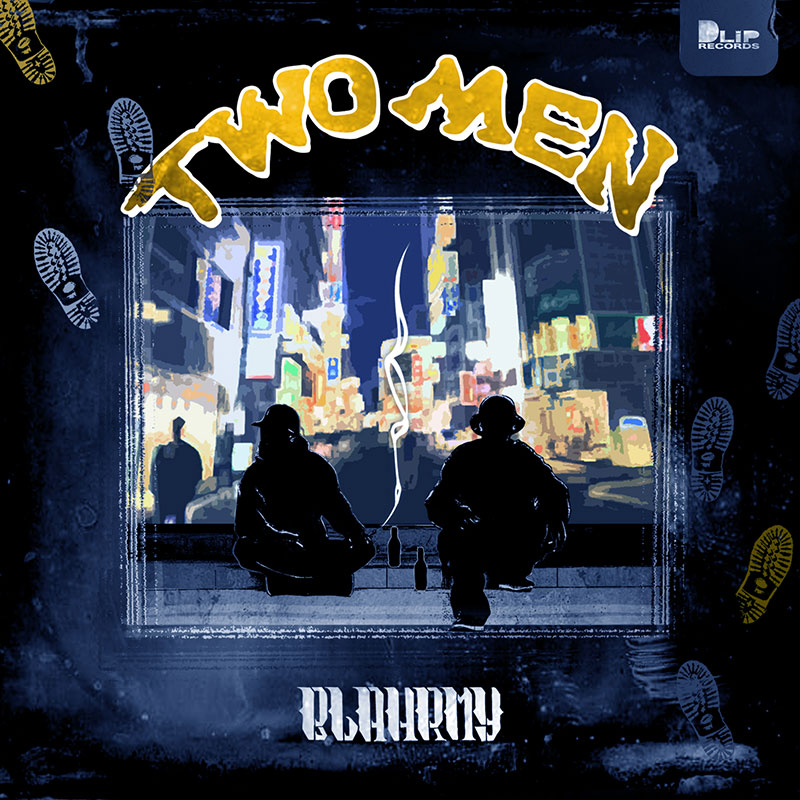

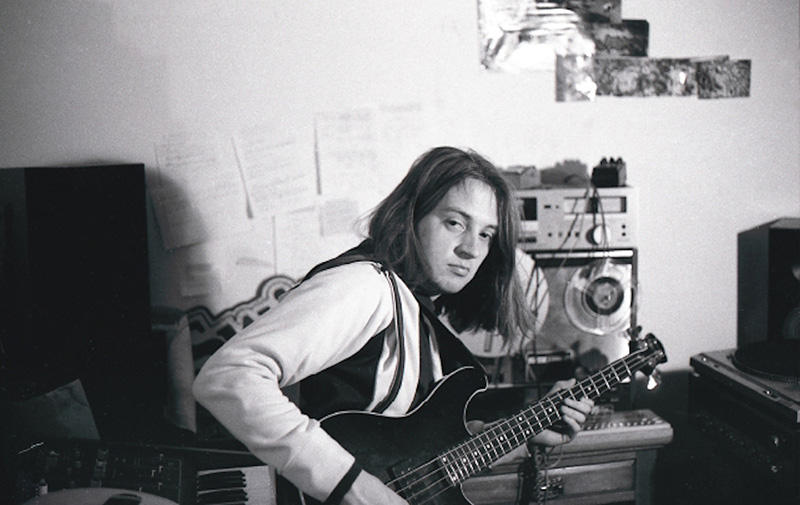

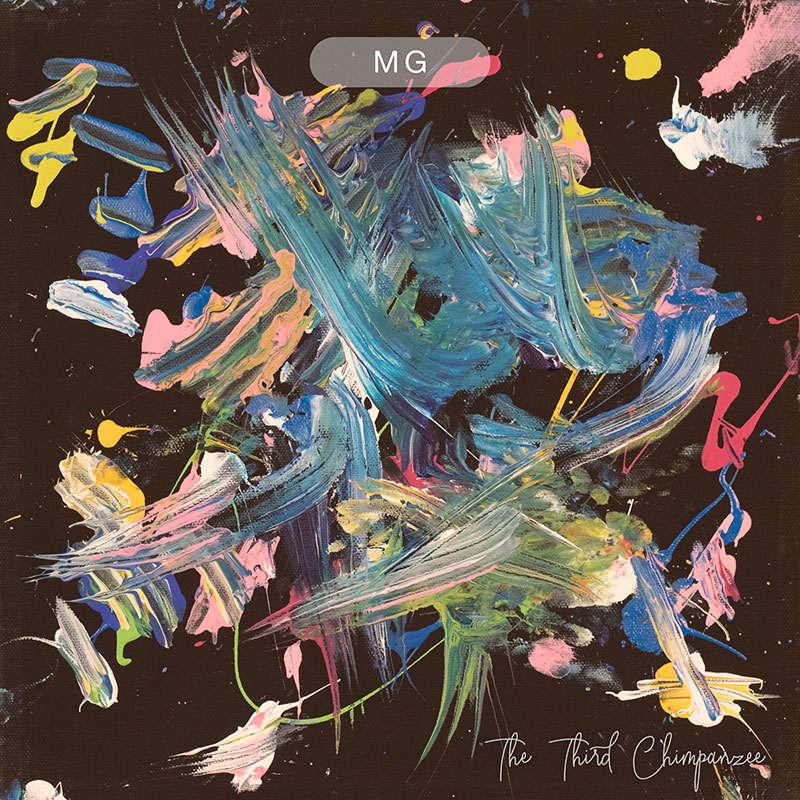

このLPは、れっきとしたハウス・ミュージックだ。しかし正直に告白すると、僕はこの素晴らしいハウスをしかるべき場所──クラブ、あるいはサウンドシステムの整った場所──で聴いて知ったわけではない。ロンドンを拠点とするローレンス・ガイなる青年による、このモダンなディープ・ハウスとは、僕の自宅にあるラップトップで、もっとこまかく言うと YouTube のレコメンドによって出会った。ダンス・ミュージックという点において、その出会いはしかるべき場所ではなかったかもしれないが、ヴァイナルのラベルを映した、ちいさな四角いサムネイルとのファースト・コンタクトが、僕には妙にフィットするように感じられたのだ。

今回、ジャジー~ディープ・ハウスを中心にリリースを手がける〈Church〉からリプレスされた『Saw You For The First Time』は、インターネット・フレンドリーなハウス・ミュージックと言える。DJボーリングの “Winona” を代表例に、数年前のインターネットではLo-Fi ハウスのラベルを後付けしたものが数多く消費され、そこには胸に残らないものもたくさんあったわけだが、それでも抜きん出た才能がいくつか発見され、彼らのキャリアをブーストした。それがDJボーリングであり、DJサインフェルドであり、モール・グラブであり、ロス・フロム・フレンズであり、そのなかでも、特に注目すべき人物が、ローレンス・ガイなのだ。

〈Church〉からすでに2作のEPをリリースしており、満を持してドロップされた今作は、それら一連のEPと地続きの感覚を有したディープ・ハウスに仕上がっているが、決して焼き回しではない。ハウスのDJ・プロデューサーがLPをリリースし、「EPだと調子が良かったけど、LPになるとテンションが続かないな……」と感じることはまれにあるが、今作は10曲入り48分というベストな長さを見つけ、オープナーの “Intro” からクローザーの “W.L.Y.B” まで、見事にテンションを持続させている。低域のしっかりとした四つ打ちはそこにあるものの、ときおり立ち現れるサックスの音色、シンプルなピアノのループ、細切れになったヴォーカル・サンプル、それらが作品全体に大気的な雰囲気を与えており、どこかアンビエントのような感じもある。また、〈Church〉はジャジー・ハウスのイメージが強いから、この作品からもジャズを見出そうとしてしまうが、あくまでそれはムードであり、全体に通底しているのは、やはり繊細で音響的なディープ・ハウスだ。

また、余談ではあるのだが、ジャケットのアートワークがどことなく、ドイツはハンブルクの〈Smallville〉のヴィジュアルに似ているのは偶然だろうか。こちらはディープ・ハウスのレーベルであり、〈Smallville〉がお気に入りなら、ローレンス・ガイによる今作も間違いなくマッチするだろうから、ぜひチェックしてほしい。

こまかく見ていこう。“Gone” は〈Rhythm Section International〉のリリースでも知られるコントゥアーズを招聘し、今作随一のファンクネスを感じるベースと、ピアノによる見事なコンビネーションを披露し、また、スティーヴ・セパセックを客演に迎えた “Drum Is A Woman” では、ピッチベンドをうまく利用した音響的なヴォーカル・プロダクションに仕上げている。もちろん、レーベルメイトであり、ジャズ奏者のイシュマエルによるサックスが冴えわたる “Anchor” も外せない。そして、このLPでの白眉は、間違いなくタイトル・トラックの “Saw You For The First Time” だ。シンプルな四つ打ちから、ピアノのフィルターを変化させながらだんだんと展開していく鉄板のメソッド。エスター・フィリップスによる “A Beautiful Friendship” をサンプリングしており、細切れにされたヴォーカルが、いまにも消え入りそうな声かのごとく操作され、メランコリックな感覚さえ催させる、このLPのハイライトを演出。ローレンス・ガイは賛否両論のあるサンプリングという手法をアートだとみなしており、それについて、カニエ・ウェストやドレイクといったヒップホップ・スターの仕事を賞賛しているが、彼も今作、とりわけこの曲において、サンプリング・ミュージックとして見事な仕事を成し遂げたようだ。

今作は、Lo-Fi ハウスなどというラベルをゆうに超えて、たくさんのひとに聴かれるべき音楽だ。いまにも消えてなくなってしまいそうなアンビエントと、体を内側から刺激するディープなハウスが同居しており、ここには悲しさも暖かさも、両方あるような気がする。2021年現在、YouTube で(期せずして?)Lo-Fi ハウスの旗振り役のひとつとなった〈Slav〉というチャンネルでは、“Saw You For The First Time” の再生回数が200万回を超えている。数字は本質ではないが、参考にはなる。言葉を持たないアンダーグランドな音楽がいまや、インターネットによってこれだけのひとにリーチしているのだ。