MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

Home > Columns > 不屈のペーター・ブロッツマン- The indomitable Peter Brötzmann

何年もの間、ペーター・ブロッツマンの来日は、四季の巡りのように規則的で、晩秋の台風が通り過ぎていくかのように感じられたものだった。彼には、どこか自然で率直なところがあり、それは嵐のように吹き荒れる叫びが、やがては柔和でブルージーな愛撫へと代わるような彼が創りだすサウンドのみならず、その存在自体についていえることだった。セイウチのような口髭、シガーをたしなむその印象的な風貌は人目を引き、無意味なことを許さない生真面目なオーラを纏っていた。ブロッツマンは、侮辱などは一切甘受しなかった。

6月22日に82歳で死去したドイツのサクソフォン及び木管楽器奏者は、そのキャリアの多くの時間を、無関心とあからさまに辛辣な批評との闘いに費やした。若い頃には、ヨーロッパのジャズ界の伝統的なハーモニーと形式の概念を攻撃して憤慨させ、同時代のアメリカのアルバート・アイラ―やファラオ・サンダーズたちよりも先の未知の世界へと自らの音楽を押し進めた。ドン・チェリーが命名した「マシン・ガン」というニックネームは、1968年に発表したブロッツマンの2枚目のアルバムのタイトルとなり、フリー・ジャズの発展を象徴する記念碑的な作品となった。

最初は自身の〈BRÖ〉レーベルから300枚限定で発売されたこのアルバムは、ヴェトナム戦争やヨーロッパを揺さぶった大規模な抗議活動など、当時の爆発的な雰囲気の世相を反映していた。アルバムではベルギーのピアニスト、フレッド・ヴァン・ホーフ、オランダのドラマー、ハン・ベニンクやイギリスのサクソフォン奏者エヴァン・パーカーを含む、世界のミュージシャンたちがキャスティングされていたが、『マシン・ガン』は明確にドイツという国の、ナチスについての恥とトラウマという過去を標的にしていたようだ。

「おそらく、それが、このような音楽のドイツとそのほかのヨーロッパの演奏の響きに違いをもたらしているのかもしれない」とブロッツマンは、亡くなる数週間前の6月初旬にディー・ツァイト紙のインタヴューで語っている。「ドイツの方が常に叫びに近くて、より残忍で攻撃的だ」

その叫びは、今後何十年にもわたり響き続けるだろう。その一方、彼のフリー・ジャズの同僚たちは、若くして死んだか、年齢とともに円くなっていったのに対し、ブロッツマンは以前と変わらぬ白熱した強度での演奏を続けた。それが彼の健康に相当な負担となり、最後の数十年には、生涯にわたって強く吹き続けたことで、呼吸器に問題を抱えるようになった。2012年のザ・ワイヤー誌のインタヴューでは「4人のテナー・サックス奏者のように響かせたかった……。『マシン・ガン』で目指したことを、いまだに追いかけている」と語っていた。

そのサウンドは、直感的な反応を引き起こすようなものだった。2010年10月に、ロンドンのOtoカフェで彼のグループ、フル・ブラストを聴きに、彼についての予備知識のない友人を連れていった際、演奏開始の瞬間に彼女が物理的に後ずさりをした光景を思いだす。

しかし、ブロッツマンの喧嘩っ早い大男という風評は、彼の物語のほんの一部に過ぎない。独学で音楽を始め、最初はディキシーランドやスウィングを演奏し、コールマン・ホーキンスやシドニー・ベシェなどのサクソフォンのパイオニアたちへの敬愛を抱き続けた。それらの影響は、『マシン・ガン』でも聴くことができる。ジャン=バティスト・イリノイ・ジャケーのホンキーなテナーや、初期のルイ・アームストロングの熱いジャズなどもそうだ。その凶暴性とともに、ブロッツマンは抒情的でもあり、スウィングもしていたのだった。

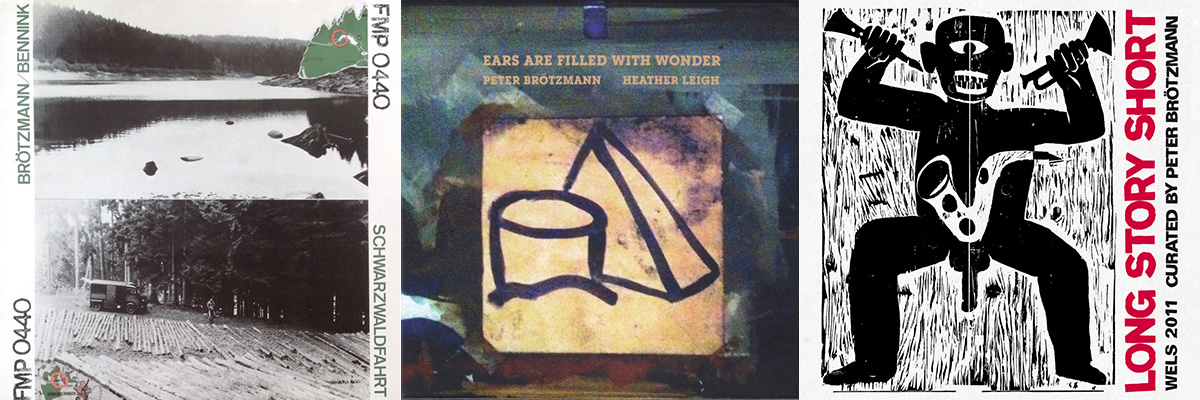

このことは、背景をそぎ落とした場面での方が敏感に察することができるだろう。有名な例としては、1997年にドイツの黒い森にてベニンクと野外で録音した『Schwarzwaldfahrt』があるが、これは彼の生涯のディスコグラフィの中でももっとも探究的で遊び心のあるアルバムのひとつだ。ブロッツマンのキャリアの後期にペダル・スティール・ギタリストのヘザー・リーと結成した意外性のあるデュオも、多くの美しい瞬間を生み出した。彼の訃報に接し、私が最初に手を伸ばしたのは、このデュオにふさわしいタイトルをもつ2016年のアルバム『Ears Are Filled With Wonder(耳は驚きで満たされる)』 で、彼のもっともロマンティックなところが記録されている。

ブロッツマンは、文脈を変えながら、自身の銃(マシン・ガン)に忠実でいるという特技を持ち合わせていた。そのキャリアを通して、1970年代のヴァン・ホーフとベニンクとのトリオから2000年代のシカゴ・テンテットなど、多数のグループを率いたが、目標を達成したと感じるとすぐにそこから手を引いてしまうのが常だった。2011年にオーストリアのヴェルスでのアンリミテッド・フェスティヴァルのキュレーションを担当した際には、当時の彼の活動の範囲の広さが瞬時にわかるような展開だった。彼はシカゴ・テンテット、ヘアリー・ボーンズとフル・ブラストとともに登場するだけでなく、日本のピアニストの佐藤允彦からモロッコのグナワの巨匠、マーレム・モフタール・ガニアまで、ヴァラエティに富んだミュージシャンたちとのグループで演奏した。(このフェスのハイライトは、5枚組のコンピレーション『Long Story Short』 に収録されており、最初から最後まで聴覚が活性化されるような体験ができるだろう)。

ブロッツマンの日本のアーティストたちとのもっとも実りの多い関係が、彼自身と匹敵するぐらい強力なパーソナリティを持つ人たちとのものであったのは、至極当然である。私が思い浮かべるのは、灰野敬二、近藤等則、羽野昌二そして坂田明だ。彼はまた、若い世代のマッツ・グスタフソンやパール・ニルセン=ラヴなど、彼のことを先駆者としてお手本としたミュージシャンたちをスパーリング・パートナーに見出した。セッティングがどうであれ、中途半端は許されなかった。

「ステージに立つというのは、友好的な仕事ではない」と2018年のレッド・ブル・ミュージック・アカデミー・レクチャーで、ブロッツマンは語った。「ステージ上は、たとえ親友と一緒だとしても、闘いの場なのだ。戦って、緊張感を保ち、挑戦し、新しい状況が必要で、それに反応しなくてはならない。それが、音楽を生きたものにするのだと思う」

The indomitable Peter Brötzmannwritten by James Hadfield

For years, Peter Brötzmann’s visits to Japan felt as regular as the seasons, like a late-autumn typhoon rolling through. There was something elemental and earthy about him. It wasn’t just the sound he made – a tempestuous roar that could give way to tender, bluesy caresses – but also his presence. He cut an imposing figure, with his walrus moustache and penchant for cigars, his no-nonsense aura. Brötzmann didn’t take any shit.

The German saxophonist and woodwind player, who died on June 22 at the age of 82, spent much of his career battling against indifference and outright vitriol. As a young man, he scandalised the European jazz establishment with his assaults on traditional notions of harmony and form, pushing even further into the unknown than US contemporaries like Albert Ayler or Pharaoh Sanders. Don Cherry gave him the nickname “machine gun,” which would provide the title for Brötzmann’s 1968 sophomore album, a landmark in the development of free jazz.

Initially released in an edition of just 300 copies on his own BRÖ label, it was an album that captured the explosive atmosphere of the times: the Vietnam War, the mass protests convulsing Europe. Although it featured an international cast of musicians – including Belgian pianist Fred Van Hove, Dutch drummer Han Bennink and British saxophonist Evan Parker – “Machine Gun” also seemed to be taking aim at a specifically German target: the shame and trauma of the country’s Nazi past.

“That’s maybe why the German way of playing this kind of music always sounds a bit different than the music from other parts of Europe,” Brötzmann told Die Zeit, in an interview conducted in early June, just weeks before his death. “It’s always more a kind of scream. More brutal, more aggressive.”

That scream would continue to resound through the decades to come. Whereas many of his free-jazz peers either died young or mellowed with age, Brötzmann kept playing with the same incandescent force. This came at considerable cost to his health: during his final decades, he suffered from respiratory problems that he attributed to a lifetime of overblowing. As he told The Wire in a 2012 interview, “I wanted to sound like four tenor saxophonists... That’s what I was attempting with ‘Machine Gun’ and that’s what I’m still chasing.”

It was a sound that provoked visceral responses. I remember taking an unsuspecting friend to see Brötzmann perform with his group Full Blast at London’s Cafe Oto in 2010, and watching her physically recoil as he started playing.

However, Brötzmann’s reputation as a bruiser was only ever part of the story. A self-taught musician, he had started out playing Dixieland and swing, and he retained a deep love for earlier saxophone pioneers like Coleman Hawkins and Sidney Bechet. These influences are audible even on “Machine Gun”: you can hear the honking tenor of Jean-Baptiste Illinois Jacquet, the hot jazz of early Louis Armstrong. For all his ferocity, Brötzmann was lyrical and swinging too.

This was perhaps easier to appreciate in more stripped-back settings. A notable example is 1977’s “Schwarzwaldfahrt,” recorded al fresco with Bennink in Germany’s Black Forest, and one of the most inquisitive and playful albums in his entire discography. Brötzmann’s late-career duo with pedal steel guitarist Heather Leigh – an unlikely combination – also gave rise to many moments of beauty. When I heard about his passing, the first album I reached for was the duo’s aptly titled 2016 album “Ears Are Filled With Wonder,” which captures him at his most romantic.

Brötzmann had a talent for sticking to his (machine) guns while changing the context. He led many groups during his career, from his 1970s trio with Van Hove and Bennink to his Chicago Tentet during the 2000s, but would typically pull the plug on each of them as soon as he felt they had fulfilled their purpose. When he curated the 2011 edition of the Unlimited festival in Wels, Austria, it provided a snapshot of the extent of his activities at the time. He appeared with the Chicago Tentet, Hairy Bones and Full Blast, but also in a variety of other groupings, with musicians ranging from Japanese pianist Masahiko Satoh to Morocccan gnawa master Maâlem Mokhtar Gania. (Highlights of the festival are compiled on the 5-disc “Long Story Short” compilation, an invigorating listen from start to finish.)

It makes sense that some of Brötzmann’s most fruitful relationships with Japanese artists were with personalities as forceful as his own – I’m thinking of Keiji Haino, Toshinori Kondo, Shoji Hano, Akira Sakata. He also found sparring partners among a younger generation of musicians, such as Mats Gustafsson and Paal Nilssen-Love, who owed much to his trailblazing example. Whatever the setting, there was no excuse for half measures.

“Being on stage is not a friendly business,” he said during a Red Bull Music Academy lecture in 2018. “Being on stage is a fight, even if you stay there with the best friend. But you have to fight... You need tension, you need challenges, you need a new situation, you have to react. And that makes the music alive, I think.”

Profile

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド/James Hadfield

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド/James Hadfieldイギリス生まれ。2002年から日本在住。おもに日本の音楽と映画について書いている。『The Japan Times』、『The Wire』のレギュラー執筆者。

James Hadfield is originally from the U.K., but has been living in Japan since 2002. He writes mainly about Japanese music and cinema, and is a regular contributor to The Japan Times and The Wire (UK).

COLUMNS

- Columns

スティーヴ・アルビニが密かに私の世界を変えた理由 - Columns

6月のジャズ- Jazz in June 2024 - Columns

♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう - Columns

5月のジャズ- Jazz in May 2024 - Columns

E-JIMAと訪れたブリストル記 2024 - Columns

Kamasi Washington- 愛から広がる壮大なるジャズ絵巻 - Columns

♯6:ファッション・リーダーとしてのパティ・スミスとマイルス・デイヴィス - Columns

4月のジャズ- Jazz in April 2024 - Columns

♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く - Columns

3月のジャズ- Jazz in March 2024 - Columns

ジョンへの追悼から自らの出発へと連なる、1971年アリス・コルトレーンの奇跡のライヴ- Alice Coltrane - Columns

♯4:いまになって『情報の歴史21』を読みながら - Columns

攻めの姿勢を見せるスクエアプッシャー- ──4年ぶりの新作『Dostrotime』を聴いて - Columns

2月のジャズ- Jazz in February 2024 - Columns

♯3:ピッチフォーク買収騒ぎについて - Columns

早世のピアニスト、オースティン・ペラルタ生前最後のアルバムが蘇る- ──ここから〈ブレインフィーダー〉のジャズ路線ははじまった - Columns

♯2:誰がために音楽は鳴る - Columns

『男が男を解放するために』刊行記念対談 - Columns

1月のジャズ- Jazz in January 2024 - 音楽学のホットな異論

第2回目:テイラー・スウィフト考 - ――自分の頭で考えることをうながす優しいリマインダー

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE