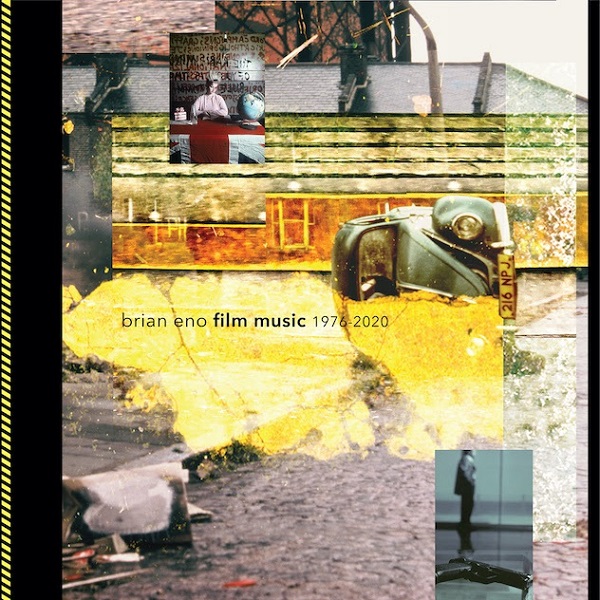

ありそうでなかったブツの登場だ。これまでイーノが手がけてきたサウンドトラックから17曲を選りすぐった編集盤『Film Music 1976 – 2020』が11月13日に発売される(日本盤はユニバーサル ミュージックより)。

イーノはこの50年のあいだに(テレビ含め)数々のサントラを担当してきているが、盤化されていないものも多く、聴く機会に恵まれない音源もそれなりにあった。今回、『トレインスポッティング』の “Deep Blue Day”(昨年リイシューされた『Apollo』収録)やデレク・ジャーマン『セバスチャン』の “Final Sunset”(『Music For Films』収録)などの既発曲も含まれてはいるものの、他方で映画を観ないと(orその映画のDVDを買わないと)聴くことのできなかった音源(デヴィッド・リンチ『デューン』など)もしっかり収録されており、かなり嬉しいリリースとなっている。

発売に先がけ、現在『ラブリーボーン』からジョン・ホプキンス&レオ・エイブラハムスとの共作(『Small Craft On A Milk Sea』の時期の曲ですね)“Ship In A Bottle” が公開中、これも盤化されていなかったトラックだ。

BRIAN ENO

初のサウンドトラック・コレクション・アルバム

リリース決定!

ブライアン・イーノによるサウンドトラック作品を集めた初のコレクション・アルバム『フィルム・ミュージック 1976-2020』が11月13日に発売!

過去50年間でイーノが作ってきた有名曲から、知る人ぞ知る隠れた名曲まで全17曲を収録しており、そのうちの7曲は未発売音源。

CDのほか、2枚組LP(輸入盤のみ)、ダウンロード、ストリーミングのフォーマットで発売。

未発売曲 “シップ・イン・ア・ボトル”(『ラブリーボーン』2009年/監督ピーター・ジャクソンより)が先行配信中。

フィルム・ミュージック 1976-2020

Film Music 1976 – 2020

発売日:2020年11月13日

品番:UICY-15945

価格:2,500円+税

日本盤のみ解説付

UNIVERSAL MUSIC STORE 限定特典:A2サイズ・ポスター ※無くなり次第終了

▼予約・試聴はこちら

https://umj.lnk.to/brian-eno-filmmusic

【収録曲】

01. トップボーイ(テーマ)

『トップボーイ:サマーハウス – シーズン1』(2011年/監督ヤン・ドマンジュ)より

‘Top Boy (Theme)’ from ‘Top Boy’ – Series 1, directed by Yann Demange, 2011

02. シップ・イン・ア・ボトル

『ラブリーボーン』(2009年/監督ピーター・ジャクソン)より

‘Ship In A Bottle’ from ‘The Lovely Bones’, directed by Peter Jackson, 2009

03. ブラッド・レッド

『フランシス・ベーコン 出来事と偶然のための媒体』(2005年/監督アダム・ロウ)より

‘Blood Red’ from ‘Francis Bacon’s Arena’, directed by Adam Low, 2005

04. アンダー

『クール・ワールド』(1992年/監督ラルフ・バクシ)より

‘Under’ from ‘Cool World’, directed by Ralph Bakshi, 1992

05. ディクライン・アンド・フォール

『O Nome da Morte’』(2017年/監督エンリケ・ゴールドマン)より

‘Decline And Fall’ from ‘O Nome da Morte’, directed by Henrique Goldman, 2017

06. 予言のテーマ

『デューン/砂の惑星』(1984年/監督デヴィッド・リンチ)より

‘Prophecy Theme’ from ‘Dune’, directed by David Lynch, 1984

07. リーズナブル・クエスチョン

『We Are As Gods』(2020年/デヴィッド・アルバラード、 ジェイソン・サスバーグ)より

‘Reasonable Question’ from ‘We Are As Gods’, directed by David Alvarado / Jason Sussberg, 2020

08. レイト・イブニング・イン・ジャージー

『ヒート』(1995年/監督マイケル・マン)より

‘Late Evening In Jersey’ from ‘Heat’, directed by Michael Mann, 1995

09. ビーチ・シークエンス

『愛のめぐりあい』(1995年/監督ミケランジェロ・アントニオーニ)

‘Beach Sequence’ from ‘Beyond The Clouds’, directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, 1995

10. ユー・ドント・ミス・ユア・ウォーター

『愛されちゃって、マフィア』(1988年/監督ジョナサン・デミ)より

‘You Don’t Miss Your Water’ from ‘Married to the Mob’, directed by Jonathan Demme, 1988

11. ディープ・ブルー・デイ

『トレインスポッティング』(1996年/監督ダニー・ボイル)より

‘Deep Blue Day’ from ‘Trainspotting’, directed by Danny Boyle, 1996

12. ソンブル

『トップボーイ:サマーハウス – シーズン2』(2013年/監督ジョナサン・バン・トゥレケン)

‘The Sombre’ from ‘Top Boy’ – Series 2, directed by Jonathan van Tulleken, 2013

13. ドーバー・ビーチ

『ジュビリー/聖なる年』(1978年/監督デレク・ジャーマン)より

‘Dover Beach’ from ‘Jubilee’, directed by Derek Jarman, 1978

14. デザイン・アズ・リダクション

『ラムズ』(2018年/監督ゲイリー・ハスウィット)より

‘Design as Reduction’ from ‘Rams’, directed by Gary Hustwit, 2018

15. アンダーシー・ステップス

『ハンマーヘッド』(2004年/監督ジョージ・チャン)より

‘Undersea Steps’ from ‘Hammerhead’, directed by George Chan, 2004

16. ファイナル・サンセット

『セバスチャン』(1976年/監督デレク・ジャーマン)より

‘Final Sunset’ from ‘Sebastiane’, directed by Derek Jarman, 1976

17. アン・エンディング

『宇宙へのフロンティア』(1989年/監督アル・レイナート)より

‘An Ending (Ascent)’, from ‘For All Mankind’, directed by Al Reinert, 1989

イーノが手掛けた曲は、今までに、映画や、ドキュメンタリー、テレビなどで何百曲と使用されてきた。また、世界的にも有名な監督の元で全編を通してのサウンドトラックを20作品以上手がけている。今回の『フィルム・ミュージック 1976-2020』は、イーノの最も著名な映画およびテレビのサウンドトラック17曲を収録した待望の1枚となっており、イーノの膨大な作品群への究極の入門書でもある。

イーノの長年に亘る映画との関わりは、1970年にマルコム・レグライス監督の実験的な短編映画『Berlin Horse』のサウンドトラックを手がけたことがきっかけだった。1976年には、『セバスチャン』と、長く忘れられていたギリシャのB級ホラー映画で『The Devil’s Men』という別名でも知られている『デビルズ・ビレッジ 魔神のいけにえ』でもサウンドトラックを手がけ、その後、自身のアルバムである『ミュージック・フォー・フィルムズ』をきっかけにさらに精力的に映画音楽に取り組んだ。

初期のイーノによる映画音楽の代表曲は、デヴィッド・リンチ監督『デューン/砂の惑星』からの「予言のテーマ」、マイケル・マン監督『ヒート』からの「Late Evening In Jersey」、ラルフ・バクシ監督『クール・ワールド』からの「Under」、そして、ジョナサン・デミ監督『愛されちゃってマフィア』で、ウィリアム・ベルのソウル・クラシックを情感たっぷりにカヴァーした「You Don’t Miss Your Water」などがあげられ、今作に収録されている。