のアルバムとなる2004年の『Margerine Eclipse』には、ハンセンに捧げるという側面がある。楽曲“Feel and Triple”では直接別れに言及し、“Need to Be”では、今あるものを認めるために、痛みや寂しさや死への恐れを受け入れることの必要性を語り、そして“…Sudden Stars”では、愛に向き合って喪失の悲しみを尊重することを伝える。

当時のヨーロッパやアメリカの政治状況もまた、アルバムのあちらこちらに影を落としている。それは、アフガニスタンやイラクでの戦争、自分たちの中にムスリムという「他者」がいることで具体化したテロの恐怖の増大、そしてますます過度になる国家の監視という姿で現れている。“La Demeure”はこの他者への恐怖を描き、“Bop Scotch”は、我々は自由と安全を天秤にかけられるのかという問いかけを論じる。

死と恐怖が影を落としているにもかかわらず(あるいは、だからこそと言うべきか)『Margerine Eclipse』はステレオラブのもっとも明るいアルバムのひとつでもあり、また、間違いなくもっともファンク寄りのアルバムで、豊かで濃密なシンセとベースのサウンドが派手に鳴らされながら推進する。そしてこれはもっとも明確に愛を謳ったアルバムであり、最後の曲“Dear Marge”では愛することと学ぶことを関連づけていて、反面、愛と共感が欠けていれば人は学ぶことも成長することもままならないという含みを持たせている。

『Sound Dust』と同様、弁証法的な構成が『Margerine Eclipse』の基礎を作っている。『Margerine Eclipse』では、ミックス時にすべての楽器の音が極端に右か左にパンをした状態で配置されていて、左右それぞれのサウンドが独立して成立していながら、それでいて同時に聴いたときに2つが統合されるように設計されている。

この期間に製作された作品を聴いた上で改めて問うてみよう。ステレオラブにとって、バンドとして本当に重要なことは何だろうか?

このバンドを理解するためのひとつの手段は、同じ時代の見地から彼らを探ってみることだ。この7枚のアルバムは、ソビエト連邦の崩壊に始まり、2001年9月11日にワールドトレードセンターが攻撃され冷戦後のアメリカにもはや敵はいないという意識が粉砕された10年間と、密接に重なっている。

経済学者フランシス・フクヤマによって「歴史の終わり」と表現されるこの時代には、社会全体が持つ大規模な想像力が通用しなくなったという特徴がある。20世紀に繰り広げられた巨大なイデオロギー同士の闘争は終焉を迎え、自由資本主義が勝利を収めた。それに取って代わるものは存在しなかった。そして評論家マーク・フィッシャーが「資本主義リアリズム」と呼んだ考え方が浸透した結果、さまざまな未来の展望が示されても、すべてが必ずしも「二番煎じ」とは限らなかったにもかかわらず、それらを一律に実現不可能なものとして扱う風潮が生まれた。

この考え方こそ、ステレオラブが繰り返し非難してきた敵そのものだ。『Mars Audiac Quintet』収録の“Wow and Flutter”の歌詞が、それをもっとも明快に表現している。

「IBMはこの世界とともに誕生したのだと思っていた/アメリカの旗は永遠に漂うのだろう/冷淡な敵対者は早々にいなくなった/資本家はこれからもついていかなくてはならない/それは永遠でも不滅でもない/そう きっと変わっていくだろう/それは永遠でも不滅でもない/化石のような法律なのだから」

資本主義リアリズムは人の想像力に制限を加えることで、狡猾で抑圧的な力を持つ。そしてステレオラブにとって、これを克服するには、意識を高く持ち、独創的な(そして夢想的な)精神を発揮するより他にない。状況主義の誕生と、1968年のパリで起こった五月革命(学生たちの運動に端を発したフランスの社会的危機で、世界中の社会運動に多大な影響をもたらした)で示されたように、個人の創造性と構想力が発揮される類まれな瞬間に、社会にショックを与えて、ひとつのサイクルを終わらせ、世のなかを新しい段階へ引き上げることができる。ちょうど『Emperor Tomato Ketchup』のジャケットに描かれた螺旋のように、変わらず周回を続けながらも、常に空に向かって上昇するのである。この意味で、ステレオラブの展望には、フィッシャーが不慮の死の直前まで展開していた思想や、彼が「アシッド共産主義」と称した概念と共通する部分がある。この意味における共産主義とは、資本主義者の自己満足に向かって投げ込まれた修辞上の爆弾であり、20世紀の共産主義体制の再現ではない。そもそもスターリンの抑圧体制は、フィッシャーやステレオラブのような人びとにとっては常に恐怖の対象だった。むしろ彼らは五月革命の子供世代(フィッシャーとサディエールは共に1968年生まれ)であり、アシッド・ハウス全盛のときに成人を迎えた──両者の展望は、地域社会に分散した自発的な活動の影響を受けている。「アシッド共産主義」の「アシッド」という名称は幻覚剤から取られたものかもしれないが、その真の意味は、言葉が持つ以上のものがある。アシッドすなわちLSDは、意識を上昇させ新たな段階に引き上げる行為の同義語となっており、さらにその背後には実験や探求という意味合いも込められるようになった。これはまた、ステレオラブが新たな表現に至るために再三にわたって創造性を引き出そうとしていることと深く合致している。そして『Mars Audiac Quintet』では明確にこのテーマに向き合っており、“Three-Dee Melodie”にはこう歌われている。

「存在することの価値は/宗教やイデオロギーによって与えられるのではない/意味があろうとなかろうとそれは崖っぷちに出現する/それこそが創造的に生きることで得られる唯一の力」

では、フィッシャーが語っていたように「未来が取り消された」とき、それをもう一度、発見し直すにはどうすればいいだろうか? ひとつの手段は過去に目を向けることだ。

取り消された未来の幻影は、現在を生きる我々を苛む。その姿は、あるときはノスタルジーとなり、あるときは俗悪なものとなり、あるときは我々の充実感を潰えさせるほどの威力を持ったままで現れる。フィッシャーは、過去と現在が共存する不自然なこの状況を「憑在論」と呼んだが、前を向く人々にとっては、このように未来が失われたことは、一旦退いた上で新たな道を探して前進するための好機となる。1960年代のヒッピーによるカウンター・カルチャー、1968年の五月革命、昔のサイエンスフィクション作家たちが描いた理想郷の姿というように──ステレオラブの美的価値観は、彼らが過去を掘り進め、独自の理想郷への道を開いていることから、ときに「レトロフューチャー」と評される。初期におけるクラウトロックへの執着もまた、過去の光景を想像しながら再訪し、その先に何か新しいものを追い求めることで、未来に目を向けるためのものである──この結果として、図らずもポスト・ロックが誕生する一助となったのである。

往々にして革命の実体は幻影のようなものだ。なぜなら、それは現実となるまでは物質的な姿を持たない概念として存在し、静かに現在の体制を脅かしていくからだ。よく知られているように、マルクス自身が共産主義を「ヨーロッパに取り憑いた」亡霊であると表現したが、この場合のより適切な描写は、1819年のピータールーの虐殺(選挙法の改正を求めてマンチェスターの広場に集まった群衆を騎兵隊が鎮圧しようとして多くの死傷者を出した事件)で犠牲になった人びとについて急進的詩人パーシー・ビッシュ・シェリーが述べた「彼らの墓所からは輝かしい幻が飛び出してくるだろう」という表現だろう──果たされなかった革命は、それでもなお、いずれ蘇ってその目的を達成するかもしれないという脅威を孕んでいる。1960年代に成し得なかった革命の数々は、取り消されたその他のあらゆる未来と同じように、ステレオラブの楽曲に息づいている。

ステレオラブの作品で中核となる弁証法的手法があるとするならば、彼らは問題を解決するために、常に意識を高めて創造性を抑制しないという方向性を目指しているように見受けられる──想像や創作から何か新しいものが生まれる希有な瞬間、それはより自由な世界へ突き進むための革命的手段として世界に登場する。そこに立ちはだかるのが、世界はともすると同じパターンやサイクルを繰り返してしまうという事実だ。例えば、不況で経済が落ち込み戦争が起こり回復していくように、愛が花開いて枯れていくように、そして死と再生のサイクルがあるというように。ステレオラブの音楽は、それ自体がこの世界に呼応している。その形式は繰り返しによって定められながら、創造的発見が生まれる類まれな瞬間に前進して新しいパターンを獲得する。あるいは別の言葉で表すなら、これはまさにアルバム『Dots and Loops』のタイトルのごとく「点とループ」が織りなすシンフォニーだ。

Stereolab in the years 1993 to 2004 were like David Bowie in the 1970s in that every year saw them release something new and extraordinary, each a wonderful record in its own right, but taken together adding up to a fascinating document of a band’s growth and development.

The current batch of re-releases encompasses the seven studio albums the group (or “the groop”, as they often referred to themselves) released over that period, although this slightly understates just how productive Stereolab were at that time, with two mini-albums, two volumes of their excellent “Switched On” compilation series, and a couple of collaboration EPs with avant-garde legend Nurse with Wound also falling within the same timeframe. What’s interesting about them is that they start off with the band fully-formed in their first incarnation, skipping over the period of finding their feet that that defined their debut album “Peng!” and the singles and EPs that made up the first “Switched On” compilation.

Stereolab’s background lies in the British and Irish 1980s guitar pop scene, with Tim Gane having been a key member of the jangly and defiantly left-wing McCarthy, joined by Laetitia Sadier for their last (and best) album “Banking, Violence and the Inner Life Today”. McCarthy’s lyrics mostly focused on the political struggles of the 1980s British left, often ironically adopting the stance of political enemies in order to satirise their perceived absurdities or hypocrisies. It was on that final McCarthy album that you start to hear the early murmurs of Stereolab, with the band dialing the guitar jangle back slightly in favour of a more lush, layered, keyboard-based sound on songs like “I Worked My Way Up from Nothing”. A particularly interesting song on this album is “The Well Fed Point of View”, which takes the standard McCarthy approach of satirically vocalising their enemy’s position – in this case, a voice encouraging listeners to see their happiness and emotional wellbeing as essentially individual issues, with the flipside of that being that the cruelty and injustice of the world is also the problem of individuals. McCarthy’s implied message, that these are actually social rather than individual issues, lays down a key idea that would become a key part of Stereolab’s worldview: the inseparable interrelationship between the personal and the social or political.

In Stereolab’s early days, they were connected to a cluster of musicians in London, known cynically as “the scene that celebrates itself”, as well as the eclectic pre-Britpop indie scene. Around them at that time were shoegaze bands like Slowdive, Chapterhouse and Lush, bands like Blur, who had risen to early fame heated by the dying embers of the Madchester scene, and oddball acts like See See Rider, Gallon Drunk and The High Llamas. The early Stereolab sound shows a mixture of these influences, picking up in part from where McCarthy left off, combining guitar pop with synthesisers, but also drawing on elements of shoegaze, and experimental pop.

The other big influence in these early days is krautrock, and Neu! in particular. Along with Julian Cope, whose epic cosmic masterpiece “Jehovahkill” came out in 1992, Stereolab were key figures in the revival of interest in krautrock that bloomed in the early ’90s. It’s this influence that and the expresses itself most spectacularly on the oldest of the new Warp Records re-releases, “Transient Random-Noise Bursts with Announcements”. Of all the re-releases – perhaps of all Stereolab albums – this is the band’s rawest and most sonically brutal. The opening song, “Tone Burst” begins simply, but gradually dissolves into layers of sonic discord, but set against this are Sadier’s deamily romantic lyrics. That juxtaposition of harsh and sweet continues on “Our Trinitone Blast”, with the vocals pinging back and forth, one part harsh and distorted and the other sweet, Lush-like harmonies. “Golden Ball”, with its relentless, clanging guitar chord, fakes an apparent tape breakdown at one point in a way that echoes the frequent, deliberately awkward speed-changes in side two of Neu!’s second album. Meanwhile, “I’m Going Out of My Way” takes a garage rock, almost bubblegum, groove and turns it into something trancelike through sheer repetition.

“Pack Yr Romantic Mind” showcases another key aspect of the Stereolab dynamic: the interplay between Sadier’s plain vocal delivery, uninflected by either passion or cynicism, and Mary Hansen’s backing “ba ba ba”s. It’s telling as well that “Transient Random-Noise Bursts” is Stereolab’s first full album to feature Sean O’Hagan of The High Llamas (formerly of Irish indie band Microdisney) as an official member. O’Hagan was at this point navigating his own transition from guitar pop to something more experimental, drawing on the influences of Brian Wilson, Van Dyke Parks, Burt Bacharach, Phil Spector and more. Despite the album’s harshness, tracks like “Pack Yr Romantic Mind” reveal the beginnings of an avant-garde easy listening influence that would become an increasingly important feature of Stereolab’s work, as well as O’Hagan’s on The High Llamas’ 1994 album “Gideon Gaye”. Nonetheless, one thing the song has in common with the rest of the album is its dedication to mantric repetition, with the lyrics just a single phrase repeated over and over again in a loop.

The motorik sounds of Neu! are what most powerfully define “Transient Random-Noise Bursts” though, and the centrepiece is Jenny Ondioline, a joyous 18 minutes of droning keyboard, layered shoegaze guitars, and Sadier’s uniquely disaffected-yet-wide-eyed vocals that punches through pastiche into a heavenly realm of cosmic sonic bliss.

If “Transient Random-Noise Bursts” is Stereolab’s harshest sounding album, 1994’s “Mars Audiac Quintet is perhaps their lyrically angriest. On the upbeat “Ping Pong”, the bouncy melody parallels the sophisticated emerging pop sounds that were starting to get called Shibuya-kei in Japan at this time, but the song’s superficial positivity is undercut by its lyrics. Following the McCarthy playbook, the narrator adopts a position opposed to the author’s true intentions, taking the reassuring tone of someone urging the listener to stop worrying about the world.

“It's alright 'cause the historical pattern has shown / How the economical cycle tends to revolve / In a round of decades, three stages stand out in a loop / A slump and war, then peel back to square one and back for more.”

The fictional narrator urges the listener not to worry about bad times because “things will get better naturally”, noting that “There's only millions that die in the bloody wars, it's alright / It's only their lives and the lives of their next of kin that they are losing,” and finally revealing their own anger and disquiet at seeing the status quo questioned by declaring, “Don't worry, shut up, sit down, go with it and be happy.”

“Three Longers Later” talks about the absurdity of waging war in order to achieve peace through the eyes of a child seeing their father ripped away from his family by military conscription – a system that wouldn’t be ended in lyricist Sadier’s home country of France until two years later (and which current president Emile Macron is, at the time of writing in summer 2019, trying to bring back in some form). It does this over a melody that begins quietly, almost like a nursery rhyme, and then explodes into a spacerock climax.

“Transporte sans Bouger” laments a world that seems to be becoming increasingly atomised, with people living in a lonely “virtual dream” with “no need to know your neighbour”, in which we “make love at a distance”. Given that the internet hadn’t penetrated people’s lives very deeply in 1994, this seems prescient. It is also rather conservative in its yearning for an increasingly lost sense of neighbourly community, but despite their leftist outlook, Stereolab were never averse to looking back to the past to find solutions to the problems of the present. “International Colouring Contest” is a tribute of sorts to the creativity and space-age optimism of eccentric musician and colouring book creator Lucia Pamela, who is sampled at the beginning of the song exclaiming, “I’m so full of ideas, and here’s a good one!” Repeatedly, Stereolab return to the notion that creativity is a fundamentally revolutionary act, and one inextricably bound up with the idea of freedom.

The inverse of that is that anything that closes off routes through which the imagination can travel is oppressive. “L’Enfer Des Formes” notes the way cynicism kills action for change, while the krautrock-influenced “Nihilist Assault Group” is concerned with censorship and moral panic, and how that annihilates critical sensibilities at the expense of effectively dealing with problems in any real way. “Wow and Flutter” and the closing “New Orthophony” both touch on the need to challenge rather than accept as inevitable the way things currently are.

While “Mars Audiac Quintet” relies on a similar toolbox of krautrock rhythms as its predecessor, things are also clearly moving forward into avant-pop territory. In addition to “Ping Pong”, “L’Enfer Des Formes” is another superficially upbeat pop melody, while “The Stars Our Destination” and “Des Etoiles Electroniques” both combine bubbly rhythm machine loops, dreamy synths and intertwining vocal lines into a smooth, layered sound that points a new way forward for the band.

The next stop on that journey was 1996’s “Emperor Tomato Ketchup” which completely blew apart the band’s sound while remaining instantly recognisable as Stereolab. As before, there are nods to the past in how the band move forward, with the title being drawn from Japanese playwright and director Shuji Terayama’s 1971 film of the same name and the cover artwork being based on a 1960s release of Bela Bartok’s “Concerto for Orchestra”. Nevertheless, the familiar Stereolab elements still make up the core of the album – the repetitive rhythms, the layered production, the off-kilter pop tunes, Sadier and Hansen’s vocal interplay, and the obliquely Marxist lyrical themes – albeit now developed into something far more sophisticated.

The opening “Metronomic Underground” draws from a funkier side of krautrock, more Can than Neu!, but still wrapped up in repetition and looping rhythms, while the songs that retain motorik rhythms, like the title track and “Les Yper Sound” marry it with vocal lines that employ some of the albums sweetest pop melodies. The gorgeous “Cybele’s Reverie” is a Proustian meditation on memory, that takes Stereolab’s pop inclinations in a more lushly orchestral direction, while elsewhere the band find ever more new and interesting ways to explore repetitions and loops, from the minimal “OLV 26” to the mirrored guitar clang of “Tomorrow is Already Here”.

Lyrically, it explores more abstract places than previous albums, but it’s perhaps the album most explicitly concerned with the relationship between the individual and society (certainly it’s the album in Stereolab’s catalogue that uses the word “society” most). “Spark Plug” is concerned with the importance of recognising the innate spark of life in an individual or collective group rather than viewing them in the abstract. “Tomorrow is Already Here” deals with institutions originally set up to serve society, now become something oppressive. Meanwhile, “Motoroller Scalatron”, with its children’s song-like question-and-answer structure talks about the fragile basis on which society is constructed, maintaining its existence only on a shared agreement that it exists, and constantly in flux – as well as the irony that, in a society “built on words”, the words we say, or choose not to say, can end up having huge consequences.

Perhaps an even more significant shift came with the next album, “Dots and Loops”. At around the same time that “Emperor Tomato Ketchup” was being released, Chicago-based Tortoise were releasing the landmark “Millions Now Living will Never Die” and German duo Mouse On Mars had recently released their second album “Iaora Tahiti”. All three were key acts in the burgeoning but nebulous genre of post-rock, which at this point in the 1990s can best be understood using journalist Simon Reynolds’ description as, "using rock instrumentation for non-rock purposes, using guitars as facilitators of timbre and textures rather than riffs and power chords."

Bringing in Mouse on Mars as collaborators and Tortoise’s John McEntyre as producer, “Dots and Loops” was a collision of early post-rock talent. Opening with a burst of electronic distortion, it swiftly moves into the skittering breakbeats of “Brakhage”, Sadier dreamily bemoaning the narcotising effects of consumerism. Lead single “Miss Modular”, meanwhile, is a beautiful slice of lounge pop with lyrics touching on imagery of games, mystery and tricks of the eye – abstract imagery with an opaque subject, but one that, for a band undoubtedly familiar with French situationist leader Guy Debord and his consumerist critique “The Society of the Spectacle”, surely hints at wider social relevance in the way the artificial – the spectacle – overwhelms our ability to discern a difference between reality and representation, history and endless present. If there’s a particular theme of the album, it might be that of alienation, not only from society and people close to you, but also (and necessarily given the way the individual and society are inextricable in Stereolab’s worldview) alienation from the self and one’s own feelings.

The collaboration with McEntyre continued over the next two albums, 1999’s “Cobra and Phases Group Play Voltage in the Milky Night” and 2001’s “Sound Dust”, with Jim O’Rourke joining as co-producer on both albums. Less explicitly electronic than “Dots and Loops”, these two albums see the band picking up on its jazz influences and advancing with them into pure avant-pop.

If “Dots and Loops” carried a sense of alienation, “Cobra and Phases” is the band’s most hopeful sounding album, with at least part of that coming from the birth of Gane and Sadier’s child, explicitly referenced on “People Do it All the Time”, which revels in the birth as a chaotic act of creation, “Out of chaos, a creation / Binding into one form / Lucid drunkenness” and positions the child as a vessel of hope, declaring, “I want you free when you grow, boy / Revive the old idea that we carry.”

The idea that growing up free should go together with “reviving an old idea” is a new angle on Stereolab’s recurring theme that moving forward may require looking back. Throughout the album, images of rebirth and rediscovery (rather than simply birth and discovery) keep cropping up. On “The Free Design” Sadier sings “The request is here ready to resurrect / What else can we do but recover the project” hinting at a past project left unfinished, while the “lonely walker humanoid” of “Puncture in the Radax Permutation” is described as “rediscovering your own pace” as it tries to “repossess the senses” – the idea of newness being linked to going back to something, and perhaps also of the cycle of life and rebirth meaning that everything new is something old just come round again.

“Cobra and Phases” is a sensual album, opening and closing with songs about love, and constantly returning to images of earth and nature. It’s also a rare example of Sadier singing explicitly and directly about being a woman, with feminist themes coming to the fore in “Caleidoscopic Gaze” and krautrock slight return “Strobo Accelleration”.

With the positive attitude of “Cobra and Phases” in mind, “Sound Dust” is in many ways Stereolab’s darkest album, returning to themes touching on the dehumanisation and oppression inherent in capitalism in songs like “Gus the Mynah Bird”, which declares “Self determination should be a fact / not essentially a right,” and suggests that capitalism offers false freedom, and will happily collude with oppression. “Space Moth” references the filmmakers Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, whose 1960 film “Chronicle of the Summer” deals with the subject of happiness among various, mostly working class, people in France, touching on war, censorship, race, and poignantly the Holocaust, with the idea that happiness is closely linked to politics and freedom. The line in the song “L'homme est réduit à son travail” – “man is reduced to his job” – again positions capitalism as antagonistic to freedom.

The song “Nothing to Do with Me” takes its lyrics directly from the dark, surreal comedy of British satirist Chris Morris, whose TV show “Jam” combined eerie ambient music with comedy sketches and was controversial in the UK for breaking the taboo against portraying doctors as less than altruistic people. Morris’s doctors were often agents of chaos: figures of authority who abused the trust of people who relied on them, for opaque reasons. “Did you prescribe my daughter a pound of heroin?” asks Sadier at one point in the song. Elsewhere, the relationship between customer and client is turned on its head as a woman asks a plumber, “You did such a great job / With the boiler last time / Please can you mend my baby / He hasn't moved for three weeks.” In both instances, a social relationship is being abused, but the socially defined relationships between the participants are still followed in a formally proper way, the form and appearance of calm rationality put into the service of the terrifying and absurd.

More than this, though, “Sound Dust” feels like an album about duality. Many of Stereolab’s songs are dialectic in that they deal with reconciling two opposing forces or positions – the thesis and antithesis birthing a synthesis – and that structure is still present here. “Baby Lulu” delivers the line “extremes reconciled / improvisation / rational and poetical / summing up contradictions”. It’s also the most direct the band ever were about the notion of evil, referencing it as one of the “two poles guiding his step” in “Naught More Terrific than Man”, and giving it an explicitly Biblical face in “Suggestion Diabolique”. The lushness, warmth and beauty of the melodies works in a similar dualistic way with the darkness or gravity of the lyrics.

This is reflected in the musical structure of the album too, with many of the songs having a two–part structure, where the first and second half of the song follow quite different melodies and arrangements. The most striking example is the joyous “Captain Easychord”, which returns to the theme of the life and death cycle, boiling it down to its most basic representation in the cycle of inhaling and exhaling breath.

“Sound Dust” was the final album to feature Mary Hansen, who was killed in a road accident the following year. The last album of this current batch of re-releases, 2004’s “Margerine Eclipse” is in part a tribute to Hansen, with the song “Feel and Triple” a directly addressed farewell, “Need to Be” talking about the need to embrace pain, loneliness and fear of death in order to recognise the now, and ‘…Sudden Stars’ dealing with embracing love and respecting loss.

The political situation in Europe and America at the time also hangs over parts of the album, in the shape of the wars in Afghanitan and Iraq, rising fear of terrorism embodied in the “other” of the Muslim in our midst, and increasingly intrusive state surveillance. “La Demeure” references this fear of the other, while “Bop Scotch” deals with the question of whether we can trade freedom for security.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the death and fear hanging over it, “Margerine Eclipse” is also one of Stereolab’s most upbeat albums, and certainly their funkiest with its rich, thick, squelchy synth and bass sounds. It is the album that most explicitly addresses love, with the closing “Dear Marge” tying love up with learning, with the implied flipside that lack of love or empathy prevents us from learning or growing.

Like “Sound Dust” there is a dialectical structure underlying “Margerine Eclipse”, with the album being mixed with all the instruments panned to the extreme right or left, with each channel designed to work either independently or as a synthesis of the two made when both are listened to together.

After listening over this span of work, what is Stereolab really about as a band though?

One way to make sense of the band is to look at them through the prism of their times. These seven albums closely overlap with the ten-year period after the fall of the Soviet Union and the aftermath of the September 11th, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center that shattered America’s sense of post-Cold War invulnerability.

This period, described by Francis Fukuyama as “The End of History”, was characterised by a shutting down of the public imagination on a mass scale. The struggle between great ideological movements of the 20th Century was over and liberal capitalism had won: there was no alternative. A mindset took hold of what the critic Mark Fisher called “capitalist realism”, which made any vision of the future that didn’t essentially amount to “more of the same” seem impossible.

This mindset is the enemy against which Stereolab constantly rail. The lyrics to “Wow and Flutter” from “Mars Audiac Quintet” express it most clearly:

“I thought IBM was born with the world / The US flag would float forever / The cold opponent did pack away / The capital will have to follow / It's not eternal, imperishable / Oh, yes it will go / It's not eternal, interminable / The dinosaur law.”

The limits capitalist realism place on the imagination are what make it such an insidiously oppressive force, and one that, for Stereolab, can only be overcome by the lifting of consciousness and the opening up of the creative (and the romantic) mind. As with the situationists and the 1968 Paris Spring, unique moments of individual creativity and imagination can jolt society out of one of its cycles and elevate it to a new level, like the spiral on the cover of “Emperor Tomato Ketchup”, ever-circling but always reaching skyward. In this sense, Stereolab’s vision shares something in common with the ideas Fisher was developing before his untimely death, and which he referred to as “acid communism”. In this sense, communism is really functioning as a rhetorical bomb thrown into the midst of capitalist complacency rather than a recreation of the communist regimes of the 20th century. The repressiveness of Stalin would have been a horror to people like Fisher and Stereolab: rather they were children of the Paris Spring (both Fisher and Sadier were born in 1968), who came of age at the height of acid house – both visions of decentralised, spontaneous, communal action. The “acid” of “acid communism” may take its name from psychedelic drugs, but its true meaning perhaps lies more in what it represents. Acid or LSD has become synonymous with the act of elevating consciousness to a new level, with an underlying meaning of experimentation and exploration. This again locks in very well with Stereolab’s repeated invocation of creativity as a route to revelation. Again, “Mars Audiac Quintet” tackles the theme explicitly, this time on “Three-Dee Melodie”:

“The meaning of existence / Can't be supplied by religion or ideology / The sense or non-sense that will emerge from the precipice / Is only the impact of a creative activity”

So when, as Fisher put it, “the future has been cancelled”, how do we rediscover it anew? One way, is to look to the past.

The ghosts of cancelled futures haunt the present, sometimes as nostalgia, sometimes as kitsch, sometimes as something that still has the power to jolt us out of our complacency. Fisher referred to this uneasy coexistence of past and present as “hauntology”, but for those of us looking ahead, these lost futures can provide opportunities to step back and find a new route forward. The hippy counterculture of the 1960s, the 1968 Paris Spring, the utopian visions of old science-fiction authors – Stereolab’s aesthetic is often described as “retro-futurist” because of the way they mined the past for routes towards their own utopia. Their early obsession with krautrock is another way of looking to the future by revisiting past visions of what it might be like and pursuing those lines towards something new – in this case, helping to bring post-rock into existence in the process.

Revolution often takes the form of a ghost because, before it can become real, it will exist as an idea without corporeal form, silently threatening the status quo. Marx himself famously described communism as a spectre that “is haunting Europe”, but more pertinent in this case might be the radical poet Percy Bysshe Shelley’s depiction of the victims of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre as “graves from which a glorious Phantom may burst” – an unfinished revolution that nevertheless threatens to return and complete its work. The failed revolutions of the 1960s live on in Stereolab’s songs, as do all the other cancelled futures.

If there is a central dialectic process at work with Stereolab, the direction they seem to be trying to resolve it in always leans towards a kind of raised consciousness and unrestrained creativity – unique moments of imagination and creation bringing something new into the world as a revolutionary means towards pushing forward into a place of greater freedom. Against that lies a tendency of the world to fall into repeating patterns and cycles, whether they be destructive cycles of economic depression, war and recovery, the blooming and dying of love, or the cycle of death and rebirth. Stereolab’s music itself parallels this, its own forms defined by repetition, driven forward into new patterns by unique moments of creative revelation – or to put it another way, it is a symphony of “dots and loops”.

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

COLUMNS

- Columns

スティーヴ・アルビニが密かに私の世界を変えた理由 - Columns

6月のジャズ- Jazz in June 2024 - Columns

♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう - Columns

5月のジャズ- Jazz in May 2024 - Columns

E-JIMAと訪れたブリストル記 2024 - Columns

Kamasi Washington- 愛から広がる壮大なるジャズ絵巻 - Columns

♯6:ファッション・リーダーとしてのパティ・スミスとマイルス・デイヴィス - Columns

4月のジャズ- Jazz in April 2024 - Columns

♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く - Columns

3月のジャズ- Jazz in March 2024 - Columns

ジョンへの追悼から自らの出発へと連なる、1971年アリス・コルトレーンの奇跡のライヴ- Alice Coltrane - Columns

♯4:いまになって『情報の歴史21』を読みながら - Columns

攻めの姿勢を見せるスクエアプッシャー- ──4年ぶりの新作『Dostrotime』を聴いて - Columns

2月のジャズ- Jazz in February 2024 - Columns

♯3:ピッチフォーク買収騒ぎについて - Columns

早世のピアニスト、オースティン・ペラルタ生前最後のアルバムが蘇る- ──ここから〈ブレインフィーダー〉のジャズ路線ははじまった - Columns

♯2:誰がために音楽は鳴る - Columns

『男が男を解放するために』刊行記念対談 - Columns

1月のジャズ- Jazz in January 2024 - 音楽学のホットな異論

第2回目:テイラー・スウィフト考 - ――自分の頭で考えることをうながす優しいリマインダー

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE