MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

Home > Columns > CAN:パラレルワールドからの侵入者

映画『イエスタデイ』は、ビートルズのいない世界を想像してみろと、私たちに問いかける。リチャード・カーティスの、代替えの歴史の悪夢のように陳腐なヴィジョンのなかでも、音楽の世界はほとんどいまと変わらないように見え、エド・シーランが世界的な大スターのままだ。

しかし、多元宇宙のどこかには、ロックンロールの草創期にビートルズのイメージからロックの方向性が生まれたのではなく、カンの跡を追うように出現したパラレルワールド(並行世界)が存在するのだ。それは、戦争で爆破された瓦礫から成長した新しいドイツで、初期のロックンロールがファンクや実験的なジャズと交わり、ポピュラー・ミュージックがより流動的で自由で、爆発的な方向性の坩堝となり、アングロ・サクソン文化に独占されていた業界の影響から独立した世界だ。

カンのヴォーカルにマルコム・ムーニーを迎えた初期のいくつかの作品では、このような変化の過程を聴くことができる。アルバム『Delay 1968』の“Little Star of Bethlehem”では、ねじれたビーフハート的なブルース・ロックのこだまが聴こえるし、“Nineteenth Century Man”は数年前にビートルズ自身が“Taxman”で掘り起こしたのと同じリズムのモチーフを使った、拷問のようなテイクをベースにしている。

カンの1969年の公式デビュー盤、『Monster Movie』のクロージング・トラック、“Yoo Doo Right”は、いかにバンドがチャネリングをして、ロックンロールを前進的な思考で広がりのあるものへと変えていったかがわかる小宇宙のようだ。ムーニーのヴォーカルが、「I was blind, but now I see(盲目であった私は、いまは見えるようになった)」や、「You made a believer out of me(あなたのおかげで私は信じることができた)」とチャントして、ロックとソウルの精神的なルーツを呼び覚ますが、それはベーシストのホルガ―・シューカイとドラマーのヤキ・リーベツァイトのチャネリングにより、制約され、簡素化されて、容赦のないメカニカルでリズミカルなループとなり、ミヒャエル・カローリのギターのスクラッチや、渦巻き、切りつけるようなスコールの満引きに引っ張られて、ヴォーカルから焦点がずらされる。

カンが1960年代に取り組んでいたロックの変幻自在の魔術への、もうひとつ別の窓は、映画のための音楽を収録したアルバム『Soundtracks』で見ることができる。クロージング・トラックの “She Brings the Rain” などは、かなり耳馴染みのある1960年代のサイケデリックなロックやポップのようにも聴こえるが、このアルバムでは、それ以外にも何か別のものが醸し出されている。それは “Mother Sky” の宇宙的なギターとミニマルなモータリックの間に編まれた緊張感のあるインタープレイや、ヌルヌルしたグルーヴと新しいヴォーカリスト、ダモ鈴木の “Don’t Turn The Light On, Leave Me Alone” での不明瞭なヴォーカルでより顕著であり、おそらくバンドの最盛期の基礎を築いている。

『Tago Mago』、『Ege Bamyasi』、『Future Days』といったアルバムは、現代のポピュラー・ミュージックの基礎となったカンのパラレルワールドが、我々の世界にもっとも近づいた所にあるものと言えるだろう。目を細めれば、異次元の奇妙な建築物と異界のファッションが、世界の間に引かれたカーテンをすり抜けて侵入しているのが、かろうじて見えるはずだ。それはポスト・パンク・バンドのパブリック・イメージ・リミテッド、ESG、ザ・ポップ・グループ他の生々しい、調子はずれのファンクのリズムや、ざらついたサウンドスケープ、あるいはマッドチェスター・シーンのハッピー・マンデーズやストーン・ローゼスといったバンドのゆるいサイケデリックなグルーヴのなかに、またソニック・ユースとヨ・ラ・テンゴのテクスチュアとノイズのなかに見ることができる。さらに1990年代初期のポスト・ロック・シーンでも、ステレオラブやトータスといったバンドの反復や音の探究を経て、おそらく21世紀でもっとも影響力のあるバンド、レディオヘッドにまで及んだ。カンは過去半世紀にわたり、ポピュラー・ミュージックの進化に憑りついてきた幽霊なのだ。

カンの影響が長いこと残り続けるあらゆる“ポスト〜”のジャンル(ポスト・パンク、ポスト・ロック、そしてかなりの範囲でのポスト・ハードコアも)が、私にとって重要に思えるのは、これらはジャンルを超越したところにある、生来の本能的なジャンルだったからだ。ポスト・パンクは、パンクに扇動されて自滅したイヤー・ゼロ(0年)に、ファンク、ジャズ、ムジーク・コンクレート、プログレッシヴ・ロック他を素材として掘り起こし、自らを再構築しようとしていた音楽だ。一方、ポスト・ロックは生楽器をエレクトロニック・ミュージックの創作過程のループ、オーバーレイやエディットに持ち込んだ。それらは、従来のロック・ミュージックの世界での理解を超えた居心地の悪い音楽的なムーヴメントだったのだ。言うまでもなく、カンは最初からロックの接線上に独自の道を切り開いてきており、マイルス・デイヴィスが自身のジャズのルーツから切り開いた粗っぽいロックンロールのルーツと同じく、予測不可能なジャンルのフュージョンへの地図を描いていた──おそらくカンの爆発的なジャンルを超越した初期のアルバムにもっとも近い同時代の作品は、マイルスが平行探査した『Bitches Brew』 と『On the Corner』などのアルバムだろう。

この雑食性で遊び心に満ちた折衷主義は、鈴木の脱退後のアルバムにおいても、カンの音楽の指針となっていたが、『Tago Mago』で到達した生々しい獰猛さを、1974年の『Soon Over Babaluma』の雰囲気のある、トロピカルにも響くサイケデリアのような控えめな(とはいえ、まったく劣ることのない)ものに変えたのだ。

彼らはもちろん時代の先をいっていた。ロックの純粋主義者たちは、バンドの70年代後半のアルバムに忍び寄るディスコの影響を見て取り、冷笑したかもしれないが、グループの当時のダンス・ミュージックの流行への興味は、カンの幽霊の手(『Out of Reach』のジャケットのイメージによく似ている)に、彼らの宇宙的な次元と、報酬目当てのメインストリーム・ミュージックが独自の行進を続ける世界との間のヴェールを掴ませる役割を果たしていたのだ。カンは一度もロック・バンドであったことはなかったし、シューカイが徐々にベーシストとしての役割からリタイアし、テープ操作に専念するようになったことは、バンドの特異なアプローチが、音楽がやがてとることになる幅広いトレンドの方向性を予見させる多くの方法のひとつであったと言える。もっとも、カン自身はそれらのトレンドに対しては、斜に構え、独自の動きを続けた。

そういった意味では、1979年の自身の名を冠したアルバムは、カンのことを雄弁に物語っている。10年に及ぶキャリアのなかで蒔いた種が、新世代の実験的なマインドを持ったアーティストたちに刈り取られ始め、カンの音楽とアプローチを軸にした作品が創られ始めたため、彼らはそういった作品に、“巨大なスパナを投げつけて”、妨害せずにはいられなかった。カン自身が創ったミニマリストのような、歪んだノイズのアトモスフェリックなディスコと、ファンクに影響されたサウンドは、キャバレー・ヴォルテールやペル・ウブ、ア・サートゥン・レシオなどと並べても違和感がなく、“ A Spectacle” や “ Safe” などのトラックは、彼らの技の達人ぶりを示していた。しかし決して安全な場所には留まらないのがカンであり、デイヴ・ギルモア時代のピンク・フロイド(1979年には絶対クールではなかった)のような世界にも喜んで飛び込み、SIDE2の大部分を躁状態のダジャレの効いたジャック・オッフェンバックの「天国と地獄」のダンスのテーマである“Can-Can(カン・カン)”の脱構築に費やし、間にはピンポン・ゲームまではさんでいる。言うまでもなく、彼らの最もバカバカしく、最高のアルバムのひとつだ。

カンの影響下にあるパラレルワールドは、時に我々の世界の近くにありながら、その音楽はあまりにも多くの迂回路に進むため、ほとんどの場合、ぎりぎり手が届かないというフラストレーションを感じてしまう。我々は、次元の間に引かれたカーテンを完全に通過することはできないかもしれないが、隅々まで目をこらして、影や、我々の世界の亀裂を見ると、そこにまだ特異性が根付いているのを見出すことができる。そこには何かが存在し、他の場所からの侵入者が、我々が引いた線の間をぎこちないファンキーさで滑りこんできて、固体を変異可能にし、現実を異世界にし、異世界を現実にするのだ。

ここに、バンドの面白さを象徴していると思う6枚のアルバムを挙げる。

『Soundtracks』──1960年代のロックから、より宇宙的なものへのバンドの変遷を示している。

『Unlimited Edition』──カンのもっとも折衷主義的で、実験的なアルバム。

『Tago Mago』 ──カンのもっとも極端な状態。

『Ege Bamyasi』──ダモ鈴木時代の、もっとも親しみやすさを実現した作品。

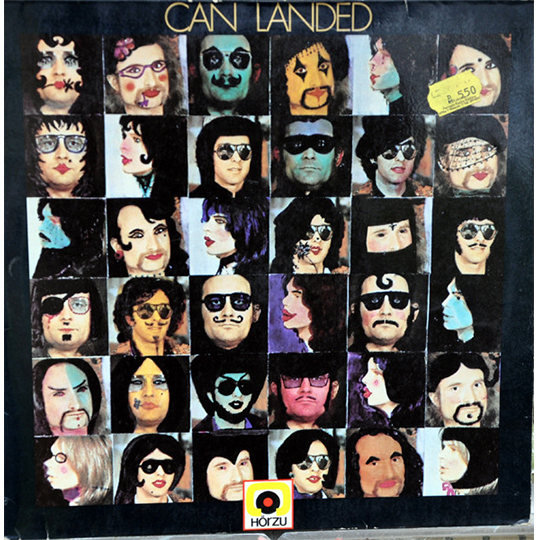

『Landed』──ポップ、エクスペリメンタル、アンビエントなアプローチをミックスするカンの能力を示す素晴らしい一例。

『Can』 ──バンドがバラバラな状態にあっても、常に自分たちにとって心地よいカテゴリーの作品を作るのを避けていたことがわかる。

(7枚目の選択として、『Soon Over Babaluma』は、もっとも繊細で雰囲気のある、カンの一例。)

Can: Intruders from a Parallel World

Ian F. Martin

The movie Yesterday asks us to imagine a world without The Beatles. In Richard Curtis’ nightmarishly banal vision of that alternate history, the music world seems much the same and Ed Sheeran is still a global megastar.

Somewhere in the multiverse, though, there’s a parallel world where the direction of rock emerged out of its rock’n’roll youth not in the image of The Beatles but rather sailing in the wake of Can. It’s a world in which a new Germany, growing from the war’s bombed-out wreckage, was the crucible in which the raw energy of early rock’n’roll merged with funk and experimental jazz, taking popular music in more fluid, free-flowing, explosive directions, independent from the hegemonic influence of the Anglo-Saxon culture industries.

You can hear this process of transformation happening in some of Can’s early work with Malcolm Mooney on vocals. On the album Delay 1968, you can hear warped, Beefheartian echoes of blues rock in Little Star of Bethlehem, while Nineteenth Century Man is based around a tortured take on the same rhythmical motif The Beatles themselves had mined on Taxman a couple of years previously.

On Can’s official debut, 1969’s Monster Movie, the closing track Yoo Doo Right is like a microcosm of how the band were channeling rock’n’roll into something forward-thinking and expansive. Mooney’s vocals summon forth chants of “I was blind, but now I see” and “You made a believer out of me” from the rock and soul’s spiritual roots, but it’s constrained, streamlined and channeled by bassist Holger Czukay and drummer Jaki Liebezeit into a relentless, mechanical rhythmical loop, the vocals dragged in and out of focus by the ebbs and flows of Michael Karoli’s scratching, swirling and slashing squalls of guitar.

A different window into the transformational witchcraft that Can were working on 1960s rock can be seen on the album Soundtracks, which collects some of their work for films. Some songs, like the closing She Brings the Rain, come across as quite familiar sounding 1960s psychedelic rock and pop, and yet something else is brewing in the album too. It’s there most clearly in the tightly wound, tense interplay between cosmic guitars and minimalist motorik rhythms of Mother Sky, as well as more subtly in the slippery grooves and new vocalist Damo Suzuki’s slurred vocals on Don't Turn The Light On, Leave Me Alone, laying the ground for what is probably the band’s most celebrated phase.

The albums Tago Mago, Ege Bamyasi and Future Days are really where that parallel world in which Can were the foundation of modern popular music moves closest to our own. Squint and you can just about see that other dimension’s strange architecture and alien fashions trespassing through the curtain between worlds. You can hear it in raw, discordant funk rhythms and harsh soundscapes of post-punk bands like Public Image Limited, ESG, The Pop Group and others; it’s in the loose, psychedelic grooves of Madchester scene bands like The Happy Mondays and The Stone Roses; it’s in the textures and noise of Sonic Youth and Yo La Tengo; it’s in the repetition and sonic exploration of the nascent 1990s post-rock scene, filtering through bands like Stereolab and Tortoise, eventually informing perhaps the most influential rock band of the 21st Century, Radiohead. Can are a ghost that’s been haunting the evolution of popular music for the past half century.

The lingering influence of Can on all the “post-” genres (post-punk, post-rock and to a large extent post-hardcore too) feels important to me, because these were genres with an innate instinct towards transcending genre. Post-punk was music trying to build itself anew after the year-zero self-destruction instigated by punk, mining fragments of funk, jazz, musique concrète, progressive rock and more as its materials. Meanwhile, post-rock brought the live instruments of rock into the loops, overlays and edits of electronic music’s creation process. They were musical movements uncomfortable in the world of rock music as conventionally understood. Can, needless to say, had been charting their own path on a tangent from rock since the beginning, approaching a similar slippery fusion of genres from the rough roots of rock’n’roll that Miles Davis had been charting from his own jazz roots at the same time — arguably the closest thing to Can’s explosive, genre-transcending early albums among any of their contemporaries can be found in Davis’ parallel explorations on albums like Bitches’ Brew and On the Corner.

That omnivorous, playful eclecticism remained a guiding feature of Can’s music in the albums that followed Suzuki’s departure, even as they traded in the raw ferocity that had reached its peak in Tago Mago for something more understated (but in no way lesser) in the atmospheric and even tropical sounding psychedelia of 1974’s Soon Over Babaluma.

They stayed ahead of the curve too. Rock purists may have sneered at what they saw as a creeping disco influence on the band’s late-70s albums, but the group’s interest in then-contemporary dance music kept Can’s spectral hand (much like the jacket image of Out of Reach) grasping at the veil between their cosmic dimension and the mercenary world where mainstream music continued its own march. Can had never been a rock band anyway, and Czukay’s gradual retirement from bass duties to focus on tape manipulation is another of the many ways the band’s idiosyncratic approach foreshadowed the direction broader trends in music would eventually take, even as Can themselves continued to move oblique to those trends.

In this sense, their self-titled 1979 album says a lot about Can. Just as the seeds sown by their then ten year career were starting to be reaped by a new generation of experimentally minded artists and the pieces were starting to realign themselves around Can’s music and approach, they couldn’t resist throwing a giant spanner in the works. The sort of minimalist, noise-distorted, atmospheric, disco- and funk-influenced sounds Can had made their own would have sat very comfortably alongside the likes of Cabaret Voltaire, Pere Ubu and A Certain Ratio, and in tracks like A Spectacle and Safe, Can showed they were masters of that craft. Can were never about being safe though, and they were just as happy diving down rabbit holes of Dave Gilmour-era Pink Floyd (desperately uncool in 1979) and devoting a large chunk of side 2 to a manic, pun-driven deconstruction of Jacques Offenbach’s “Can-Can” dance theme, interspersed with a game of ping pong. Needless to say, it’s one of their silliest and best albums.

The parallel world that lives under the influence of Can is sometimes tantalisingly close to our own, and yet their music pursues so many oblique detours that it mostly feels frustratingly just out of reach. We may never fully be able to pass through that curtain between dimensions, but look in the corners, the shadows and the cracks in our world where idiosyncrasies can still take root, and there is something there: some trespasser from elsewhere, slipping in their awkwardly funky way between the lines we draw, making the solid mutable, the real otherworldly and the otherworldly real.

Here are 6 albums that I think represent six interesting aspects of the band.

Soundtracks - Shows the band's transition from 1960s rock into something more cosmic.

Unlimited Edition - Can at their most eclectic and experimental.

Tago Mago - Can at their most extreme.

Ege Bamyasi - The most accessible realisation of the Damo Suzuki era.

Landed - A great example of Can's ability to mix pop, experimental and ambient approaches.

Can - Shows how even as the band were falling apart, they always avoided making anything that fit into a comfortable category.

(As a 7th choice, Soon Over Babaluma is a great example of Can at their most subtle and atmospheric.)

Profile

Ian F. Martin

Ian F. MartinAuthor of Quit Your Band! Musical Notes from the Japanese Underground(邦題:バンドやめようぜ!). Born in the UK and now lives in Tokyo where he works as a writer and runs Call And Response Records (callandresponse.tictail.com).

COLUMNS

- Columns

スティーヴ・アルビニが密かに私の世界を変えた理由 - Columns

6月のジャズ- Jazz in June 2024 - Columns

♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう - Columns

5月のジャズ- Jazz in May 2024 - Columns

E-JIMAと訪れたブリストル記 2024 - Columns

Kamasi Washington- 愛から広がる壮大なるジャズ絵巻 - Columns

♯6:ファッション・リーダーとしてのパティ・スミスとマイルス・デイヴィス - Columns

4月のジャズ- Jazz in April 2024 - Columns

♯5:いまブルース・スプリングスティーンを聴く - Columns

3月のジャズ- Jazz in March 2024 - Columns

ジョンへの追悼から自らの出発へと連なる、1971年アリス・コルトレーンの奇跡のライヴ- Alice Coltrane - Columns

♯4:いまになって『情報の歴史21』を読みながら - Columns

攻めの姿勢を見せるスクエアプッシャー- ──4年ぶりの新作『Dostrotime』を聴いて - Columns

2月のジャズ- Jazz in February 2024 - Columns

♯3:ピッチフォーク買収騒ぎについて - Columns

早世のピアニスト、オースティン・ペラルタ生前最後のアルバムが蘇る- ──ここから〈ブレインフィーダー〉のジャズ路線ははじまった - Columns

♯2:誰がために音楽は鳴る - Columns

『男が男を解放するために』刊行記念対談 - Columns

1月のジャズ- Jazz in January 2024 - 音楽学のホットな異論

第2回目:テイラー・スウィフト考 - ――自分の頭で考えることをうながす優しいリマインダー

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE