MOST READ

- interview with xiexie オルタナティヴ・ロック・バンド、xiexie(シエシエ)が実現する夢物語

- Chip Wickham ──UKジャズ・シーンを支えるひとり、チップ・ウィッカムの日本独自企画盤が登場

- Natalie Beridze - Of Which One Knows | ナタリー・ベリツェ

- 『アンビエントへ、レアグルーヴからの回答』

- interview with Martin Terefe (London Brew) 『ビッチェズ・ブリュー』50周年を祝福するセッション | シャバカ・ハッチングス、ヌバイア・ガルシアら12名による白熱の再解釈

- VINYL GOES AROUND PRESSING ──国内4か所目となるアナログ・レコード・プレス工場が本格稼働、受注・生産を開始

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head / Loula Yorke - Volta | ルーラ・ヨーク

- interview with Chip Wickham いかにも英国的なモダン・ジャズの労作 | サックス/フルート奏者チップ・ウィッカム、インタヴュー

- interview with salute ハウス・ミュージックはどんどん大きくなる | サルート、インタヴュー

- Kim Gordon and YoshimiO Duo ──キム・ゴードンとYoshimiOによるデュオ・ライヴが実現、山本精一も出演

- Actress - Statik | アクトレス

- Cornelius 30th Anniversary Set - @東京ガーデンシアター

- 小山田米呂

- R.I.P. Damo Suzuki 追悼:ダモ鈴木

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant | ブラック・ディセレラント

- Columns ♯7:雨降りだから(プリンスと)Pファンクでも勉強しよう

- Columns 6月のジャズ Jazz in June 2024

- Terry Riley ——テリー・ライリーの名作「In C」、誕生60年を迎え15年ぶりに演奏

- Mighty Ryeders ──レアグルーヴ史に名高いマイティ・ライダース、オリジナル7インチの発売を記念したTシャツが登場

- Adrian Sherwood presents Dub Sessions 2024 いつまでも見れると思うな、御大ホレス・アンディと偉大なるクリエイション・レベル、エイドリアン・シャーウッドが集結するダブの最強ナイト

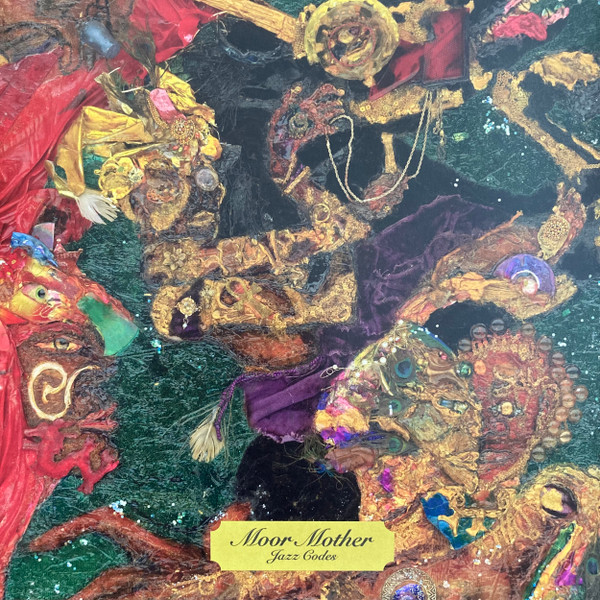

Home > Reviews > Album Reviews > Moor Mother- Jazz Codes

1960年代後半から1970年代初頭にかけて、ドラマーのアーサー・テイラーは、当時を代表するジャズ・ミュージシャンたちにインタヴューを行い、後に著書『Notes and Tones』にまとめた。ジャズが商業的な影響力を失いはじめた時代を捉え、シーンにおける政治的な力学から、当時は「フリーダム・ミュージック」と呼ばれていた音楽の様式的な刷新に至るまでのさまざまな議論が交わされているわけだが、なかでももっとも論争を引き起こしたのは、ジャズという言葉そのもので、アート・ブレイキーがたいした問題ではないと主張した一方、マックス・ローチなどはニューオーリンズの売春宿を起源とし、文脈によっては“クソ”と同義的に使われることもある言葉を自分たちの音楽に押し付けられたことに不快感を示した。ニーナ・シモンはこの問いかけに異なる角度からアプローチし、テイラーに「ジャズはただ音楽であるというだけでなく、生き様であり、在り方であり、物の考え方。それは、アフロ・アメリカ系の黒人を定義するものだ」と語った。

『Jazz Codes』を聴きながら、私はこのことを思い出した。ムーア・マザーの最新ソロ・アルバムは、亡き詩人アミリ・バラカの精神にのっとって、過去と現在(彼女の言うところの「パッド(メモ帳)とペンで瞑想する)」のジャズ・ミュージシャンたちのリズムをリフにすると同時に、音楽を埋め込まれた記憶や奥深い真実として、異界の領域への入り口のように扱っている。2020年の『Circuit City』では、「タイムトラベルや 内外の次元を追求することは不可能/フリー・ジャズなしには」と宣言している。また、アルバムと同じぐらいの長さのビリー・ウッズとのコラボレーション作「Brass」では、「ブルースは、国が忘れてしまった全てのことを覚えている」と注目曲のひとつで書いている。

『Jazz Codes』では、ムーア・マザーの最近のソロ・ミュージックの瑞々しさというトレンドが引き継がれ、2020年のロックダウン時にリリースされた『Clepsydra』や『ANTHOLOGIA 01』、そして昨年の『Black Encyclopedia of the Air』で紡いだ糸を繋いでいる。彼女は再びスウェーデンのプロデューサーでインストゥルメンタリストのオロフ・メランダーと組み、ある種の明晰夢の状態にあるイリュージョン(幻影)と暗示の音楽を呼び起こしている。いくつかの曲は小品に過ぎないが、これらは人を酔わせる、宇宙的な作品だ。

いちばん長く、人を惑わせるような“Meditation Rag”では、サン・ラからジェリー・ロール・モートン、フィスク・ジュビリー・シンガーズといったアーティストの名前を挙げながら、そのまわりをアリャ・アル=スルターニのソプラノのヴォーカルが分散する光のように浮遊し、まるで降霊術の会の様相を呈している。他では、ジェイソン・モラン、メアリー・ラティモアにアイワのインリヴァーシブル・エンタングルメンツのバンド仲間がインストゥルメンタルで貢献し、R&Bヴォーカルのフックやサイケデリックな煌めきや、不明瞭なトリップ・ホップのリズムを紡ぐ。コラボレーションの多いこのようなアルバム制作では、あえてフォアグラウンド(前景)とバックグラウンドを分けていない事が多く、重なり合うヴォイスのなかからリスナー自身が、どれに焦点を当てて聴くのかを選ぶことを任される。

クロージング・トラック“Thomas Stanley Jazzcodes Outro”では、作家でアーティストのトマス・スタンリーがテイラーの著書のテーマを拾い上げている。

多くの評者たちが

ジャズはかつてセックスを意味したと言っている

そしておそらく、

ジャズはセックスを意味するものに

戻る必要があるだろう

性行為や交尾、

ハイパー・クリエイティヴィティ、

繁殖力、

そして誕生と同一視されるように。

『Jazz Codes』の気だるいグルーヴは、アイワがイリヴァーシブル・エンタングルメンツとともに披露する扇情的なフリー・ジャズとは別世界のように思えるが、どちらも音楽が解放の源となり得るという鋭い認識を共有している。

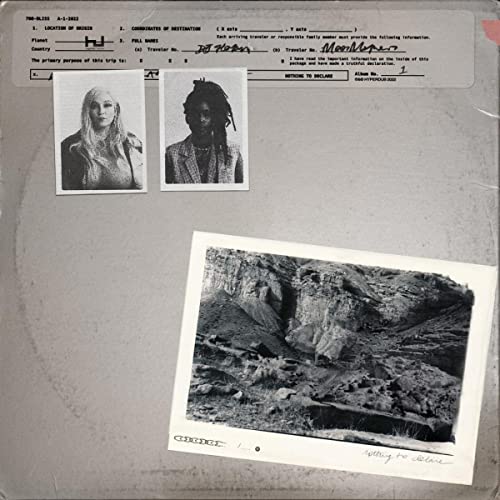

それはまた、彼女と同じフィラデルフィア在住のDJハラムとのデュオ、700 Blissの『Nothing To Declare』でもときどき響いている。このアルバムは、ムーア・マザーの作品のなかでも、2016年の『Fetish Bones』に代表されるようなより挑戦的な側面が好きなファンには即座に魅力的に映るだろうが、ここではサウンドと怒りがある種の無頓着なユーモアのセンスによって抑制されている。

とくにアルバムの前半は、〈Hyperdub〉レーベル・メイトのアヤ(ピッチシフトを好む傾向を含めて)と共通する何かがあり、後半ではクラブから遠くへ離れ、ときには毒気の少ないファルマコンにも似た趣となる。アイワの歌詞は徹底的にルーズで、歌うような韻と言葉のフィジカリティを楽しんでいるように聞こえる。“Bless Grips”で彼女がデス・グリップスのフロントマン、MCライドのリズムを真似る様子をチェックしてほしい。まるでコメディの寸劇のような“Easyjet”では、700 Blissをあきれ顔で批判する二人組をデュオが演じている(おいおい、これはそもそも音楽と言えるのか?)

しかし、より深いところまで切り込んでいるのは、傑出した曲たちだ。“Capitol”でのアイワの冒頭のヴァースは、血で書かれた一般教書演説で(夢の成分をすすりたい/私たちを奴隷にした奴らの喉を切り裂きたい)、何時間でも没頭できる。ほぼインダストリアル・テクノのような“Anthology”では、20世紀半ばに人類学に基ずき振付を芸術に変えた〝ラック・ダンスの女家長〟として活躍したキャサリン・ダナムにオマージュを捧げている。

さらに、数年前にリリースされた“Sixteen”は、このデュオのこれまでの最高傑作といえるかもしれない。アイワは、「もう戯言にはうんざりだ、世界はとても暴力的だ/自分だけの島が欲しい。でも奴らが気候を破壊した」と激しく非難し、ダンスフロアに自らを解き放つ前に「私はただ踊って汗をかきたい/踊って忘れてしまいたいだけ」と歌う。それは、世界がどれほどひどい場所かというのを無視することではなく、生き残るためのツールを見つけることだ。それは音楽であるというだけでなく、生き様や物の考え方のひとつなのだから。

by James Hadfield

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the drummer Arthur Taylor conducted a series of interviews with some of the day’s leading jazz musicians, later collected in his book “Notes and Tones.” It captured a period when jazz was losing its commercial clout, while debates raged over topics from scene politics to the stylistic innovations of what was then still called “freedom music.” But one of the most contentious issues was the word itself: jazz. While Art Blakey insisted it was no big deal, others, such as Max Roach, were upset that their music had been lumbered with a term that originated in the brothels of New Orleans, and in some contexts could be used interchangeably with “shit.”

Nina Simone approached the question from a different angle. “Jazz is not just music, it’s a way of life, it’s a way of being, a way of thinking,” she told Taylor. “It’s the definition of the Afro-American black.”

I was reminded of this while listening to “Jazz Codes.” Moor Mother’s latest solo album finds her working in the spirit of the late poet Amiri Baraka, riffing on the rhythms of jazz musicians past and present (“meditatin′ with the pad and the pen,” as she puts it), but also treating the music as a source of embedded memories and deeper truths—a portal to other realms. As she declared on 2020’s “Circuit City”: “You can’t time travel / Seek inner and outer dimensions / Without free jazz.” Or, in the words of one of the standout tracks from “BRASS,” her album-length collaboration with billy woods: “The blues remembers everything the country forgot.”

“Jazz Codes” continues the recent trend in Moor Mother’s solo music towards lushness, picking up the thread from her 2020 lockdown releases “Clepsydra” and “ANTHOLOGIA 01,” and last year’s “Black Encyclopedia of the Air.” Once again, she works with Swedish producer and instrumentalist Olof Melander to conjure a sort of lucid-dream state: a music of illusions and allusions. Even though some of the tracks are barely more than vignettes, this is heady, cosmic stuff.

On “Meditation Rag,” one of the longest and most transporting songs, she seems to be staging a seance, name-checking artists from Sun Ra to Jelly Roll Morton to the Fisk Jubilee Singers as the soprano vocals of Alya Al-Sultani float spectrally around her. Elsewhere, instrumental contributions—including by Jason Moran, Mary Lattimore and Ayewa’s bandmates from Irreversible Entanglements—weave together with R&B vocal hooks, psychedelic shimmer and slurred trip-hop rhythms. In an album heavy on collaborations, the production often doesn’t distinguish between foreground and background, leaving listeners to decide which of the overlapping voices to focus on.

On the closing track, “Thomas Stanley Jazzcodes Outro,” author and artist Thomas Stanley picks up on a theme from Taylor’s book:

“Many observers have told us that jazz used to mean sex

And maybe it needs to go back to meaning sex:

To being identified with coitus and copulation,

Hyper-creativity, fecundity and birth.”

Although the languid grooves of “Jazz Codes” may seem a world apart from the incendiary free-jazz that Ayewa serves up with Irreversible Entanglements, both share a keen awareness of how music can be a source of liberation.

That’s echoed occasionally on “Nothing to Declare” by 700 Bliss, her duo with fellow Philadelphia resident DJ Haram. It’s an album that will instantly appeal to fans of the more confrontational side of Moor Mother’s work, typified by 2016’s “Fetish Bones,” though here the sound and fury is tempered by an insouciant sense of humour.

Especially during its first half, the album has something in common with Hyperdub label-mate Aya (including a penchant for pitch-shifted vocals); later on, it drifts further from the club, at times resembling a slightly less bilious Pharmakon. On many of the tracks, Ayewa’s lyrics sound downright loose, happy to delight in sing-song rhymes and the physicality of words; check the way she seems to mimic the cadences of Death Grips frontman MC Ride on “Bless Grips.” There’s even a comedy skit, “Easyjet,” in which the duo play a pair of eye-rolling naysayers talking smack about 700 Bliss (“I mean, come on, is this even music?”).

However, the standout tracks are the ones that cut a little deeper. You could spend hours picking apart Ayewa’s opening verse in “Capitol,” a state-of-the-nation address written in blood (“I wanna sip what dreams are made of / I wanna slice the throat of those who enslaved us”). On “Anthology”—over a track that’s practically industrial techno—she pays tribute to Katherine Dunham, the “matriarch of Black dance,” whose pioneering anthropology transformed artistic choreography during the mid-20th century.

Then there’s “Sixteen,” first released a couple of years ago, which may just be the best thing the duo has done so far. “I'm tired of the bullshit, the world's so violеnt / I just want my own island, but they destroyed thе climate,” Ayewa declaims, before finding her release on the dancefloor: “I just wanna dance and sweat / I just wanna dance and forget.” It’s not about ignoring what a fucked-up place the world is, but finding the tools to survive. It’s not just about the music: it’s a way of being, a way of thinking.

ジェイムズ・ハッドフィールド

ALBUM REVIEWS

- Loula Yorke - speak, thou vast and venerable head/ Loula Yorke - Volta

- Actress - Statik

- Black Decelerant - Reflections Vol 2: Black Decelerant

- High Llamas - Hey Panda

- The Stalin - Fish Inn - 40th Anniversary Edition -

- KRM & KMRU - Disconnect

- Cornelius - Ethereal Essence

- Kronos Quartet & Friends Meet Sun Ra - Outer Spaceways Incorporated

- Martha Skye Murphy - Um

- Mouchoir Étanche - Le Jazz Homme

- Taylor Deupree - Sti.ll

- John Cale - POPtical Illusion

- Amen Dunes - Death Jokes

- A. G. Cook - Britpop

- James Hoff - Shadows Lifted from Invisible Hands

DOMMUNE

DOMMUNE