クルアンビンのサード・アルバム『モルデカイ』のリミックス盤が8月6日に出ます。タイトルは『MORDECHAI REMIXES(モルデカイ・リミクシーズ)』。これが予想通りの気持ちよさ。ハウシーで、トライバルで、ときにダビーで。まさにsoud of summerの1枚です。ためしに1曲聴いてみましょう。

Khruangbin - Pelota (Cut a Rug Mix) - Quantic Remix

全リミキサーは以下の通り。

Kadhja Bonet(LAの女性シンガー/マルチインストゥルメンタリスト)、Ginger Root(カリフォルニア出身のインディ・ロッカー)、Knxwledge(LAのプロデューサー/ビートメーカー)、Natasha Diggs(NYをベースとするDJ/プロデューサー)、Soul Clap(マサチューセッツ州ボストン出身のモダン・ハウスDJデュオ)、Quantic(イギリスのDJ/プロデューサー)、Felix Dickinson(UKアンダーグラウンド・ダンス・シーンの実力者)、Ron Trent(シカゴ・ハウスのレジェンド)、Mang Dynasty(UKディスコ・シーンを代表するDJ/プロデューサー/リミキサー、Ray Mangとイギリスの作家/ディスクジョッキー、Bill Brewsterによるユニット)、Harvey Sutherland(メルボルンのクラブミュージックシーンで注目を集めるアーティスト)

2021年8月6日にデジタル、10月29日にLPでリリース。CDは日本のみでのリリース。

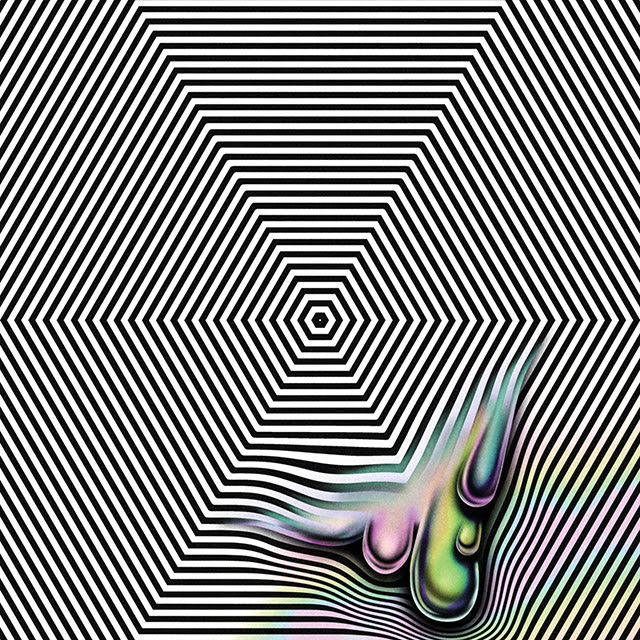

KHRUANGBIN(クルアンビン)

MORDECHAI REMIXES(モルデカイ・リミクシーズ)

ビッグ・ナッシング/ウルトラ・ヴァイヴ

■収録曲目:

1. Father Bird, Mother Bird (Sunbirds) (Kadhja Bonet Remix)

2. Connaissais De Face (Tiger?) (Ginger Root Remix)

3. Dearest Alfred (Myjoy) (Knxwledge Remix)

4. First Class (Soul In The Horn Remix) (Natasha Diggs Remix)

5. If There Is No Question (Soul Clap Wild, but not Crazy Mix) (Soul Clap Remix)

6. Pelota (Cut A Rug Mix) (Quantic Remix)

7. Time (You and I) (Put a Smile on DJ's Face Mix) (Felix Dickinson Remix)

8. Shida (Bella's Suite) (Ron Trent Remix)

9. So We Won’t Forget (Mang Dynasty Version) (Mang Dynasty Remix)

10. One to Remember (Forget Me Nots Dub) (Harvey Sutherland Remix)